In March 2015, as part of the town’s 350th anniversary celebration, local officials in Smithtown, New York, opened up a time capsule that had been buried near the town hall 50 years earlier. According to Newsday, when they pried open the unearthed milk can, they found:

a proclamation of [the] beard-growing group Brothers of the Brush, papers and paraphernalia from the town’s 300th anniversary events, a phone book, and edition of The Smithtown News, pennies from the 1950s and ’60s, a man’s black hat and a white bonnet.

“The most interesting thing that came out of the time capsule,” said the executive director of the Smithtown Historical Society, “was the smell. It was horrible. I have smelled history before; history does not smell like that.”

Time capsules often stink. At their worst, they’re full of boring documents, moldy knickknacks, and (shudder) the occasional business card. They’re generic, flat versions of a place’s official story.

But at their best, they can give future generations a sense of what it was like to live in a particular era—or to live through a particularly horrible moment in time. What delighted when everything else dispirited? What were our rituals? Our talismans? Our griefs?

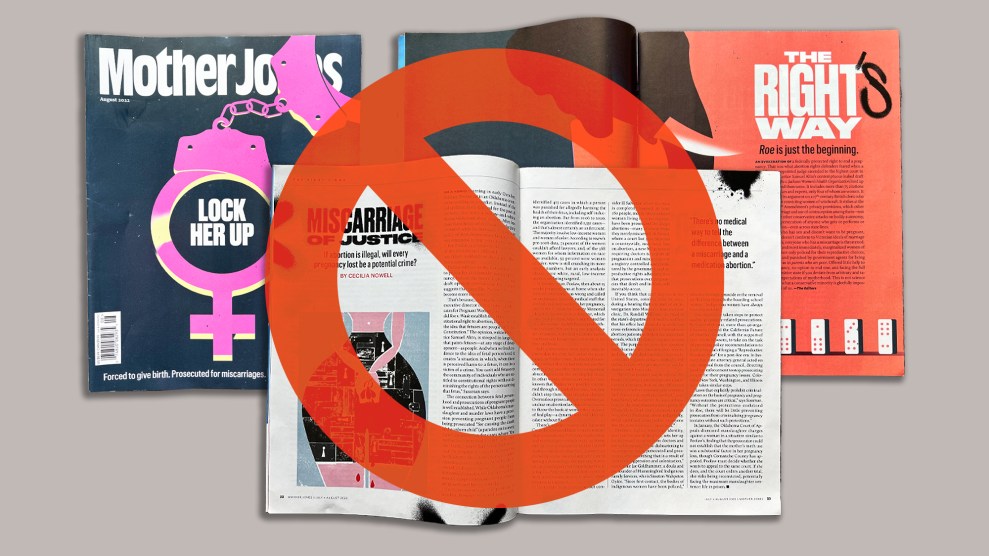

That’s the spirit of our Mother Jones pandemic time capsule. We got through 2020—barely. These things, though we never expected we would need them, helped. The year may have been a complete shitshow, but maybe, if we’re lucky, the stench will wear off soon enough.

A meat thermometer

March 2020: I had lived my entire adult life without owning a thermometer. Correction, there was a meat thermometer in the kitchen drawer, there to help a pork roast emerge beautifully from the oven—not so much to gauge the onset of my partner’s COVID infection. It didn’t have the decimal accuracy I was craving, but it did display a big “100,” useful when I stuck him like a slab of meat several times a day. It goes in the capsule as a reminder of those panicky early days, when getting an accurate read on anything, let alone body temperature, felt impossible, and time was measured in the intervals between bouts of fever and fatigue. —James West

“We Will Not Cancel Us”

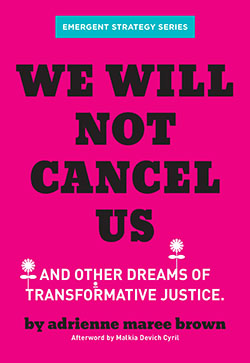

If you’re lucky, the pandemic has meant having a lot of screen time. Zoom calls, FaceTimes, Netflix binges. And if you’re anything like me, you have a love/hate relationship with every single screen you encounter. Being Very Online and Very Bored and Very Sad are never good combinations, but during a pandemic, everything feels worse.

In the summer, adrienne maree brown observed how the pandemic was shaping our conflicts. Brown is a longtime organizer, mediator, and author of two surprisingly successful books, Emergent Strategy and Pleasure Activism, that examine how we move through a world that is constantly changing us. But in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death and amid a summer of protest, she noticed a troubling tendency on the far left. “I have felt a punitive tendency root and flourish in our movements,” brown wrote. “I have felt us losing our capacity to distinguish between comrade and opponent, losing our capacity to generate belonging.”

As calls to abolish the police rang up from the streets, brown saw that her fellow movement folks had a hard time abolishing the cops in their heads. Every misguided tweet, every uncomfortable interaction, and every legitimate abuse of power was reason to cast people off onto an island of shame. When I spoke to brown in December, she boiled it all down to one simple question: “How do you want to be held on your worst day?”

