The July/August 2020 issue of Mother Jones was going to look very different from what it turned out to be—and at the same time, it hasn’t changed very much at all. Here’s why: We were planning a big package of stories on corruption, a major theme that has informed our reporting for the past year.

We were digging deep on how the administration has prioritized self-enrichment for Donald Trump’s family and cronies, the only Americans he deems truly worthy of public assistance.

We were looking at how profiteers have hijacked public education, and how fossil fuel companies have fought to kneecap renewable energy. We were investigating military and immigration contracting, offshore money, hedge funds, utility companies, dark-money spenders, and those who promote racism under the guise of white victimhood.

But then the world changed—and then again, it didn’t change very much at all.

The coronavirus has brought out the best and the worst in us. It has demanded that we prioritize the collective good over narrow self-interest, and that happened—but not everywhere. Even as the vast majority of Americans sacrificed to save lives, too many of our leaders treated the disaster more as an opportunity. A chance for point-scoring, propaganda, and profit.

Meatpacking companies that forced workers to labor with little protection or hazard pay; cruise operators that shrugged off the danger until ships became floating plague wards; Fox News hosts who hectored Americans to go back to work while their own teams stayed home. And, of course, the man in the White House, who should have given us comfort and instead offered bleach.

These were not isolated acts of depravity. They were the logical extension of a system that has increasingly been engineered to reward self-dealing and cronyism over fairness and merit. A system, in other words, that has become corrupted.

Corruption does not always mean buying favors, though there is plenty of that right now. It means twisting rules that should work for everyone to the benefit of a few; enforcing them for those out of power, and suspending them for the privileged. Donald Trump’s presidency so far has been one long (oh so long) demonstration of what governance by, for, and of the 0.01 percent looks like.

But until the coronavirus arrived, one part of the picture hadn’t been completely filled in: how this kind of governance endangers the rest of us. Families ripped apart at the border, workers struggling as their bosses’ taxes got cut, generations that will suffer as a result of climate inaction—there have been many who felt the effects. But for some, there was still a degree of abstraction in the connection between White House corruption and personal risk.

No more. Now it is life and death for each of us and our loved ones (though with infuriating predictability, the effects once again fall hardest on those who already struggle the most). There is no escaping the peril, save perhaps for the island-owning wing of the Davos crowd. That’s why David Corn, in the lead essay to this issue, describes the president’s coronavirus response as “the most consequential act of corruption in the history of American governance. It eclipses Watergate, Teapot Dome, Iran-Contra, you name it.”

So when we at MoJo locked up the office and decamped to kitchen tables and bedrooms, we took our list of corruption stories with us, but we also started a new one—an intensely accelerated reporting project to investigate, document, and explain the corruption underlying the coronavirus tragedy. That’s what this issue of our magazine is about.

The centerpiece of this issue is “Failed State,” our timeline of the White House’s pandemic response. The president is already trying to rewrite history—how many times has he praised his “great” response?—and we wanted to create an incontrovertible record that transcends the chaos of the daily headlines.

We have also been investigating how the pandemic will affect people’s ability to cast a ballot in November. As one voting rights lawyer told Ari Berman for his story in this issue, “What you’ve done with coronavirus is you’ve added one more huge stressor to a system that was already at the breaking point.” Here’s a data point: Voters of color in Florida are twice as likely to have their mail-in ballots rejected as whites. For these and many other reasons, Ari writes, COVID-19 “could be weaponized to the GOP’s advantage, locking in an older and whiter electorate that stems the impact of demographic change.”

