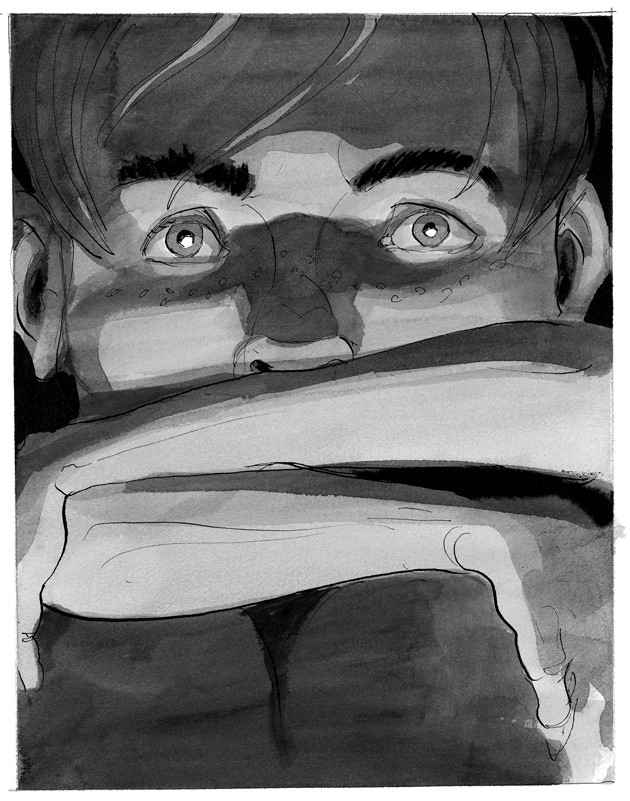

Russell, the protagonist of “Home After Dark.”

David Small, courtesy of W.W. Norton

David Small has written or illustrated more than three dozen children’s picture books, but his 2009 graphic memoir, Stitches, a National Book Award finalist, isn’t so appropriate for the young’uns. In cinematic style, Small depicts the psychological traumas of his childhood: a closeted lesbian mother whose pent-up bitterness filled the home with dread, and an emotionally distant radiologist father whose X-ray treatments of his son’s sinus problems gave the boy thyroid cancer. Small’s surgery—the large growth in his neck was just a cyst, his parents lied—left him virtually unable to speak for decades, so he spoke with his pen instead.

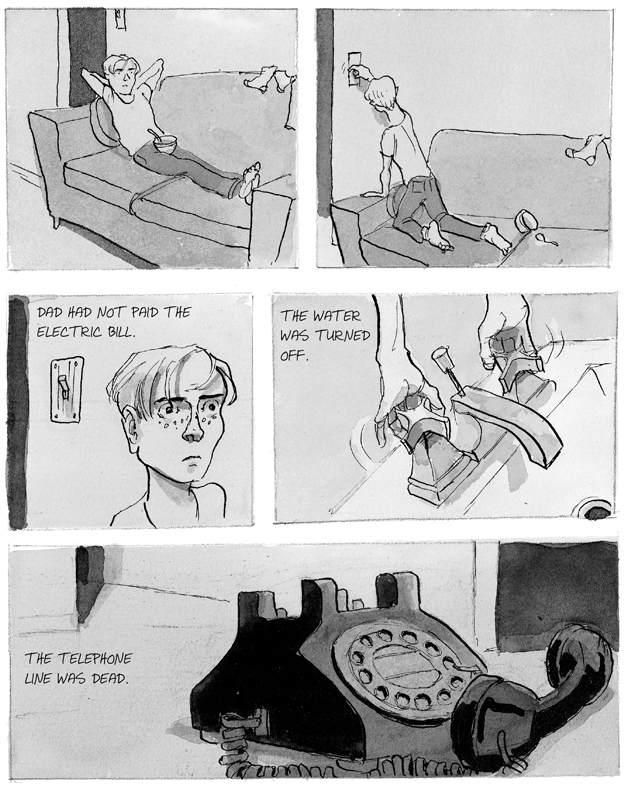

Out September 11, Small’s latest graphic novel, Home After Dark, chronicles another difficult childhood, this time fictional. Russell arrives in a small California town in the 1950s with his checked-out, alcoholic father and does his best to blend in, but he faces a dilemma when one of his new, free-range friends begins bullying a sexually confused loner. Aspects of the story can seem like a parable for America’s current political climate, but that wasn’t overt, explains Small, who resides in rural Michigan. “I’m sure it was there. It invades the mood, to say the least—especially since we live in the middle of a hot red zone.”

Mother Jones: At 73, it seems you’re still trying to process your childhood.

David Small: I’m done wading through my childhood and have paddled off into early manhood—another bog!

MJ: What inspired Home After Dark?