She wrote a blog post that tried to grapple with some of these thoughts. The post caught fire in some corners of the internet. Some people praised her for offering a way to look critically at cancel culture. Others lambasted her for not giving enough space to survivors. But finally, people were talking. Brown eventually published the post as the short pamphlet “We Will Not Cancel Us.” The slim, pocket-sized volume includes a lengthy introduction and a list of resources for people who want to learn more. For me, it perfectly encapsulates not just the peril of 2020, but the possibility: You can start a really hard conversation online, and move it to the relative intimacy of offline spaces, and it’ll be hard—because nothing worthwhile is easy—but generative. —Jamilah King

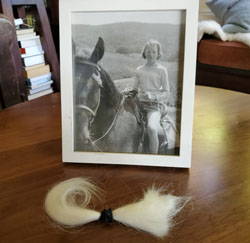

A lock of my mom’s hair

My mother was a smart, quirky, musical, and determined woman who was among the few in her generation to attend medical school. She died in late October at age 92, not of COVID, thankfully. But when she went into hospice, the people at her assisted living place initially told us we would need to get tested before visiting her. Late in the day, they said they would make an exception for hospice, so my daughter and I arranged to see her in the morning. Too late. I got a phone call at 5 a.m. Mom was gone. My wife and I went and sat with her body, still warm, to say goodbye. She had beautiful, snow-white hair, of which I took a lock—I know she wouldn’t mind. My wife had lost her own father six weeks earlier, and my children and I weren’t able to see him off, either. This awful year, and an awful president, deprived us of these final moments, and reminded us never to take them for granted. —Michael Mechanic

A photo of my pandemic pup

One day this spring, my wife told me that her co-worker’s family friend in Palo Alto had been considering sending a friend’s pup to a shelter. (Long story short, Nano’s owner fell ill and could no longer care for her.) We had a short deadline to decide whether we wanted to drive south, meet the owner by proxy at a park, and take the 2-year-old mutt home. My wife and I had talked about getting a dog in the Before Times, and I always let my existential anxiety do the talking: How would we take care of the pup while we commuted to San Francisco? What would we possibly do if we were at a rave in the city and the dog was stuck at home? How are we going to decide between the bulldog my wife wanted and the husky I, for some reason, desperately desired? These were, of course, first-world problems as we faced a devastating pandemic that upended lives across the globe.

One night, as we laid in bed, my wife showed me a picture of Nano. My heart leapt. This sounds ridiculous in retrospect, but I seriously wondered: Is that the feeling parents get when they see their baby for the first time? I thought of Sparky, the dog I had as a teenager who ran away. At a depressing moment in our humanity, we desperately needed this bundle of joy. We said yes, and we haven’t looked back since. Sure, vets are expensive. So are Bully Sticks. She taught us to slow down and appreciate the little moments in our lives—to sit and stare out into the yard uninterrupted by music or podcasts, to smile when we have the chance to go for a simple walk. Now, we’re pandemic dog parents, and we wouldn’t have it any other way. —Edwin Rios

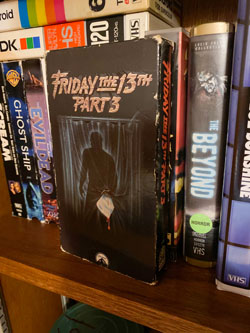

Friday the 13th Part III (on VHS)

I’ll use any excuse I can to persuade friends to come over for a movie night, especially if that excuse involves watching a horror movie. And so on Friday, March 13th, just as the country was going into lockdown, a few of my friends begrudgingly accepted my invitation to come over to watch Friday the 13th Part III. My friends, bless them, even indulged my insistence on watching the film on VHS, since I had just salvaged an old VCR from my grandma’s house. At the time, the delightfully cheesy horrors in the film were a good escape from the horrors that were playing out in the real world. We were anxious and scared as hell about the pandemic but naively convinced each other the situation would be back to normal soon enough—at least in time for those friends to come back over to watch Part IV on the next Friday the 13th. That probably won’t happen until 2022. —Matt Cohen

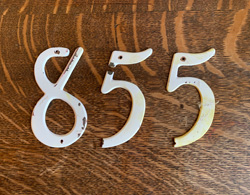

The house numbers from our old place

At some point during the pandemic—after my dad was in and out of the hospital, after months of taking turns working at the tiny desk in our bedroom with our two kids in the corner of every Zoom shot, before wildfire smoke turned the Bay Area skies a sickly orange—my wife and I decided we had to move. We’d lived in Oakland for a decade and had moved into our two-bedroom, no-yard Craftsman just weeks before our son was born. By the time our daughter came along six years later, we were already starting to feel a little cramped. But COVID made everything—every wayward pile of Legos, every overflowing laundry basket—feel impossible.

Among the flurry of home improvement projects that ensued, we had a crew paint the outside of the house. After they’d prepped and primed it, my wife noticed our house numbers were still nailed to the front of the porch. Once red, they now blended in, everything a ghostly white. She pulled them off (we’d bought some vaguely modern silver replacements from Home Depot) and stuffed them into a coronavirus time capsule we’d been keeping for the kids, along with newspaper clippings, letters my son exchanged with his friends, and a homemade face mask bearing a ninja drawn in black marker. I didn’t notice that one of the 5s had cracked until the other day, when I pulled the box down from its new spot in the kitchen of our new home, 3,000 miles and a lifetime away. —Ian Gordon

A ton of white clam sauce

I’ve rarely left my neighborhood for eight months, which meant that I quit my fast-casual habit and started buying lots of food in bulk. Beans. Pasta. Tortillas. Canned tomatoes. Except instead of the canned tomatoes, they sent me white clam sauce instead—twelve 15-ounce cans of white clam sauce. What does one do with 160 ounces of white clam sauce? I don’t know. I will never know. I’m not from, like, Connecticut. But I cannot bring myself to get rid of them either. These cans live here now. They are my cursed, soupy monolith to a cursed, soupy year.

Unless, uh, anyone wants any? —Tim Murphy

The Kingdom of Red and Gold

Since the beginning of the pandemic, my four-year-old has traveled often to the Kingdom of Red and Gold. In this magical land, superheroes, Frozen princesses, animals, and dinosaurs come together to protect their home from evil forces. The best part is that my son doesn’t have to leave his room for these adventures: They play out over the course of video chats with my parents, who have constructed imaginary landscapes and casts of characters of toys and odds and ends around their house. Along the way, my son and my parents have developed an entire mythology, including ancient beings, epic battles, and ever-shifting alliances. Kingdom of Red and Gold sessions typically last 90 minutes, but sometimes they’ve gone on for three hours. If my son had it his way, they’d never end. Not seeing my parents has been the hardest part of this pandemic for me, but witnessing the love and creativity that they pour into this project has been a profound joy. —Kiera Butler

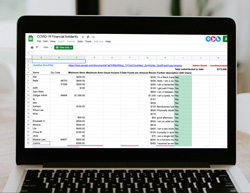

The COVID-19 Financial Solidarity spreadsheet

On March 11 of this year, somebody made this spreadsheet: “COVID-19 Financial Solidarity.” This was before the stimulus checks and expanded unemployment—before it was clear that Congress would lend us, at a penalty rate, just enough rope to hang from. People—very soon, more than the sheet could fit—asked for what they needed to get by. The sheet split into two categories: requests for over $300 and under $300. You had to say more or less who you were, what you needed, how you usually made your money. You included a Venmo or Cash App link.

