Calvin Royal III sensed that Touché, the first homoerotic male pas de deux produced by American Ballet Theatre, would elicit an unusual reaction even before he finished dancing. Audience members generally rustle their programs and shift in their seats when performers are onstage. But on that late October evening inside Lincoln Center in 2021, “it was so quiet,” he remembers. “Absolute silence.” New York City–based ABT is widely considered the most prestigious classical ballet company in the country—and among the most conservative. Its repertoire features classics like Swan Lake and The Nutcracker, rife with tutus and sumptuous sets.

Touché, in contrast, began with Royal and fellow dancer João Menegussi standing against a blank canvas, dressed in street clothes, staring into each other’s eyes. The unspoken tension slowly dissipated, and they embraced, spinning across the stage. Then, the lights went on, and they stumbled away from the spotlight. The theme was unmistakable: Two men were coming to terms with their desire for one another, all the while fearing the stigma attached to gay love. “You could feel people lean into the work,” Royal says. It ended with the men on the floor, shed of most of their clothes, locked in a kiss.

The dancers and choreographer Christopher Rudd knew they had created a combustible piece, but they didn’t know if it would find favor with ABT’s audience. “It’s Lincoln Center,” Royal points out—the definition of the artistic establishment. They need not have worried: It earned a standing ovation, provoking so many curtain calls that Royal lost count. Certainly part of the shake-the-rafters reception was due to the fact that the piece was featured on ABT’s first official Pride Night, but Royal believes it touched a nerve with people irrespective of their sexuality. “We’ve all experienced what it is like to be afraid of something in ourselves,” he says. “What if we were given the opportunity to go after something that we’ve never been able to fully express or verbalize?”

That week, Royal—who is 33—didn’t just dance a piece intricately tied to his experience as a gay man. He also celebrated his performance onstage as a principal dancer for ABT, the first Black man given that title in nearly two decades and only the fourth Black dancer to be promoted to that rank at the company. Days before ABT’s Pride Night, he played Albrecht in Giselle, one of the iconic ballet roles, the equivalent of an actor being tapped for Hamlet.

Christopher Charles McDaniel, a dancer with Dance Theatre of Harlem, took to Instagram to describe how he’d spent most of the matinee in the audience in tears. “I was an eight-year-old all over again, seeing ballet and saying, ‘I want to do this!’” he wrote. “Calvin’s presence reminded me of Arthur Mitchell”—his company’s founder—“telling me I don’t have to be or look ‘classical’ but I can be classic and unique.”