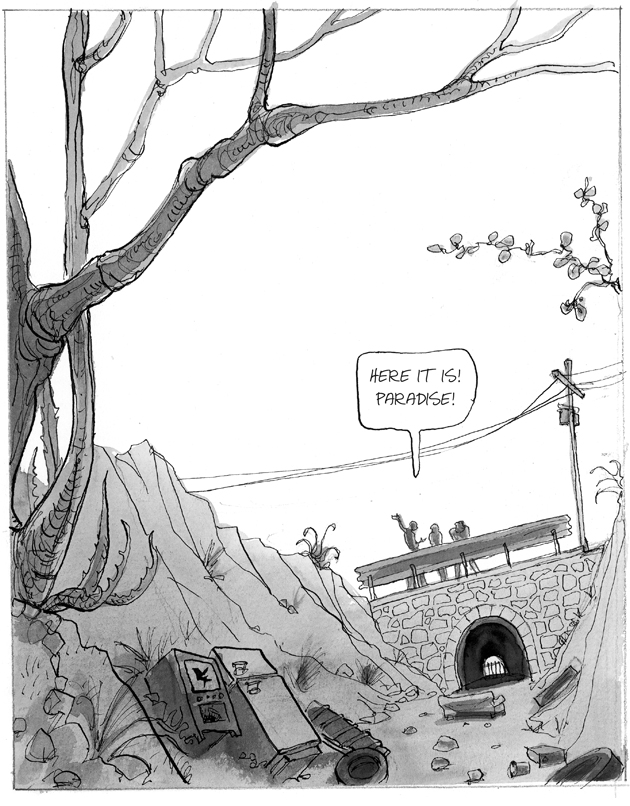

DS: I have a close friend, a great raconteur with a keen memory. One morning over coffee, he started telling me stories about one summer spent in his small town in then-rural Marin County with two friends, all free of parental control. They built a tree fort in the woods and played games in a junk-filled gully. These stories had a Huck Finn quality that made me envious. My ears perked up when a young psychopath entered the story, a kid who liked killing animals in macabre ways. When my friend and his buddies found proof he was doing this, they beat the crap out of him. End of story, except that my friend wondered for the rest of his life if they had done the right thing. I thought this was the basis for a really good book. With my friend’s permission, I began drawing pictures of his memories. I thought this was the basis for a really good book. With my friend’s permission, I began drawing pictures of his memories. The boys, the tree fort, the gully, and the animal killings are still there, but the focus began to shift to my hero, a boy more like myself—a sensitive kid with anger issues, sexual identity issues, and insecurities I knew inside and out.

MJ: Racism and homophobia were openly expressed in the 1950s. How might this story have been different if it were set in 2018?

DS: If it were set in the village I live close to, nothing would be different—except for the social media that allow bullying to spread in insidious ways.

MJ: When his dad goes AWOL, Russ is taken in by a kindly Chinese immigrant couple. Was there a reason you made his saviors immigrants?

DS: It probably had to do with them being, like my protagonist, outsiders. There probably was something metaphorical in my giving the Mahs a bigger role as the book progressed. They are immigrants—and the only truly nice characters.

MJ: Russ faces a moral crisis when his friend starts bullying Warren, the “freak.” Didn’t you see yourself as the freak growing up?

DS: I saw myself in both roles, the freak and the betrayer. As a young teen, I would have done anything to fit in. I’m sure I hurt some people along the way. I still feel guilty about that.

MJ: Betrayal is a big theme in your work: of husbands, children, friends, caretakers, secrets. What role did betrayal play in your life?

DS: Oh, man, it was the major theme in my family drama! You learned quickly not to say a word or tell a secret that could be used against you. Gifts were given, then snatched back.

MJ: Before you pursued drawing as a career, you wrote plays. Tell me about that.

DS: I was 17 and a freshman in college when I wrote two one-acts that were performed by a local professional company. The first was about a couple of losers living in a boarding house by the tracks, talking about their big dreams—The Ice Man Cometh in Tennessee Williams dialect. The other was about a woman, depressed over a lost love, being slowly seduced by her lesbian caretaker. When my parents came to see a performance, needless to say, my mother stalked out without a word.

MJ: Your cancer surgery cost you a vocal cord. How long did it take to get your voice back?

DS: It took 20 years to regain the “sort of” voice I have now. For those two decades, I couldn’t speak more than five raspy words without getting a sore throat. All of that could have decimated my social life as a teenager. Fortunately, I already had a small cadre of friends at a youth group at a Unitarian church. They were a terrific support group. But all of that ended when my mother forbade me to hang with those “liberal” kids. It certainly disappeared when, voiceless, I went into high school.

MJ: Do you find it ironic that you ended up doing children’s books?