The sheet is a gallery of state failure. It’s a picture of Congress going to recess with no deal, a party that scopes this situation and says, “This is an emergency! No time to lose! LIABILITY SHIELD!”

I’m 34 & recently had a heart attack. I have life saving medications that I need but can’t afford. Medicaid won’t cover them.

i am out of work and do not qualify for unemployment or stimulus i have no income at all

Black man, single father, caregiver of disabled child. I work personal security, but have been laid off until further notice… In need of groceries and medical supplies assistance. Full amount includes what Im short on for bills. God Bless.

Places much less rich than the US locked down tight, replaced lost wages—70, 80, 100 percent—froze rents, provided food, cash and medicine, made people whole. Or at least made an effort.

We did not. Who are we? We, the we of “financial solidarity,” are pretty good. We, the we of government—well, the Venn diagram of who gave to these folks and who holds power here, that’s two circles. This is the same pandemic in which America’s 600 billionaires saw their net worth increase by roughly $1 trillion. These are the human stories that add up to a trillion dollars.

I am a single mother of 3 , trying to get food for them, I’m a Home care aide and at the moment A lot of patience dont want the service

Mom of two. Out of work for the next 3+ weeks. I will gladly pay it forward once I’m on my feet again! Thank you for any help at all.

for food anything helps. I am trying to feed my family In time single dad anything is appreciated

For the benefit of future anthropologists, this is who we were in this year of hell. Sometimes we asked and sometimes we gave. Sometimes we ignored. Some of us, sometimes, cheerfully profited. Sometimes we just watched and did nothing.

Hello, I am requesting funds to help my 65 y/o mother pay her mortgage this month. She works at Wendy’s, getting paid minimum wage the last 13 years of her life. Her shifts were severely cut because of covid, so we’re worried she won’t be able to cover the cost of mortgage this month. Any help would be greatly appreciated. God Bless.

That was what sealed it for me. Years ago, before Trump and before COVID, I was reporting a short piece on Wendy’s supply chain. I found a snippet of an old Lifestyles Magazine paean to its CEO, Nelson Peltz—a Trump supporter and one of those 600 billionaires—that I still come back to sometimes:

In 1963, at a time when it wasn’t yet cool, he dropped out of the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania so he could be a ski bum… Dapperly dressed in a crisp suit, the charming and courtly Peltz, Triarc “Cash Is King” coffee cup at hand, and the world at his blinking BlackBerry’s beck and call, looks as though he were born in a boardroom.

Before we stick the spreadsheet in the time capsule, will someone text Nelson the link? —Daniel Moattar

Onion ends for stock

It began with the roasted chickens whose carcasses I refused to toss. I started cracking the bones with a meat hammer, to release the marrow, and collecting them in a Ziplock bag in the freezer. When I had enough bones, I’d toss them in a pot, cover with cold water, bring to a simmer, and skim periodically, producing a rich broth in hours.

When you make stock, you don’t need to peel the onions. If you quarter a whole onion and drop it into the simmering water, the liquid will take on the golden hue of the onion peel. I started collecting the ends of onions I would otherwise discard and hoarding them in my freezer, along with carrot tops and withered celery. When stock time came, I’d dump the frozen veggies in the pot and let the water absorb their flavor.

My desire to control that which I cannot—namely, climate change—has manifested in an obsession with food waste. But amid the uncertainty of 2020, I could always be sure that a rich, homemade stock awaited me in the freezer. —Abigail Weinberg

My pandemic reading list

As a journalist, I could barely escape doomscrolling on Twitter. But following the news has been exhausting this year. I was always on and anxious and needed a way to sleep. First, I deleted my Instagram and LinkedIn accounts from my phone. I didn’t need them for my work, and the endless information about glimmering achievements, work promotions, and photos of successful craft projects and sourdough breads was affecting my mental health. I started feeling insufficient, even though I had no reason to feel so. The cherry-picked information gave me no insight into a person’s life and yet made me feel worse about mine.

Then I started reading before going to bed. I downloaded the Libby app and started looking for books to read from public libraries. I was intentional about reading books written by people of color, particularly women. I read everyday, and I read prolifically. What started as a way to set a bedtime routine so I could snooze turned out to be the year that I have read the most in the past eight years. I read Minor Feelings by Cathy Park Hong to reflect about my own Asian identity in America. I read This Land Is Our Land by Suketu Mehta to learn about the history of why people migrate, particularly from poor countries. I read Queenie by Candice Carty-Williams and Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo and The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett and Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. I saw different parts of my own identity in these books. I shared joy and grief with their characters, and felt inspired by their courage. I reflected on my own experiences as an Asian immigrant woman. I can now hear Adichie’s voice whispering in my ear as I drive or take a walk, pushing me to observe, reflect, and document. Even the pain of the characters’ experiences only taught me that I wasn’t alone in mine, and I am grateful for that. The gratitude relaxed me and made me sleep better. My full list is on Goodreads here. —Sinduja Rangarajan

My recovery shoes

We’re a no-outdoor-shoes-inside household, which means lockdown turned us into a slippers-all-day-every-day household. At first, living in my fuzzy moccasins felt like a bright spot of an otherwise wretched situation. I’d spent much of the last year trudging along the campaign trail or in the halls of Congress in stylish booties and heels that Dr. William Scholl would surely protest if he’d lived to see them. But it turns out the flimsy, arch-less slippers weren’t so great for my joints, either. And as the lockdown turned into something more permanent, my hips and back required something sturdier.

