A group of migrants met in mid-October in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, and formed a caravan. The men, women, and children committed to help each other travel toward the United States, with dreams of a better future. Strength in numbers was the idea behind this and other caravans of migrants, which have been increasing in frequency and numbers.

For this project, photographer Brett Gundlock photographed participants of the migrant caravan that has become the target of President Donald Trump’s frequent fits of rage. Gundlock’s goal was to record the testimonials of the individuals to add context to the motives of these migrants and asylum seekers. In early November, he set up a white background in the temporary camp in Mexico City, where they rested for a number of days. He then brought the white background on the road, as they loaded trailers and slept in parking lots. The last stop Gundlock made was in Mexicali, a three-hour drive from Tijuana, where many migrants from the caravan are now currently stuck—waiting to apply for asylum or weighing other dire options, including returning to their home countries.

The future for these migrants and asylum seekers is as unclear as the day they left their home countries, but today, their journey continues.

Kenia Arias, 19, and Sury Belyini Ramos, 4, from Tegucigalpa, Honduras

“I am fleeing because they killed my mom and my brother. I am in danger too.”

–Kenia Arias

Arias had to leave her six-month-old baby at home after she says gangs killed members of her family. “It’s very hard to leave the family, and yes, it really hurts, and one does the impossible to seek the American dream, to seek a better future, a better life, because in our country, you cannot even live,” she said. “They want to kill you for nothing. Even then it is difficult to leave the country where you were raised, where you have spent all your life. It is very hard, but we have to go forward.”

Arias and her daughter posed for a photo at a migrant shelter in Mexicali, Mexico.

Eduard Manuel Manzanares, 26, and Diana María Sarmiento Ramírez, 26, from San Pedro de Sula, Honduras

“Three men robbed me at gunpoint. They took all I had. I saw the caravan on TV and left the same night.”

–Eduard Manuel Manzanares

Manzanares was traveling with his girlfriend, Diana María Sarmiento Ramírez, when they were photographed resting at a temporary camp in Palmillas, Mexico.

She had been working at a spa in San Pedro de Sula, but it closed due to the bad economy, and she decided she needed to leave in order to find work. She left her six-year-old daughter with her family. “She doesn’t want to talk to me right now because I left. When she’s mad, she won’t talk to me. I feel really bad about that, but this is for her, too. We have to move forward,” she said.

Many in Honduras fall victim to the so-called tax of war excised by the gangs—the extortion that organized crime charges to many businesses, which is a large portion of their take-home income. Manzanares, an auto mechanic, was behind in these mandatory payments to the gangs. “The biggest fear I have is returning to Honduras. But I don’t fear this journey,” he said. “When it’s my turn, it’s my turn. But I’m not going back to Honduras. We’re fighting for a purpose, it’s not because I want to live in the USA…I want to raise a family. In Honduras, you can’t do that. And if you have a job, the same crime takes the profit. You can’t work in Honduras.”

Pedro Juárez, 29, from Choloma, Honduras

“In Honduras, the authorities do not exist. They wear uniforms, but they are sold to the gangs.”

–Pedro Juárez

Three years ago, Juárez was working as a security guard when he was injured by a drunk male walking through the streets, shooting randomly.

“I was hit by two bullets. I almost died, but by a pure miracle of God, I am still alive,” he said, while resting in Mexico City. “I still have a bullet in my body [lodged in my neck] that they could not remove in Honduras.”

Jordan Yalir, aka La Tuti, 23, from San Pedro Sula, Honduras

“Many things made me leave the country. One, the discrimination that exists in Honduras.”

–Jordan Yalir

A few days before Yalir, a trans woman from San Pedro Sula, joined the caravan, she was assaulted by a group of males on her way to university. She left home at 11; her parents would not accept her. “I said, ‘Enough, I cannot continue here.’

“My dream is to reach the United States to finish my studies,” Yalir said in a temporary camp in Jesus Martinez stadium in Mexico City. “I want to continue studying economics.”

A plate of dinner served at a the Migrant Hotel in Mexicali, Mexico

Francis Eduardo, 14, from Copan, Honduras

“I’m not afraid. I have never been afraid.”

–Francis Eduardo

“I did not say anything to my family when I left,” Eduardo said. “I just left with my luggage. I did not say anything to my mom because she was not going to let me come.”

