With the national parks’ much-touted 100th anniversary winding down, we’ve seen a number of books, documentaries, articles, and even hands-on, parkwide science events, all celebrating the National Park Service.

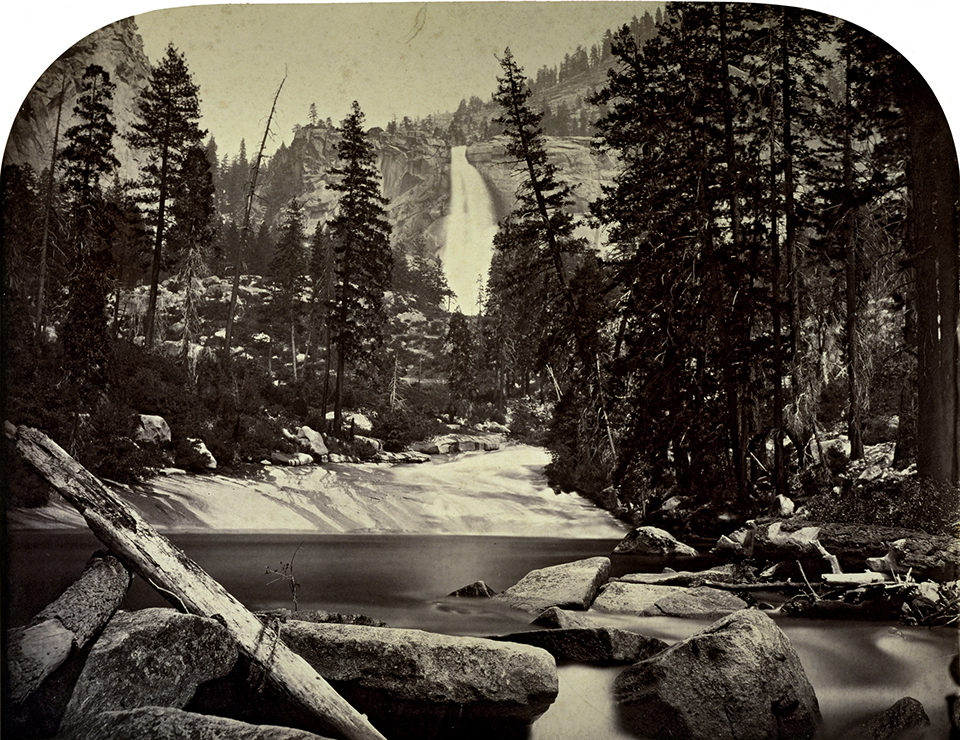

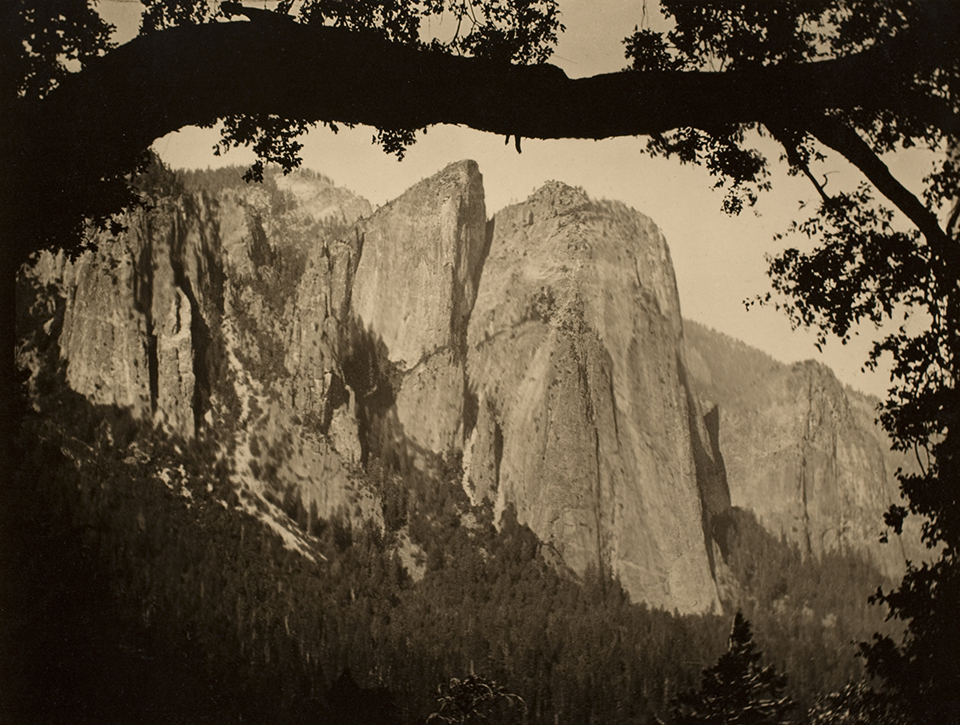

Among the books showcasing the park service, Picturing America’s National Parks, published by Aperture with the George Eastman Foundation, stands out for its examination of the role photography has played in the parks’ history. It includes luminaries, such as the earliest photos of Carelton E. Watkins and Ansel Adams’ park-defining images as well as more recent work by Lee Friedlander and Rebecca Norris Webb. This book shows how photography not only helped shaped the national park system, by encouraging tourists to visit, but also had a very real impact on the creation of it.