Enter the recovery shoe, a splashy name for what are, essentially, super-cushioned, no-scuff, slip-on sneakers. They definitely look like nursing-home standard issue but have made all the difference when I’m padding around the house. My fiancée grimaced when he first saw me wear them and wonders not infrequently whether I’ll give up my “grandma shoes” when we start leaving the house with regularity again. Bad news for him: I’ve just ordered a second pair for outdoor use. They’re truly heinous AF but…isn’t taking care of our bodies a worthwhile lesson to take from 2020? —Kara Voght

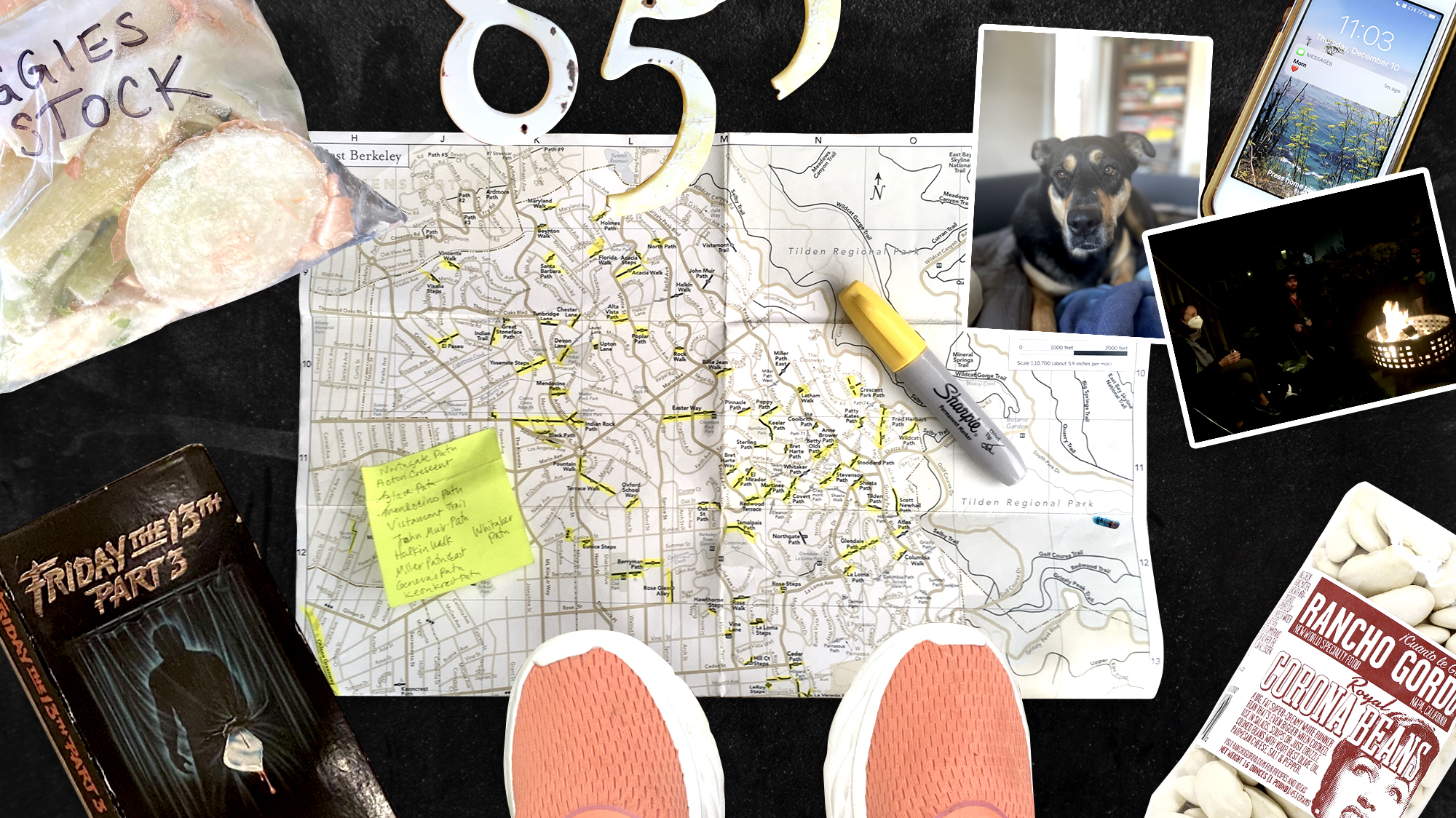

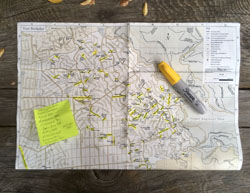

A map of every Berkeley pathway

Back when the lockdown was in its aspirational lifestyle phase and we’d already perfected our sourdough recipe, planted our vegetable beds, and sewed seven types of masks, my family—okay, my wife and I—committed to walking every pedestrian pathway in Berkeley. In the late afternoon and on the weekends, we’d drag our kids out on short forced marches, hitting four or five new paths at a time. We tracked our progress on a map published by the Berkeley Path Wanderers, the nonprofit that helps maintain the more than 30 miles of public paths that snake through the city’s hills.

