Fifty-two years ago, as a young fine arts photography major at San Francisco State College, Nina Hamberg had an inside view of the women’s liberation movement as a generation of feminists fought for gender equality in the workplace, in family life, and in sexuality.

Both participant and observer, Hamberg brought her camera to feminist meetings, protests, and conferences, capturing intimate moments among her second-wave comrades and the reactions of outsiders encountering her defiant, hopeful friends. But for a long time, she largely kept the work to herself; she couldn’t show the photos in her art classes at the university, full of men she remembers as mostly interested in painting nude female models.

By the mid-’70s, Hamberg had left the movement—burned out by the unrelenting feeling of responsibility to confront sexism wherever she found it. In the following years, as she moved on from that exhaustion and built a career in marketing and public relations, she came to think of her younger self as didactic and shrill, a caricature of a second-wave feminist. But all the while, she kept her photographs of the movement safe—through a house fire, a flood, and five decades of life.

Now, at 73, Hamberg is returning to her old photographs amid what she sees as an “organized, white patriarchal backlash” to the feminist victories her generation won years ago—abortion rights chief among them. “Everything we’ve achieved is dependent on having the ability to have control over reproduction of our own bodies,” she says. Returning to her records of that time has also been a period of self-rediscovery. “It’s made me feel really proud of what we did, how hard we tried, how much we cared, how passionate we were,” Hamberg says. “This is the time to have that purpose again.”

Below, in her own words, Hamberg revisits that series of work and reveals some of the smaller, more personal moments of the movement in the late ’60s and early ’70s, mostly in San Francisco. The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

The image most people have of the women’s movement is almost all about the famous activists who spoke at rallies—Friedan, Steinem, Flo Kennedy, Bella Abzug. But in reality, it was a small group movement, intimate, leaderless.

Everything we did was word-of-mouth. Everyone had a friend who wanted to learn more, wanted to join in, to start a journal, to write. Everything was totally DIY, and that, in some ways, was the best part. If you saw something that needed to be done, and you could scrap whatever you needed together, you just went with it. You didn’t have to write a proposal. You didn’t have to address a board. You didn’t ask permission of anyone. You just did it.

It’s hard to describe that kind of kinetic energy. In the fall of 1969, one teacher at San Francisco State College, Beatrice Bain, put together one of the country’s first classes on women’s issues. She was blown over when this group of women crowded into her class. There were some from NOW. Some from the Young Socialist Alliance. They were talking about the socialization process; fairy tales, and how passive the woman is; economic disparities. That was my entry point to the movement. It was like when you go to an optometrist. You’ve always had trouble seeing, the world is always a certain blurry level, and then they put those lenses in front of your eyes and say, “How’s that?” And you go, “Oh. That’s what’s missing.”

I just thought, “Well, why doesn’t everybody know about this stuff?” So I volunteered to help organize the first teach-in that December, in 1969—the first large-scale activist gathering since the strike for Black Studies, which happened right before I enrolled.

It wasn’t long before I joined a consciousness-raising group. We stayed together, the same seven women, for two and a half years. Those groups were an enormous part of building the base—and finding not our place in the larger movement, but our place in the larger world. We met every week for three hours at a time, at each other’s homes, and talked about what we were dealing with—sexism at work, family, the men we lived with. It was more than the daily things. One woman, who came from a very upper-class family, had been sexually abused by her father since the time she was a child, and she couldn’t get anyone—neighbors, family—to listen to her about that. Another woman, just a bright light of a woman, was married to a professor who was abusive. Any time she would call the police, her husband would go out and charm them, say, “You know how women are.” She had to keep fleeing him.

So it was an intense experience. We learned each other’s stories. And we realized these are not just personal experiences. The idea that “the personal is political” was a very popular thing, and it really resonated.

During those years, I felt like I understood how revolutionaries feel. It’s exhausting, it’s joyous, but you feel like your life has meaning. I knew my purpose. For three years, nothing interrupted that. So it wasn’t just the rallies and the leaders. It was us. I want it in the collective DNA that this is what that time looked like. This is who we were.