Throughout the parks’ 100-year history, photographs have helped draw visitors so they can experience the majesty of the parks themselves. As we all know, whether it is a photo of the Grand Canyon or Isle Royal, a picture is never as powerful as seeing these spectacular places in person.

William Henry Jackson’s early images of Yellowstone’s greatest features, such as Old Faithful and the Lower Falls, along with artist Thomas Moran’s classic painting The Grand Canyon of Yellowstone, brought the majesty of the West to leaders in Washington, DC. These images helped persuade Congress and President Ulysses S. Grant to name Yellowstone as the first national park in 1872.

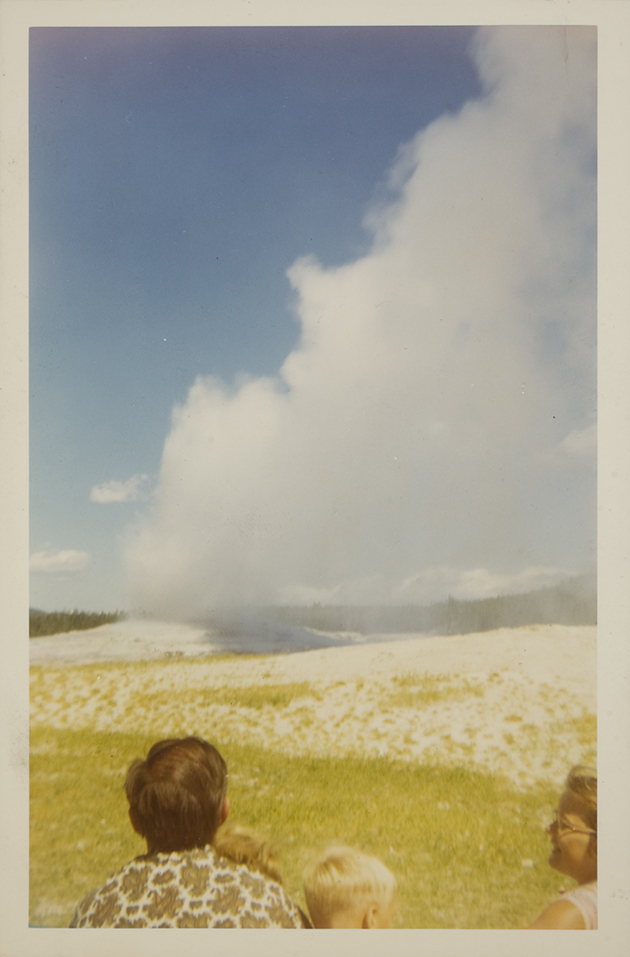

Picturing America’s National Parks showcases a number of photographers whose work reflect trends in photography over the years. You have early, large-plate photography, sometimes hand-colored. There’s the technical perfectionism of Adams’, Edward Weston’s and Minor White’s images. The book also showcases more pedestrian photography, such as postcards and tourist images over the years of iconic park sights like the Old Faithful Geyser. As you see the clothing and photography styles evolve in the photos, these images give a fascinating look at how the landscape of the parks changed to accommodate swelling numbers of tourists.

The book is arranged chronologically, thus when the ’50s and ’60s come into view, you have photographers like Garry Winogrand and Joel Sternfeld pulling back with a wider lens, focusing as much on the visitors as the landmarks they came to see. This trend culminates in Roger Minick’s excellent series Sightseers, which he shot in the 1980s, focusing specifically on tourists.