Each mini-trek was different: Some paths are overgrown or unpaved, others are decorated with poetry or architectural flourishes. Many include steep or uneven stairways that reward sweat with phenomenal views. And since they run through some of the city’s poshest neighborhoods, the paths encourage a sort of YIMBY flâneurie. As we passed faux Spanish castles, mossy Tudor cottages, and mid-century boxes, we peered into hidden gardens, picked overhanging plums and loquats, and photographed houses that looked like faces. As the seasons changed, so did the political scenery: The Bernie signs and rainbows of spring gave way to BLM posters and memorials to the victims of police violence, followed by a late summer smattering of Biden-Harris signs. Our project was put on hold by wildfire smoke, but we got very close to hiking all 137 paths. Now that the air has cleared and the winter lockdown has kicked in, it’s time to break out the map again. —Dave Gilson

A stock tank

As the lockdown closed in on us, a barren side patio begged for new greenery. What flourishes along a concrete-plated wind tunnel? Oblong stock tank procured, we debated planting it with a Santa Rosa plum tree for its fruit, or bamboo for its cover. But first another plan emerged. After an hour of schlepping hot water from the tap and a kettle down to the patio, the tank transformed into a tub. Steam rising, the smell of eucalyptus, nowhere to be now. Faint constellations appeared in a night made richer black by a stilled city. —Maddie Oatman

ADHD meds

The first few months of lockdown suited me just fine—I was used to isolation after a year abroad in rural Japan. But soon, my coping mechanisms started to crumble. Being the task master and the task completer became more difficult with each passing week. Without the reliable structure of a work day and its hard boundaries (a morning commute, evening soccer practice, scattered social events) my flexible schedule quickly dissolved into a to-do list prison.

And, as expected, there came a breaking point. Like many other millennials with newly-acquired free time on their hands during lockdown, I found my way to TikTok. And thanks to its algorithms and my near-manic consumption of content, ADHD TikTok soon found its way to me. While the videos did little for my restlessness, they gave me vocabulary around ADHD I had been lacking, a validation I didn’t know I needed. The more I learned about how conflating work with worth, time blindness, rejection sensitivity, and performance anxiety can all be signs of neurodivergence, the easier it was to decide to seek help. I finally had enough time and enough of a reason to manage something that had become unmanageable on its own, to sort out whether I could give these behaviors a name other than “personal failure.”

I was surprised by the magnitude of relief I felt when I received a confirming diagnosis: a combination inattentive and impulsive type, overachieving even in my mental health issues. As it turns out, being highly functioning ADHD is only useful if the rest of the world is functioning too! But, this little blue pill has enabled me to turn down the volume on the background noise, to fall back into the focus and work ethic I pride myself on. It’s given me comfort in knowing both the problem and the solution, certainly the most amount of control I’ve felt throughout this tumultuous year. —Grace Molteni

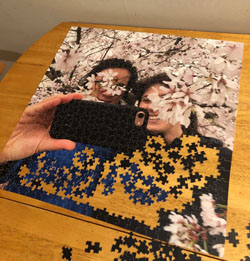

A puzzle with our faces on it

About three months into the pandemic, my boyfriend, Peter, and I received a puzzle in the mail from his parents. There was no box and no photo of the finished product. After working on it for a few hours, we realized with horror that his parents had printed a picture of us onto a puzzle. It was really difficult. Before we knew it, it was 2 a.m. on a Saturday, we were on our fourth straight episode of Tiger King, and we had started giving names like “Kevin Sharp-Angle” to the puzzle pieces we were searching for. This is what my life in Brooklyn had become. In June 2019, I was biking to the beach, hopping from one barbecue to the next, and sipping margaritas in the sunshine. Jump to June 2020 and I was inside my apartment doing a puzzle with my face on it. The puzzle sat for days unfinished on the only table in my apartment, which doubles as my work-from-home desk. Slowly I filled in a piece here, a piece there, until I had all but one piece—it turns out Peter’s parents had sent us a puzzle with a missing piece. —Molly Schwartz

Zoom (smell)

Zoom, or the smell of it, anyway. The smell that comes when the only interactions you have are on video chats and the extent that you keep things tidy and clean is limited to the background displayed by your computer camera. The smell of an apartment that has not had visitors for months and will not have any visitors for many more. The smell of garbage you put off taking out until it grows legs and walks itself out. The smell of mess and isolation and dread and retreating further and further into the last remaining clean parts of your home until there are none left. The smell of slovenliness unchecked by vanity. It’s a smell I’ve gotten used to, and that’s the worst bit: I don’t even smell it any more, but I know that if an electrician came by to fix something, they would smell it. It’s the smell of worrying that something might break and I’ll call an electrician. It’s the smell of anxiety about interacting with anyone at all. Even on the phone. What will we talk about? How we’re both “okay”? How do you maintain friendships when no one has anything to say? It’s the smell of being completely out of things to talk about. It’s the smell of a self-esteem that has no choice but to rise and fall based on thoughts you have too much time to think. It’s a smell I haven’t been able to avoid in 2020. Or, well, I guess I could have just cleaned more. —Ben Dreyfuss

Homemade comfrey salve

In normal years, my favorite place to get vegetable starts was the annual Edible Schoolyard’s garden plant sale. Unfortunately, the lively community event was canceled this year, but plants were available if you signed up for a 15-minute slot. By the time I got there the few remaining plants looked picked over, but on the way to check out, I spied a single 4-inch pot with a furry broad-leafed plant sitting off by itself. I felt a sudden spark of recognition and joy, so I added the comfrey plant to my purchases.

In experienced gardener circles, comfrey (Symphytum officinale) is well known as a bioaccumulator, and its leaves are good as mulch and compost. I remembered reading somewhere about its special healing qualities: It eases sprains and broken bones, sore muscles, bruises, and joint pain (caveat: don’t use on open wounds). A grizzly old farmer on YouTube shared instructions on a simple method to make an ointment with dried comfrey leaves, and I felt a surge of industriousness, excited for a project suitable for my pandemic-shrunken world.

One by one the internet packages arrived at my doorstep. The crockpot to infuse the olive oil with the dried herb, organic beeswax, cheese cloth, and four dozen small caviar jars with gold lids. In August, when shoots unfurled at the top of the plant, it was time to trim away my first harvest of the velvety leaves. Using the old farmer’s recipe as a guide I experimented with small batches in my kitchen lab. I added vitamin E, an antioxidant, which extends the shelf life of the salve. By the third batch I added lemon balm, and red rose petals to the botanical infusion. The most satisfying moments where in the final step when I poured the warm melted liquid into the small jars and watched them cool, lined up like so many pots of gold.