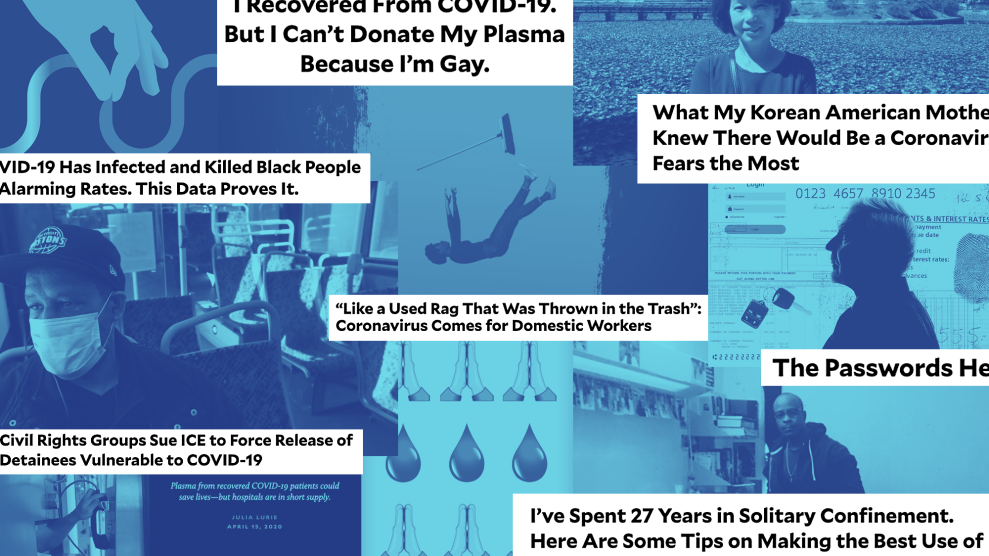

But elections are just one area in which the crisis has exacerbated all that was unjust before. Nathan Kohrman’s story in this issue exposes the perverse economic incentives that can cause pharmaceutical companies to slow-walk treatments. Esther Honig and Ted Genoways lay out in heartbreaking detail how workers were left to fall ill and die to keep the meatpacking lines rolling. Kevin Drum brings the receipts (and charts) on who really gained from the Trump tax cut, and who will cash in on the stimulus.

One of the coronavirus’s more insidious side effects has been to throw journalists off the scent of scandals not related to the pandemic—but not Russ Choma, who has tracked the president’s conflicts of interest for years and in this issue documents the reckoning Trump faces from his creditors. That’s one of the old-fashioned corruption stories we’ll keep chasing into November (and beyond), because now is not the time to let up.

Or at least, so we hope. The Fourth Estate has also been devastated by this crisis, with some 36,000 journalists seeing their jobs eliminated or reduced in just the first six weeks. That’s on top of years and years of cutbacks especially at local papers, many of which are now owned by hedge funds focused obsessively on quarterly profits. Audiences are desperate for news, but the revenue outlook is grim in a world where Google and Facebook vacuum up most of what advertising remains.

Mother Jones isn’t getting hit as badly as some because, as a reader-supported nonprofit, we rely on you, not corporate advertisers or bazillionaire investors. But we are definitely facing losses and hoping they won’t force us to dial back on our reporting. Because if this crisis has shown anything, it’s that corruption and disinformation literally kill.

But it has also shown us that change is possible. All those big corruption scandals that David Corn mentions in his piece? Each was followed by significant reform (as pandemics also often are). It’s as if we need to see the full impact of corruption before we tackle it for real.

Take heart in this: So much of what was dismissed as unrealistic just a few months ago is now happening. A massive expansion of unemployment benefits. Whole countries moving toward universal basic income. Streets closed to car traffic. It took a horrible crisis to spur these changes, but once they have been attempted, it’s much harder to say they are impossible. We’re hoping that it also becomes harder to say it’s impossible for America to have journalism without advertisers or hedge funds in control.

But that depends on ordinary people protecting the press from predatory capitalism. And we’re encouraged that so many of our readers have stepped up to support our nonprofit journalism during this crazy pandmemic-plus-election year: If you haven’t yet, and you’re able, you can join them here. And please stay safe. As this magazine’s namesake might have said, pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living, and for god’s sake wash your hands.