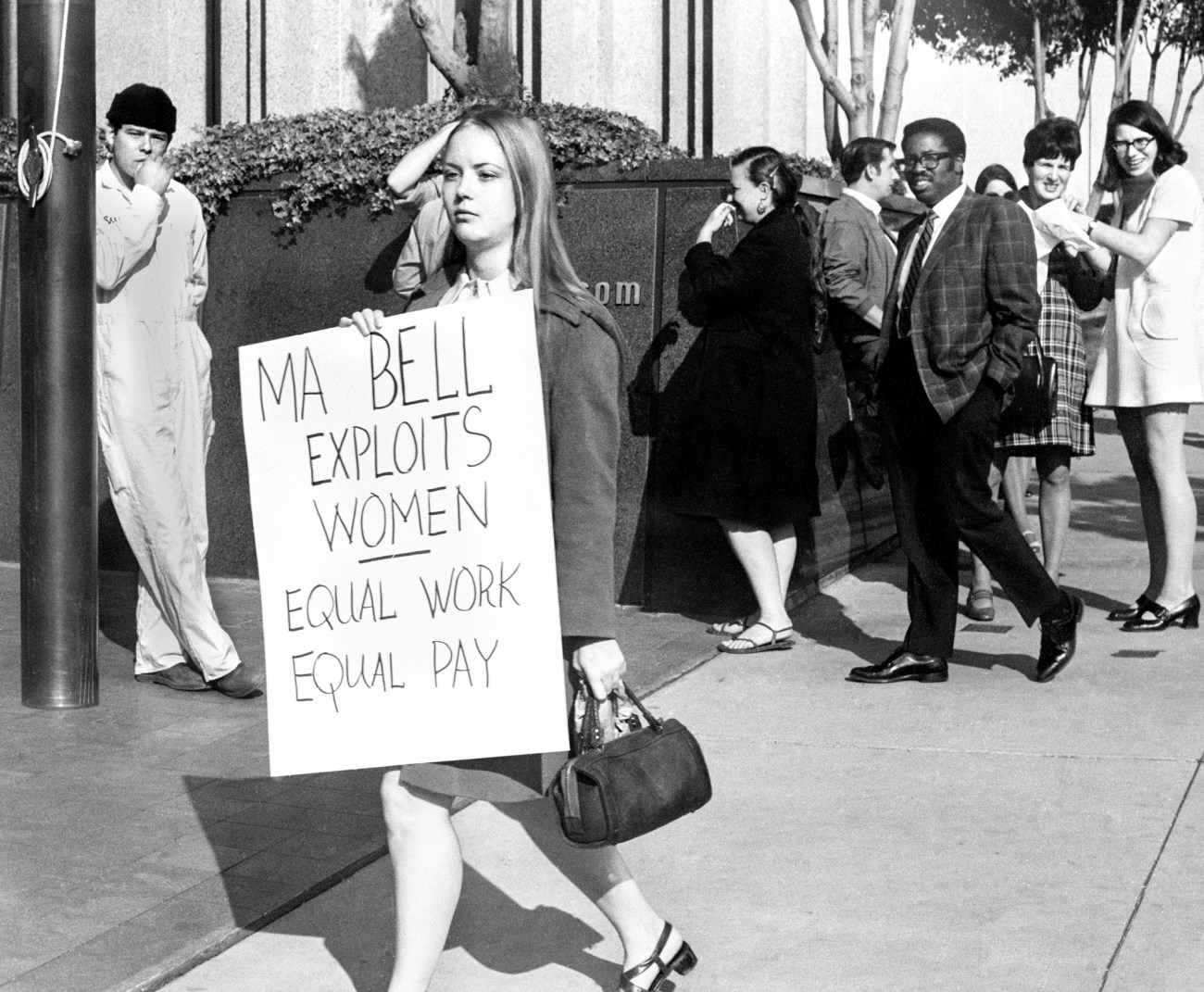

On December 3, 1969, a week before the teach-in, there was a protest outside the phone company for women’s pay. This was in the big monopoly days, and Ma Bell was a huge employer in California. Their workforce was over half women. But they had separate “help wanted” ads for men and women. “Help wanted: Female” was for operators, clerks, or secretaries. Men were everything else, including installers, maintenance, and everything to do with management. Women were earning a fraction of what men earned. A number of women applied for positions as installers, but they were turned away. We needed publicity to show what was going on.