I tested the comfrey salve generously on myself, rubbing it on my right shoulder, stiff with a rotator cuff injury and my left wrist, both stubborn aches that I hoped to ease with something other than frequent tabs of ibuprofen. I have come to love the feel of the salve on my skin and the gentle herbaceous scent. I sent jars to my friends and family around the country hoping to share the good feelings and some more feedback. (I offered a jar to a friend after she had a serious injury to her knee that required surgery. She has been my most vocal enthusiast.)

Like the masks we continue to wear in public, some measures are simple things we do to protect ourselves and ease some of the pain. There is comfort in making the effort, in sharing the fruits of our labor, and in knowing that spring is around the corner, and that soon it will be time to plant something new. —Claudia Smukler

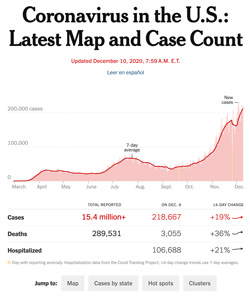

The New York Times’ COVID tracking page

It’s not sourdough starter. But the habit that stands out for me from 2020 is looking each night, or early in the morning, at the coronavirus cases and deaths totals. The abstraction of numbers, which do not convey experience, read online in a comfortable-enough home, seems like a fair representation of my fortunate distance from the tragedy, at least so far. Checking these figures is doomscrolling, I guess. It’s not a distraction. But this daily indicator of what is now more than 300,000 US deaths—this evidence of obscene government failure and lying—feels like a more honest representation of the year than any physical object that I engaged with less intently. —Dan Friedman

Flour for Pizza Day

When the world went to hell last March, my wife and I tried at first to maintain something of a daily routine for our young sons when school and daycare shut down—to preserve a shred of order as chaos descended. Inspired by parents who had created elaborate curricula for their children, detailed in Instagram-perfect social media posts, we would approximate the school experience for our boys. Only better! Perhaps this sounds familiar. Juggling our jobs and childcare, our schedule didn’t last a week. I’m not sure it survived a day. (Wild Kratts is educational, right?)

But there was one weekly event we did keep up. On Fridays, which had been Pizza Day at school, we made our own pies at home. In the early weeks of the pandemic, as panic-buying strained the supply chain, flour became as precious as, uh, toilet paper. Even after my wife forbade me from cramming another bag in our pantry—don’t judge me!—I continued to buy the stuff on the sly, afraid our supply might dry up, and with it yet another vestige of the Before Times. We had no idea what the next week or month would bring, but, dammit, Friday would be Pizza Day.

With one or both of my sons assisting, we mixed a batch of dough on Friday mornings and set it out in a covered bowl. Mark Bittman’s version was our go-to. Later in the day, I’d make a simple sauce, often a variation on Marcella Hazan’s recipe (which I like to customize a bit—I cut the butter by at least half, sub in a little olive oil, and sauté a few cloves of minced garlic before adding the tomatoes). Once the dough had risen and the sauce had simmered, we’d top our pies with whatever we happened to have on hand, then toss them in the oven or on the grill. (I’m also a big fan of my Ooni.)

I haven’t purchased flour in a few months—this jumbo bag should last us until spring. At that point, we’ll decide whether to continue our tradition. But for the first time since the pandemic began, I don’t feel like we have to. —Dan Schulman

My fire pit

Since the advent of central heat, electric lights, and modern appliances, open fire has become little more than a novelty for most of us. That’s pretty much the role my portable backyard fire pit had served since my brother bought it for me as a birthday present a few years back. Until this year. Now all social life exists outdoors (at least since Zoom gatherings stopped being fun back in, oh, April?). The warmth of the flames dissipates to a few degrees by the time it reaches a safe social distance, but their illusion of warmth makes the difference between complete isolation and periodic bundled-up, slightly-too-far-apart, and thoroughly sanity-preserving gatherings. Our debt to Prometheus is extra deep in 2020. —Aaron Wiener

My grandmother’s sewing machine

The sewing machine I inherited from my grandmother five years ago had been largely languishing under a desk until this spring, when I needed ways to entertain myself indoors. Since then, I’ve been using the 1985 Montgomery Ward, which my grandmother kept in a protective case with its original manual and signed warranty—its own snapshot in time—to replace my old retail therapy habits. Instead of spending my money on new clothes for the office, an embarrassingly large chunk of my paycheck goes towards buying lengths of linen, silk, and double-gauze cotton from my local fabric store. And there’s another silver lining to sewing in a pandemic: my masks match my outfits. —Nina Liss-Schultz

Biden Beats Trump

Why bother keeping a hard copy of anything these days? Especially a hard copy of a newspaper, unless it’s to grace the bottom of a bird cage. And yet, on Sundays I still get the New York Times, and the paper on November 8, 2020, had the banner headline: “BIDEN BEATS TRUMP: RACE IS FINALLY CALLED AFTER RECORD TURNOUT CHAOTIC TERM ENDS WITH RARE INCUMBENT LOSS.” Why bother hanging on to it when, for a mere $155, I could get a framed 11 x 17 version from the NYT store? Still, I want my own, slightly crumpled, authentic record of that agonizing, exhilarating, relieving victory. There’s the deft Trump criticism that the headline writer managed to insert in every line, like some urban, symbolist poet: the blunt force of “beats” sure to annoy the object of the sentence; the “record turnout” despite monumental efforts at voter suppression; the “rare incumbent loss” just twisting the knife for the man for whom “loser” is preferred epithet for humiliation. Then there is something about the real object, even though all this only repeats what was common knowledge the day before, the rough draft of history thing that the news once pretended to provide just occasionally still feels very real. And it does here and not in a framed version. It somehow embodies that fragile hope that maybe this Trump nightmare will really end, and with it the other hideous headlines we’ve had to endure. —Marianne Szegedy-Maszak

A paper hawk

During the depths of my four months of isolation, my only visitor was a brilliantly red male cardinal that kept attacking the window of my dim-lit basement studio. At a desperate point of loneliness, I thought of him as a friend checking on me. Sometimes he would just rest on a branch, and I’d get a brief moment to watch him watching me. The problem was that he also crashed into my window, a lot, sometimes startling me from sleep, other times worrying me he would get a concussion.