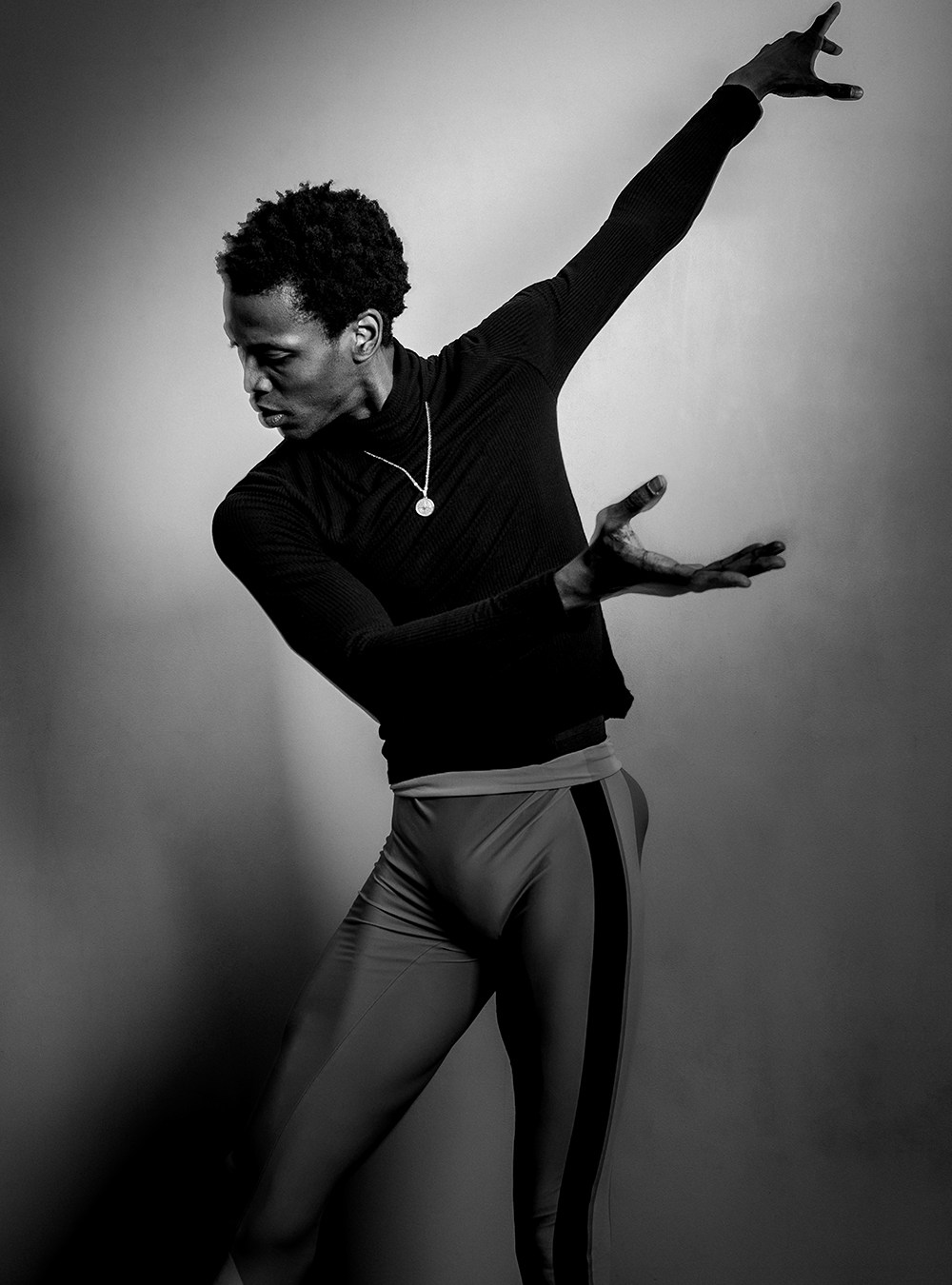

Calvin Royal rehearses with ABT principal Hee Seo.

Malike Sidibe

The art form dates back to the Italian Renaissance, and most classical ballet companies are still overwhelmingly white. Royal’s presence paired with his extraordinary talent are helping to expand conceptions of who can stand center stage. He aspires to do more than that, however. He wants to extend the boundaries of ballet so that it speaks to today’s most pressing issues: “We have to break ballet out of the 18th century.”

In the ABT studios in Manhattan in mid-February, Alonzo King, the founder and artistic director of Lines Ballet company, carefully studied Royal, clad in a T-shirt festooned with the line “Use your power to empower.” Royal was entwined with dancer Katherine Williams; King told her to push back against Royal as they moved in a circle, their muscles visibly flexing. “It’s like he weighs 5,000 pounds,” he told her. “Think of machinery.”

King, an internationally renowned choreographer and ballet master, is one of four Black artists to have created a bespoke piece for ABT in the past two years, after a two-decade period in which no Black Americans choreographed for the company. That’s not the only behind-the-scenes change at ABT: In January, Janet Rollé—formerly the general manager of Beyoncé’s media and management company, Parkwood Entertainment—became the ballet company’s first Black CEO and executive director.

Although King had only worked with Royal for a short time, he had admired the dancer’s work for years. “Calvin is beautiful,” he says. By that he didn’t mean just physically arresting, although Royal is that: He stands 6-foot-1, with long limbs and chiseled cheekbones, qualities that landed him a contract with the modeling agency IMG Talent three years ago. “Truth and beauty are aligned,” King continued. “In the sincerity in his dancing, I see an honesty, a freedom.”

King proudly points out that his company, which is celebrating its 40th anniversary and features both classical and modern work, looks like America. It is perhaps because of institutions like Lines and Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater—whose corps is almost entirely Black—that classical ballet has not been under sustained pressure to diversify. “There is a dominance of white people in this art form and the exceptions are just that, they are exceptions,” says Julia Foulkes, a cultural historian at the New School. Pointing to a handful of Black dancers, she explains, “is a way to take the organization off of the hook.” To be sure, some dancers of color are stars: The most famous ballerina at ABT, and possibly in the world, is Misty Copeland, who became the first Black American woman promoted to principal six years ago.