DS: Yes, in the sense of unexpected. When I recall myself as a child, I see a very sensitive, active, imaginative kid who wanted to dance and sing and playact the stories in his head, a magical little boy who got all that spirit suppressed by these bigger, despondent creatures in charge. Maybe I needed to go back and relive that state of innocence. But my books are never weepy or doleful, and the books I’ve chosen to illustrate aren’t either. I think my forlorn beginnings have brought a kind of realism to my work, a straight-on look at the world that is infrequent in children’s literature.

MJ: What was your first big break?

DS: I was hired by Playboy for the Jessica Hahn story. She was instrumental, in an early #MeToo movement way, by helping to bring down the Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker evangelical empire. Playboy paid Hahn for a cover story about being raped by Bakker in a motel room in Florida—she undercut her credibility by appearing nude in the issue, but that was her choice. There was no real proof. [Bakker has denied raping her.] Even though I despised Bakker, I couldn’t bring myself to show him raping Hahn without proof. So, big ethical dilemma. My initial drawings showed an encounter in a motel room with a lot of innuendo but nothing of a sexual nature going on. I was feeling good about my work until I got a phone call from Playboy telling me I had to draw the rape or I wouldn’t get paid. Upshot: I needed the money and I drew the rape. So much for my unblemished karma.

MJ: A few years before he died, you did a children’s book with Sen. Ted Kennedy from the perspective of his dog. What was that like?

DS: It was fine until his handlers got involved. Kennedy told me he had picked me as his illustrator because I made him look like himself. “To most kids, I’m just an old, fat man in a suit,” he said. But when his staff got involved, the story and the art changed radically. Kennedy had to look “senatorial,” while the dog was no longer a dog whose prime interests were food and tennis balls, but a sentient being who understood exactly what a bill was and why it was so urgent that it get passed in Congress. I really liked Kennedy, but after that I vowed never to do another celebrity manuscript.

MJ: Did your parents ever encourage your art?

DS: My mother did when I was little. She grew up very poor during the Depression, and longed for a moneyed, cultured life. Recognizing, through the reactions of others, that I had a real talent for drawing, she took me to the art museum, sent me to art classes, and so on. But when I was 10 or 11 and she realized that I truly was an artist, she started backpedaling. Abruptly and cruelly, she withdrew her support.

MJ: In Stitches, your therapist tells your teenage self that your mother doesn’t love you, and you knew it was true. Could you ever bring yourself to forgive her?

DS: I came to the only kind of forgiveness that means anything: I saw my mother as a human being with her own troubled past. Her mother—my grandmother—was scary/crazy, after all. As for my dad, he was a very proud man, and that self-regard could not be violated. Even when he was in his eighties, I could not ask him about anything unpleasant or his eyes would brim with tears—he would become furious and show me the door. It’s sad to say, but since my parents have died I haven’t missed either of them for a single moment. My mother has appeared in several of my dreams, which take place in a dismal afterlife, but there was no joyous reunion. She always turns to look at me with this desultory expression, as if to say, “Oh, it’s you again.”

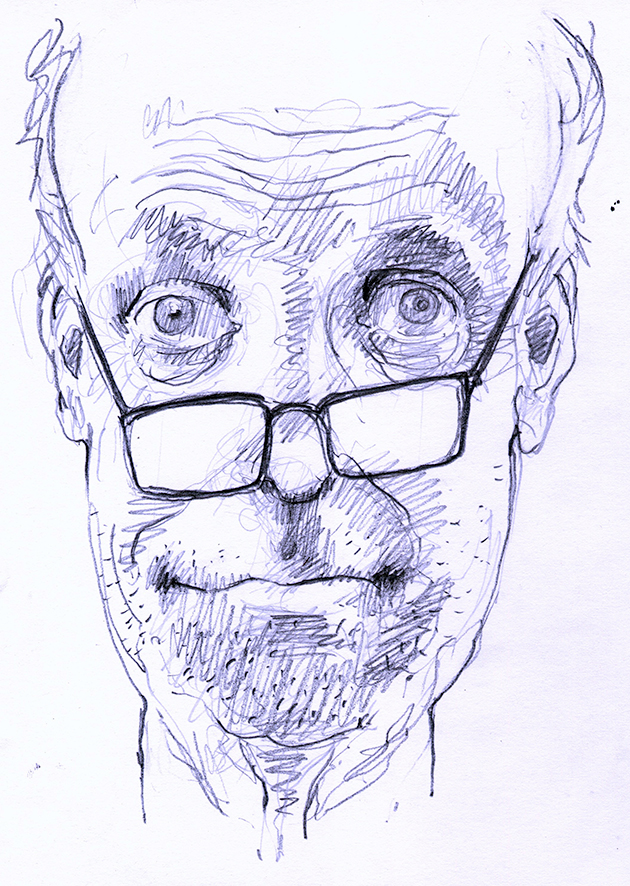

David Small self-portrait, 2018.