I tried everything to keep him away: I moved my plants and any fruits as far as I could from my only window; I tried keeping my blinds closed to the minimal sunlight I had. Sometimes the crashing would morph into dreams about society descending into chaos.

Some more knowledgable users on Twitter eventually informed me I could try placing a picture of a hawk in my window that would appear to the bird as if the hawk was flying towards the center. Normally, I don’t think you’re supposed to DIY it, but I didn’t have a printer and put my minimal arts and crafts skills to use by coming up with a very poor substitute of a hawk-ish cut-out made out of a scrapped NatGeo brochure I had lying around.

I don’t know how well that worked, or if it was time for him to move on, but I still think about how his appearances startled me out of isolation and into the present, recognizing the fear, anger, despair, and wonder I felt in these small moments of daily life. —Rebecca Leber

Interviewing my mother

When I was in college and visited my mom between semesters, we’d sometimes go for walks after she got home from work. Lacing up my shoes is often my first instinct when I’m sad or anxious or bored, and so when the Bay Area announced its shelter-in-place order in March, I started going on a lot of walks. Most days, I would call my mom in Illinois during at least one of them. We’re both single and were suddenly spending a lot of time alone, and it felt nice to hear her voice.

During the early weeks of lockdown, we talked mostly about the coronavirus, but eventually we needed a change of subject. So I asked if I could interview her about her childhood growing up with 15 other siblings on Chicago’s South Side in the 1960s. As I walked through Berkeley, she told me how her dad rode the rails from Montana to the Midwest during the Great Depression, after his dad was fatally kicked by a horse. She told me about growing up in one of the only white families in her neighborhood in Englewood, and her memories from the day Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. She told me about the time she sewed a designer pink pantsuit for her mom in the ‘60s, when women weren’t allowed in fancy restaurants unless they wore dresses, and how, after reading Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique as a young teen, she started calling people out for sexism at the dinner table, questioning why it was the girls’ job to do the dishes and the boys’ job to take out the trash.

As we talked, I got to know someone I thought I already knew so well, and wondered why I’d never taken the time to ask these questions before. I was surprised to hear that as a little girl, my mom—a progressive feminist who pulled me out of Sunday school—briefly wanted to be a nun. And then a hotel owner, and then an anthropologist like Margaret Mead, or a writer or a lawyer or a soldier, another career goal I would never have expected. She told me she never believed she could actually pursue these dreams, after hearing her parents talk about how nice it would be if her older sisters became teachers or secretaries. I started to think about my own path to becoming a writer, and how one of my sisters is now an attorney, and another is a lieutenant colonel in the Air Force.

My mom and I have kept talking during my walks after work. We discuss the little things, like her sewing projects or how I tripped and face-planted on a recent run, and bigger things, like when two of her siblings died over the course of a few weeks during the summer, and she had to grieve while unable to gather with the rest of her family.

I’ve spent a lot of time by myself this year, a lot of holidays without anyone. Normally in December I go back to visit, and she blows up an air mattress next to her bed and we ring in the new year and catch up and walk through the snow. We can’t do that this year, but I plan on continuing to lace up my shoes. And in some ways, because of these phone calls, I feel closer to her than ever. —Samantha Michaels

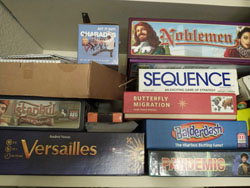

Board games

Every Saturday afternoon since May 2019, my family would get together with my husband’s cousin’s family and follow the same routine: a non-strenuous hike (for our little ones), followed by board games over cups of chai and takeout dinner. It was our social bubble and our only in-person interaction with other human beings. Our daughters were of the same age and during the time that we played, we often vigorously ignored them as they fought, made up, played, napped, or watched TV. We started playing because we had the game Pandemic at home, and what better a time to play Pandemic than when in the middle of a pandemic. But over time, our love for board games grew. We filled a whole shelf and more of our closet with Istanbul, Catan, Dominion, and Arctic Scavengers. Our predictable routine gave us something to look forward to every week. We’d analyze our moves over the week and daydream strategies to win. It was a way to escape everything around us, even our own children with whom we’d be hankering over the week while working. —S.R.

“Hard Times”

“Hard Times” reentered my consciousness when mandolin player Chris Thile released a cover of the song as part of his “Live From Home” concert series in March. The lyrics describe a farmer urging his mule forward by singing to her: hard times / ain’t gonna rule my mind / no more. Thile seemed to offer its refrain to ward off incoming doom.

As the plague crashed down, I returned to the mournful twang of the original version, written by some of my favorite musicians, folk partners-in-crime Gillian Welch and Dave Rawlings. While the song once sounded hopeful, now it had morphed to strained reassurance. The narrator wants badly to cheer up, but the tune’s dragging pace and minor chords will never fully let her. And the farmer’s story ends in sorrow: Guess he lost that knack / and he forgot that song / woke up one morning and the mule was gone. But the narrator is convinced someone still remembers the tune. She urges a tired band: Come on, you ragtime kings, and come on, you dogs, and sing / And pick up a dusty old horn and give it a blow.

In October, a profile of Welch and Rawlings revealed to me that the couple almost lost all of their master recordings to the tornado that tore through Nashville in early March. Near-tragedy led to treasure for us listeners: The musicians decided to publish some unreleased tunes, and 48 new Welch and Rawlings tracks made their way into our ears in 2020, small gifts in a time of melancholy. The spare songs don’t necessarily have a happy story to tell, but great music sure has a way of lightening the load. —M.O.