When he called her to let her know he arrived in Mexico, she cried, but she understood his motivations and encouraged him to move forward.

He was photographed at the Migrant Hotel in Mexicali.

Karla González, 19, from Ahuachapan, El Salvador, with Juan, from La Ceiba, Honduras

“I feel that I left off all my problems behind. I had terrible problems.”

–Karla González

Karla González and her new boyfriend Juan, whose last name has been withheld, posed for a photo while waiting to load into a semi-truck trailer on the outskirts of Puebla. The couple has a caravan love story: They had met on social media, but did not meet in person until they were in Tapachula, Mexico.

“When I came from my country, I never thought I would see her,” said Juan. “I came to see her in Guatemala, but I did not speak to her; I just looked at her from afar. I turned my back and left. But there in Tapachula I talked to her… We went for a walk, I started talking to her, and that’s how we got to know each other, gaining more confidence.

“I had a lot of problems in my home, but also in the street,” González said. “In the street, there is a lot of crime. I could not leave my house because there were two people trying to recruit me into the gangs. But I could not risk the life of my family, nor the life of my baby.

“For me, it is the first time I’ve left my country. You see so many things on the road. This is a remarkable experience for us. We will never forget it.”

Mainor Isaac Meléndez Suazo, a.k.a. Diablo, 16, from Atlántida, Honduras

“They wanted to kill me in Honduras. The gangs, they told me that if I did not join them, they would kill me.”

–Mainor Isaac Meléndez Suazo

“One day they threatened me in front of my mom. They told my mother that if she does not make me disappear, they would kill me there in front of my house, in front of all my brothers,” Meléndez said in the temporary migrant shelter in Mexico City.

Meléndez is an up-and-coming soccer talent; he played in one of the top divisions in his region. He was about to advance to an adult league and play with people older than him, but he could not escape the gangs. They would hang out in front of his school, pressuring the kids to join. When Meléndez and his friends resisted, the gangsters took offense. His friends jokingly call him “Diablo” after he bought a number of red jumpsuits for his trip across Mexico.

“They killed two of my friends. They killed two. They cut off their heads…Everyone knew who they were and the police did nothing,” he said.

The gangs sent threats through Facebook, photos of guns and notes saying he would soon meet their knife. This is when Meléndez knew he had to leave.

A migrant shelter in Mexicali, Mexico

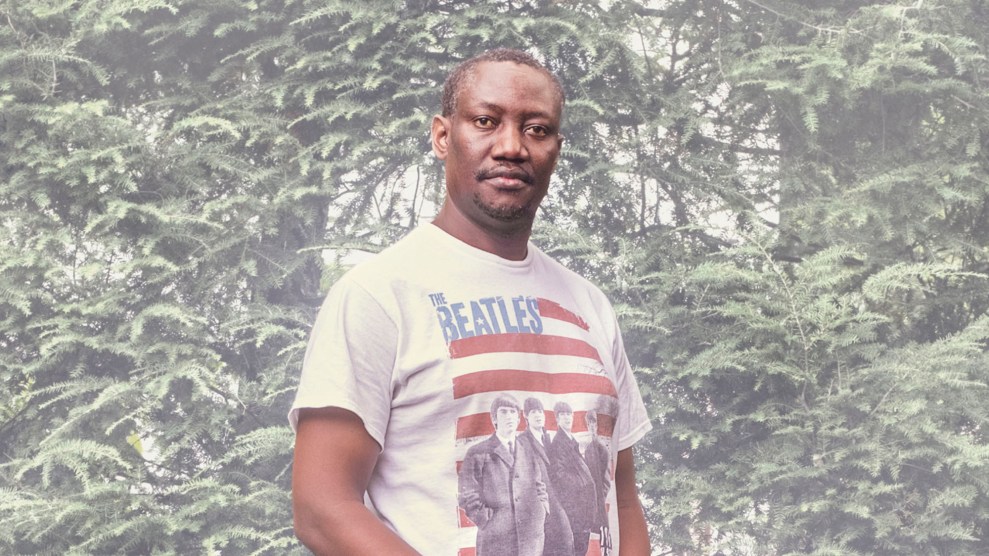

Elvin Giovanni Matute Rivera, 23, from San Marcos, Honduras

“Well, my story is hard. About 10 years ago, one of my brothers was raped. Fourteen years ago, the gangs killed another brother of mine. They want to get me as well.”

