Michael Leckie

Behold, in order, the three most disappointing words in the English language: “To be continued.”

It’s rather different from “continued to be,” don’t you think?

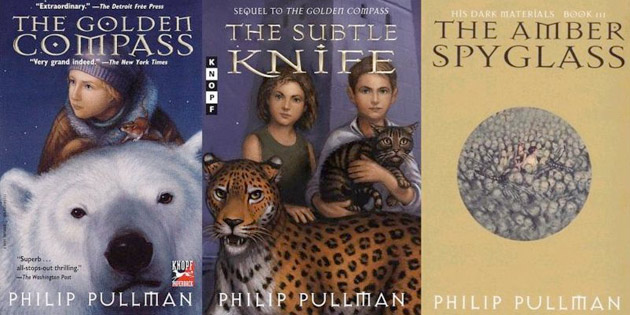

In any case, we had better pray (if you’ll pardon the irony) that 71-year-old Philip Pullman continues to be long enough to complete the remaining two volumes of The Book of Dust, the long-awaited companion trilogy to His Dark Materials, Pullman’s beloved epic consisting of The Golden Compass (1995), The Subtle Knife (1997), and The Amber Spyglass (2000).

His Dark Materials has spawned, to date, at least 18 academic books, a major theatrical production, a radio drama, a visually breathtaking but otherwise disappointing Hollywood film, and most recently, a BBC TV series that has been in development for more than a year. This is something Pullman has long desired. His epic “doesn’t need the scale of the movie screen,” he told me back in 2012. “It needs the length of a TV series.”

For now, we have the delightful first volume of the Book of Dust, La Belle Sauvage, which goes on sale Thursday—Pullman’s birthday. Sophie Elmhirst, who profiled Pullman for last Sunday’s New York Times Magazine, wrote that La Belle Sauvage “will be devoured.” She is correct.

For readers unfamiliar with His Dark Materials, which has sold nearly 18 million books to date, my condolences. But here’s a quick primer: As the series begins, Lyra Belacqua, Pullman’s scrappy heroine, is under the care (if not the control) of the scholars at Oxford’s Jordan College, to whom she was entrusted as a baby. She’s a mischievous beast, and we learn by and by that she’s an extraordinary girl, the central figure in a existential adventure that pits a powerful, fascistic, Catholic-like church (Pullman is famously antagonistic toward organized religion) against forces of good that are fighting, more or less, for people’s freedom to determine their own moral, intellectual, and spiritual destinies.

The titular golden compass, a truth-telling device called an alethiometer, of which only a handful exist, ends up in Lyra’s possession. Although she doesn’t know it, the fate of the universe (or universes) rests in her hands, and the outcome hinges somehow on both Lyra’s loss of innocence and on “dust,” an elementary particle that scholars, spies, and murderous church authorities are desperate to understand and control.

The first book of each trilogy takes place in a quaint-yet-familiar quasi-Britain wherein travel is accomplished by gyrocopter, boat, and zeppelin; electrical devices are “anabaric;” and people’s souls exist as “daemons”—external spirit animals that shape-shift throughout childhood before settling into a permanent form when their person becomes an adult.

The daemons were a brilliant and charming invention, creating pathos and intrigue and helping drive the action. Pullman told me he stumbled on the idea out of necessity. “I’d written the opening of the book about 15 times without the dæmon: A girl goes into a room, looks around, somebody comes in and she’s trapped. But it wasn’t working and I didn’t know why. Then [novelist] Raymond Chandler’s advice came true: “When in doubt, have a man come through the door with a gun.” In this case it was a dæmon…Wow, yes! Now Lyra can talk to the dæmon and the dæmon can contradict her and say, ‘No, don’t go in there, we’re not supposed to.’ It was suddenly much more dynamic.”

The real breakthrough, Pullman added, was when it struck him that adult dæmons were different from those of children, because they could no longer change their form. “That’s when I realized that I’d got hold of this big innocence-and-experience idea. The most exciting thing that’s ever happened to me as a writer was realizing that.”

Our hero in La Belle Sauvage is Malcolm, a precocious preteen who helps his parents run their inn, The Trout. He befriends nuns at a nearby priory where the sisters are caring for infant Lyra and her tiny daemon, Pantalaimon. The appearance at The Trout of powerful men with a keen interest in the child, and subsequently of representatives from the church’s reviled Consistorial Court of Discipline, draws fearless Malcolm way out of his safe zone and into a grown-up world full of mystery and danger. After a catastrophic flood throws the region into chaos, he finds himself in the role of Lyra’s protector.

La Belle Sauvage is, first and foremost, a rollicking adventure and a satisfying prequel to The Golden Compass (which was first published in the UK as Northern Lights.) But at our particular moment in history, between Twitter crucifixions of people who say anything unorthodox and the recent flirtations of Western societies with fascism, it’s hard not to interpret some of Pullman’s themes as a reminder—and a warning.

When an odious church official holds an assembly at Malcolm’s school and coerces students into joining a league of informants willing to turn in friends or family members for blasphemous actions or speech, one can’t help but consider the stain of zealotry on our own history, from the Inquisition and the witch trials on through the Holocaust—to say nothing of the existential risks posed by our tech-driven surveillance state and the rise of a vindictive president with a distaste for free speech.

In spite of a 17-year gap between The Book of Dust and Pullman’s earlier trilogy, the author remains true to his characters, tone, and pacing. His style is straighforward, and deliberately so. Much of literary modernism “seems to come out of a fear of being thought an ordinary storyteller,” he said. “So they tell it backwards and they tell it in the present tense and they cut loose the pages and shuffle them around—all that kind of stuff. When I first started writing, I tried to do that sort of thing, but I realized that there was a limited value in that. And it also made it difficult to read, and I didn’t really want my books difficult to read. Children aren’t interested in the least about your appalling self-consciousness. They want to know what happens next.”

As for what might happen in Volume II, Pullman did let on that The Book of Dust will function as both prequel and sequel, but if I were to tell you any more, he and his publishers might be tempted to separate me from my daemon. “There was a period when I had a great deal of mail specifically about His Dark Materials,” Pullman said. “Before the third book was published, that’s when I got the most. When is it going to come out? Hurry up, hurry up! What happens next? To which I could only reply, “You’ll get it when it’s finished.”