The endless cardboard pile

Earlier in the pandemic, like many of my fellow Americans, I ordered good after good to be shipped to my apartment—for me, my wife, and my pandemic pup. As 2020 comes to a close, the leftover cardboard boxes remain untouched, even as the winter gets deadlier. Let’s be honest: 2020 was a dumpster fire. The stresses of daily life and the uncertainty of the next few months, let alone the next day, mount like box after box at the entrance to my backyard. The bodies, the pain, the suffering pile up. So does care from the masses and neglect from our federal government officials. We often put our memories into boxes. Yet when I look at this pile, all I want is to desperately forget. Behind that backyard door, the sun peeks into a brighter tomorrow. But not for the thousands of Americans who died a preventable death and the loved ones who mourned their loss, the millions who lost jobs and who face evictions. I want nothing more than to set this pile of memories ablaze so that I can bask in a new day. —E.R.

My partner’s cat

Into the box, like Schrödinger, I place a cat. A rather large one, who, in this photo, looks like a turkey. Her name is Gertie Stein. Like many pets, Gertie was adopted mid-pandemic. She was a rescue. When picking her online, all seemed well, according to my partner, Emily; the only weird line in the description, she said, was that Gertie had a “large vocabulary.” We laughed. What could that mean?

“Large vocabulary” actually meant that Gertie loudly meows all night. If you, like me, have not grown up with a cat—or don’t really like cats—you might not know that a cat’s meow sounds eerily human. It has the disconcerting air of a child, unable to form actual words, crying. That noise, all night is a bit grating. Which is to say: At first, I really fucking hated Gertie.

But during 2020, confined to few spaces, one of two things happened. Either the mild annoyances of your insularity overwhelmed to the point of breaking your mind. Or, somehow, you changed. There was no option. That’s what happened with Gertie.

Unfortunately, now I really like Gertie. I send people pictures of Gertie; I talk to Gertie. I say things, when she shows me her butt, like: “That’s Gertie saying, ‘I want you to scratch my back.’” I have become that insufferable person. 2020 threw many Gerties at me, and us. But I’d like to remember the annoying stuff I learned to change, the stuff that maybe made me a little kinder and better, and even a bit happy. —Jacob Rosenberg

Rancho Gordo beans

Beans long occupied low but solid ground in the US culinary landscape: a homely, filling standby for frugal, health-conscious eaters. In 2020, two wildly disparate forces converged to change everything for the legume.

Heirloom beans—old varieties that are prized for their flavor but ignored by modern industrial agriculture—had started to become fashionable a couple of years earlier, starring in a 2018 New Yorker deep dive and a 2019 column in New York’s fashion blog, The Cut. “Everyone who just associates beans with farting needs to grow the fuck up,” one fashion-writer source told The Cut’s columnist, after declaring them “perfect” and “delicious.” This year, beans’ steady rise a foodie fixation met the coronavirus meltdown. During the early lockdowns, beans found themselves among the non-perishable staples—along with rice and oats—that people stocked up on, causing shortages. Turns out that in times of wild uncertainty, the sight of a big sack of pintos on a shelf brings as much comfort as a pot of them burbling on the stovetop.

But the run on commodity pintos and chickpeas was nothing compared to the hike in demand for heirloom beans. By early March, California-based Rancho Gordo, the most famous US purveyor of this niche item, was reporting spikes in sales directly correlated to unsteady Donald Trump press conferences. By the time I interviewed company owner Steve Sando later that month, most of Rancho Gordo’s offerings had sold out. The company and its ravenous customers would have to wait till the fall harvest for more. Sando told me soaring demand for his beans was driven mainly by a hoarding instinct among existing customers. Amid the chaos of the pandemic, he said, many people felt like events had careened out of control; and one way restore a semblance of order was to “buy way too many beans.” Another factor, I think, is that heirloom beans, as culinary luxuries go, aren’t too spendy. At about $6 per pound, Rancho Gordo beans are many times more expensive than their commodity rivals at the supermarket. But a pound goes a long way, and will set you back much less than splurging on, say, fancy olive oil or balsamic vinegar.

I asked Sando which bean variety was flying off the shelf fastest during the crisis. “Oddly enough, it’s the Royal Corona,” he said, referring to a white bean from Poland that’s so “big and fat” that “it’s almost funny.” I managed to get my hands on a bag, and here’s the delicious thing I did with them, following Sando’s advice.

Guess who’s finally off the wait list and in the RANCHO GORDO BEAN CLUB, BITCHES!!!!!!!!!!

— Deena Shanker (@deenashanker) October 20, 2020

Meanwhile, the new crop arrived, and many varieties, including those Royal Coronas, quickly sold out. For me, if I can ever get my hands on them again, they’ll always be like Proust’s madeleine—a comforting flavor that nevertheless pulls me back to the panicky early weeks of the 2020 pandemic. —Tom Philpott

My COVID band’s rendition of “I Shall Be Released”

Fear, loss, and grief defined 2020. And what made it all worse was isolation. We could not come together to share the suffering and apprehension. In defiance, four friends and I started gathering weekly—ten feet apart in backyards—to play (loud) music. It was an attempt to regain a bit of the Before Times and escape the anxiety of the election and Trump’s war on democracy.

The day after Trump’s defeat was called, our ensemble—dubbed Bandemic (thanks to my fellow players: author Adam Brookes, astrobiologist David Grinspoon, photographer Sam Kittner, and cosmochemist Larry Nittler)—opened our session with a song we had never played that seemed appropriate for both the pandemic and the election: Bob Dylan’s “I Shall Be Released.” The recording is far from perfect. But for us it was several minutes of subdued hope and camaraderie rising above a year of dread—a moment when we could envision the end of our twin national nightmares. —David Corn