I knew probably half a dozen of the 30 women that were there at the protest. The women doing the marching were having a really good time. They had toy phones, and all kinds of homemade signs, and they made a long and very loose line—nothing like a picket line where you’re trying to block people’s entrance. For me, I was running around checking the lighting, composing, and anticipating. I saw there was a bus stop right across the street, and I saw groups of women coming back from lunch. I knew that there probably would be more. So I waited. When a group of men came back from lunch and saw the protest, it was almost like they hit a wall. They were walking and talking, and all of a sudden, they just stopped short. And I’m right there with my camera.

There were people hiding inside the doors of the office building—mostly women, the older women who didn’t want to go open the doors for their lunch break and leave with that kind of ugliness. In my pictures of some of the women, I see anger. Some are just amazed that it was happening, like it’s funny. And I see some who seem quite condescending—like, “That’s not my problem.”

Women in our group had put together a flyer with all the facts, in terms of salary differentials and job titles. Most everybody just went, “No, no, no,” when we tried to give them the flyer. But at least one woman, she was probably a secretary, took it, and then stood by herself thinking.

I also remember there was this security guard, a man with an awful face. He had brought out guys to break heads, and he had them waiting. He was anticipating, I think, that violent, militant feminists were going to come and smash glass, or something. It cracked me up because the phone company had been asserting that the jobs that paid well were too dangerous for women.

We were young. You make these incredibly passionate decisions—in hindsight, kind of stupid decisions. Once, we got a letter promoting a conference in Detroit with Robin Morgan. It was going to be a national conference on forming an independent feminist movement. It was $10 for the weekend. I called one friend she said, “Yeah.” We called another: “Yeah.” Within a few hours, we had filled up my boyfriend’s van. It was stick shift, and only half of us could drive stick. We were so unprepared. We hadn’t mapped out the distance. We were going across the Midwest in the heat of summer, and there was no air conditioning. We had sleeping bags and tarps, but no tent. We would find state parks where it was OK to sleep on the ground.

We had been thinking the conference was going to be so big, and we would have all these great insights. We thought we’d get there and they’d be like, “How cool you’ve come all this way!” No. It was very much of a Detroit women’s group, and it was just like home—women talking and kind of working their way through different workshops and issues.