ABT artistic director Kevin McKenzie doesn’t think the imbalance is a symptom of deliberate racism so much as a lack of entrenched pathways into ballet from underrepresented groups. “The reason there aren’t Black dancers out there in profusion who have hit the level of excellence to get into a company like [American] Ballet Theatre is because they don’t have access to the training early enough,” he says. Performing at an elite level generally requires a minimum of a decade of intense work, and apprentices at ballet companies are often in their late teens.

For this reason, it’s surprising that either Royal or Copeland landed at ABT: Royal didn’t start ballet classes until he was 14, and Copeland was a year younger. Black dancers who have thrived at classical companies were often raised in predominantly white spaces. Some were adopted by white parents, like Royal’s colleagues at ABT, soloist Gabe Stone Shayer and corps member Jose Sebastian; Harper Watters of Houston Ballet; and Michaela DePrince of Boston Ballet. DePrince’s fellow dancer in Boston, biracial principal dancer Chyrstyn Fentroy, was raised primarily by her white ballerina mother.

Royal’s early childhood didn’t provide much indication he would one day be a classical dancer. Born into a military family in Georgia, he moved three times before entering first grade. That year his parents split up and his mother took him and his brother to Palm Harbor, Florida, where they lived with his grandmother. Royal credits Grandma Linda with igniting his love of the arts: The house was filled with music, and when he expressed interest in playing piano, she bought him a Yamaha keyboard for Christmas. In elementary school, he saw a flyer for a production of The Chocolate Nutcracker, which reinterpreted Tchaikovsky’s Christmas tale through a mix of jazz, hip-hop, and African dance. “I loved the movement and I loved performing,” he recalls.

When he applied to the arts high school in St. Petersburg, Florida, Royal had never taken a ballet class before. Waking up at 5:30 a.m. to train, while negotiating growth spurts, “was a constant fight with my body,” he says. “Muscles I didn’t know I had ached.” But even after being sidelined for four months after a car accident, at 16 he competed at the Youth America Grand Prix, the biggest dance competition in the country, and was awarded a scholarship to ABT’s Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis ballet school.

When Royal phoned his mother, who works on the support staff of the Florida Department of Corrections, to tell her, she warned that even with the scholarship, New York City rents might be beyond the family’s means. “But if this is something you want,” she added, “I’m going to get you there.” That promise, he says, fueled his determination to excel in his classes.

When Royal joined the school in 2006, he was the only Black dancer of the 12 students in his class. But the real demarcation was that the others had studied the discipline a decade longer. “I was like, I’ve got to get my act together,” he remembers. He started arriving at ABT’s studios early to observe older stars in rehearsal. While he admired their prowess, he noticed the male standouts, like Cuban-born José Manuel Carreño, tended to be “jacked, like football players.” Royal wondered if his own body, lithe and long, would prevent him from ascending to principal.

ABT principal dancer James Whiteside, who performs drag under the moniker Ühu Betch, says Royal’s concerns weren’t unfounded: “From the outside, because ballet is elegant, it is associated with the effeminate. In fact, it’s surprisingly heteronormative.” The marquee roles—like Siegfried in Swan Lake and Désiré in The Sleeping Beauty—are masculine princes out of a Disney fantasy. That prototype can sometimes loom over casting. As Whiteside describes in his 2021 book Center Center: A Funny, Sexy, Sad Almost-Memoir of a Boy in Ballet, a former boss informed him he’d been passed over for the title role in Romeo and Juliet because he had worn his hair in a headband during class.

Watching the classic dances from the wings of the theater, Royal loved dissecting how different artists interpreted the roles. He mulled over the choices he would make. When he played Albrecht in 2021, he created a backstory for the prince, who seduces the villager Giselle, neglecting to inform her that he is engaged to a nobleman’s daughter. (Giselle dies in despair.) Royal didn’t want to play Albrecht as a cad, but rather as a victim in his own right, born into a world he didn’t fit into: “The experience I wanted to bring to it, why I come to the village, is because it is an exhale for me,” he explains. “I am not happy in my life up on the hill, and when I [leave], I feel closer to who I am, freer.”