–Elvin Giovanni Matute Rivera

Matute didn’t consider going to law enforcement an option, and he didn’t want to face the gangs himself.

In addition to the violence committed against his brothers, he said, “I have a sister who was raped by her stepfather. I am not one for seeking revenge, so I left. These violent acts do not affect their souls.”

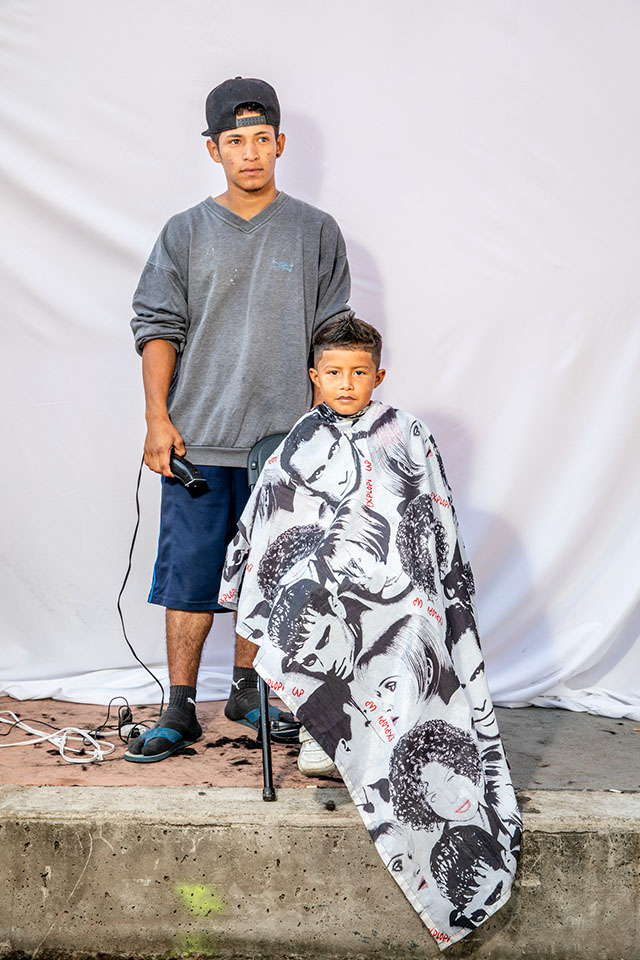

Elder Claros Martínez, 7, from Ocotepeque, Honduras, and Herson Manuel, 19, from San Pedro Sula, Honduras

“I want to get to the States, to learn English. I do not want to return to my country.”

–Elder Claros Martínez

“I am traveling with my dad and cousin,” said Martínez while getting his hair cut at the camp in Mexico City. “The road has been difficult.

“In Honduras I cut hair and helped my father make doors,” said Manuel. “They charge you just for living—the tax of war, as they say.” The day he left, he had to pay his monthly bills for his barbershop, but that did not leave him with enough to pay the gangs their fee. “’I better go,’ I said.

“I’m afraid of the gangsters. They say that if you leave the neighborhood and then later return, they will kill you. It’s like me—if I go back, they will kill me. None of us [in the caravan] can go back for the same reason,” he added.

“My dad, mom, and four brothers stayed, but my other brothers are on the way for the same reason. They’re in another caravan behind this one. I don’t know where they are. My phone was stolen and I can’t communicate with them.”

Karen Lorena Macy Pérez, 32, from Matagalpa, Nicaragua

“In Nicaragua, it has been six months since the war started. They told me they were killing students. My children were students. That is why I left.”

–Karen Lorena Macy Pérez

Macy, a single mom, was traveling with two of her children. She was photographed in the temporary camp for migrants in Mexico City.

“I just want to get to Tijuana. The United States astonishes and scares me more than the country we come from, but I have to be calm,” she said. “I am afraid that I will be separated from my children. I do not want them to take my children away.”

News of the Trump administration separating families was common in the caravan. “How can [Trump] think that he can take away the children from their mother? That is awful…That is a torture for children. A real torture.”