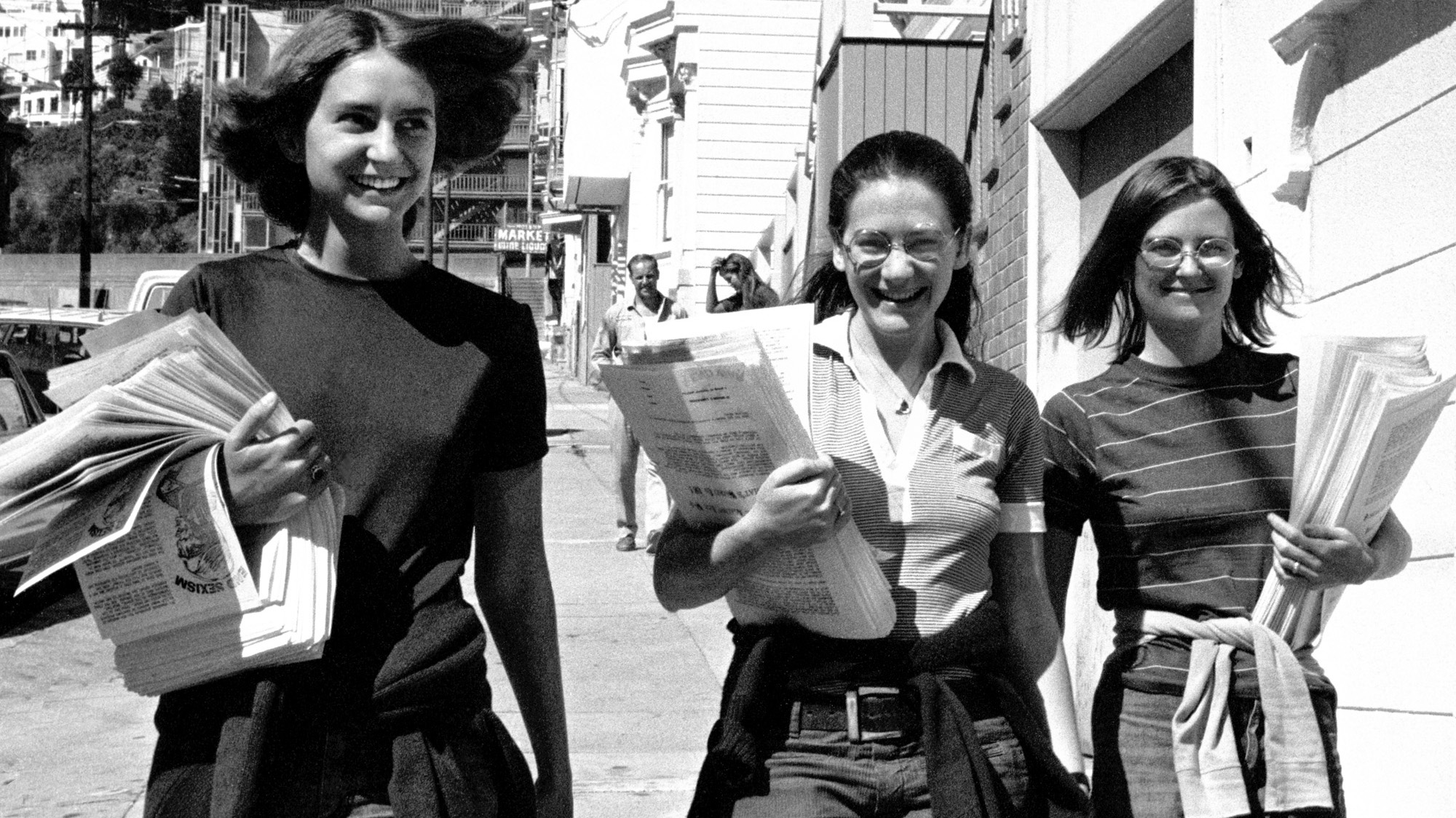

Two of my friends had put together a newsletter, Mother Lode. They brought 100 copies and handed them out. Six months later, we saw one of the Mother Lode articles in the first issue of Ms. magazine. It was Judy Syfers’ classic essay, “Why I Want a Wife.”

There was a downside to not having leaders. Meetings got called, but anyone who wanted could show up, and raise whatever issues they wanted. It went on endlessly. The socialists were saying, “This is a class struggle.” Independent feminists saw the issue as patriarchy. Lesbian groups wanted a women-centric culture. Everyone was getting tired. So somebody said, “Let’s have a retreat.” Over 100 women got together at an old lodge a short drive from the Bay Area. It was going to be an organic discussion, to find common ground.

But because it was leaderless, the meeting never got called. We laid around in the hot grass, just being bored. As a photographer, I had access to interesting faces, interesting emotions, but people were miserable. Then, once somebody found the waterhole, it became fun. People started dancing, swimming, taking showers. Some had their dogs. Just about everyone was there with a group of friends, so it got to be good.

The image that you have of the ’70s feminists is real. We were pretty hard-nosed, very didactic. We held to our language, we held to our images, had no sense—which I have now, so much later in life—that that was self-indulgent in a way. Out in the world, everyone I knew was quite armored, because there was no end to the hostility if you were walking around, for instance, wearing a feminist button. But we were not ever stiff with each other. Talking to each other—I can see it in those retreat pictures—there was so much sweetness and tenderness.

I don’t remember much of a buzz, amongst the women I was close to in the feminist movement, before the Women’s Strike for Equality in August 1970. I knew that Friedan had called it; I knew that different places were doing different things and Jean Crosby was organizing it in San Francisco, but we didn’t know what to expect in terms of turnout. The San Francisco Chronicle, whose editors despised feminism, had published an editorial building up the rally, describing it like these horrible witches from hell were screaming for the demise of everything women love.

When we saw how many people showed up, it was so joyous and so validating. There were more feminists gathered together, and more people interested in feminism, than any of us had possibly imagined. There wasn’t any antecedent in my lifetime—it had been 50 years since there had been feminist rallies, and that was for the vote.

I particularly love looking at people at that time, just because there’s so much change registering on their face—either joy, seeing what was happening, or confusion. Looking back at the pictures, on the old woman’s face, I see both confusion and longing to understand. On the face of a woman with a headband and all these kids, I just see strength and pride. To bring all those kids out for the day is no small thing, and she just looks like she feels, “Yes, yes, this is what I was hoping my daughters would get to hear.” There’s a very close up of one woman, and I just see such recognition—the sense that we felt in the consciousness-raising groups of, “Wait a minute, this isn’t just my life that I’m hearing about, this is all of us.”