It’s not hard to see a similar urge to break out of societally dictated confines in Royal’s own life. Like many of his Black counterparts in ballet, he’s been pelted with the suggestion to become a modern dancer. Or assumed to be one. Once, when he arrived at the Joyce Theater to perform with ABT’s feeder company, an usher stopped and informed him that Ailey wasn’t scheduled to go on until next week.

On another occasion, a donor cornered Royal at an afterparty and, cocktail in hand, proclaimed he’d always seen him as a contemporary dancer. Royal—who has a measured, almost mellifluous way of speaking—becomes heated when he recalls his response: “I want to prove to myself I can do something that most people wouldn’t see as a possibility for someone like me, who started ballet at 14, who is living in New York, dancing with America’s national ballet company. I don’t want to pursue another path just because it’s easier for me to go that route.”

Still, there were times he wondered if his endeavor was quixotic. Four years into his tenure at ABT, he found himself mostly understudying. But in 2014, McKenzie informed him that he had won a $50,000 fellowship to further his artistic development. Royal used the funds to tour Europe and train with masters at such prestigious companies as the Royal Ballet in London and the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, Russia. He was promoted to soloist in 2017.

King believes that attaining mastery involves internal work, in addition to intense physical exertion. “Dancers,” he tells me, “dance who they are.” That view resonates with Royal. “It was when I started to embrace myself and be honest with myself about all of the things that make me me, that’s when the whole world started to open up,” he says. Growing up in a churchgoing military family meant “don’t ask, don’t tell” was more than a theoretical concept, and that helped make Touché deeply personal for him: He knew what it felt like to long for, and fear, and finally forge a connection with another man. “In the surrender moment, it was like, ‘Oh gosh, this is what I remember dreaming what it would be like.’” It happened in his own life: At ABT, he met Polish pianist Jacek Mysinski, who is now his husband. And in 2020, Royal became a principal.

But Covid had left theaters dark, and ascending to the highest rank was a little like being handed a gift he had worked for and coveted but couldn’t open. Royal did have a chance to perform virtually, however, when New York City Center invited him to do a piece for its famed Fall for Dance festival, just months after Black Lives Matter protests had filled the nation’s streets. Royal wanted to create a piece that spoke to the moment, and he asked MacArthur-winning choreographer Kyle Abraham to create To Be Seen, set to Ravel’s “Boléro.” Royal is an uncommonly fluid dancer—which makes it all the more jarring when he surprises the audience by backing up, his hands in the air in a “don’t shoot” gesture.

Creating two works that spoke so powerfully to his personal experience was electrifying. “I see a change that I’m anxious to see more of,” he says. Up-and-comers are often compared to former stars, and Royal knew that no matter what level of technical virtuosity he achieved, he would never evoke comparisons to Mikhail Baryshnikov. “I have to carve out a whole new lane for myself and prove that I’m good enough,” he says. That lane can serve as an onramp for other people who don’t fit the traditional prototype. For ABT’s summer season, he’s performing the male leads in Swan Lake and Romeo and Juliet, roles that appear to have been out of reach for a Black star as recently as two decades ago. When Royal attempted to find tape of ABT’s first Black male principal, Desmond Richardson, he was shocked that he’d never played the lead in a classical ballet, except for Othello. “Where was his Siegfried, his Romeo?” Royal says.

Young dancers of color are taking notice of Royal’s rise. Styles Dykes, a trainee with Tulsa Ballet, remembers how he first stumbled across Royal’s photograph: “I was like, ‘Whoa, who is that?’” Dykes says. “He kind of reminds me of me.” When he met Royal at the Youth America Grand Prix competition last year, he says, he reacted the way “most kids would seeing their favorite superhero.” Royal does remember Dykes shaking, which in turn gave Royal goose bumps. “I don’t want to be the one of few,” Royal tells me. “It’s about me being the best I can be in an art form I love and inspiring other people.”

Dykes says that even before he started hunting down tape of Royal dancing, and following him on Instagram, or dreaming of seeing him live at Lincoln Center, spotting the thumbnail photograph felt like a paradigm shift: “It made me realize I can do it too.”