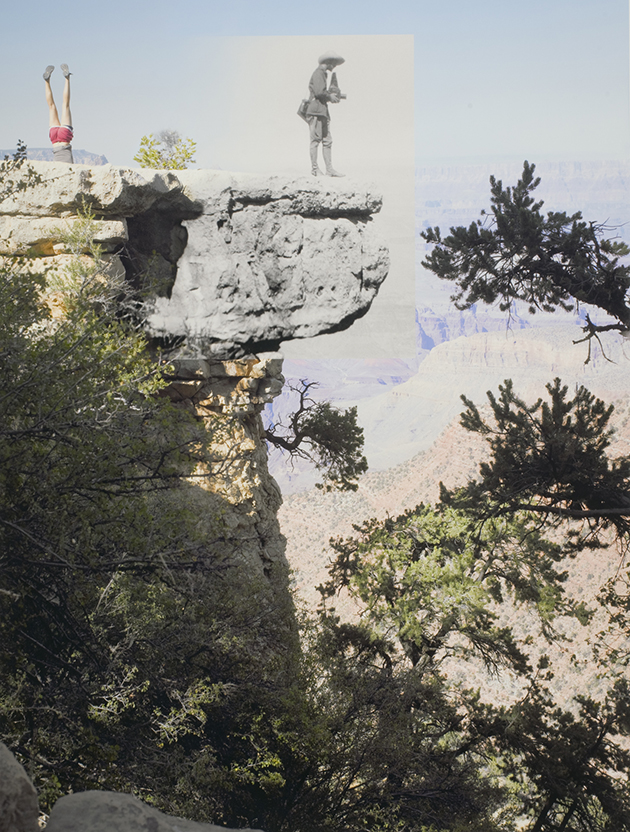

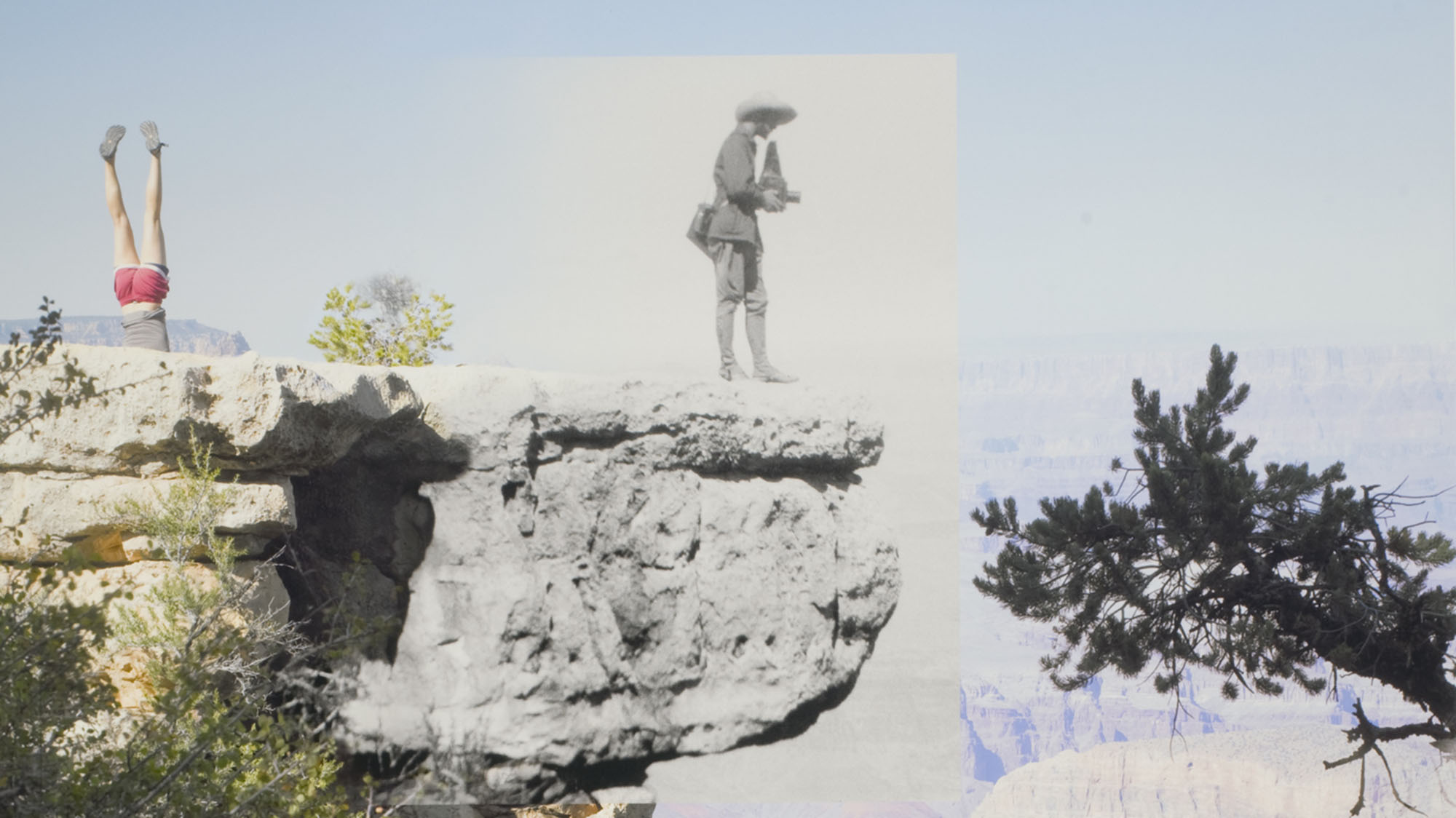

As the book brings us to more modern times, we see more artistic takes on picturing the parks, such as Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe’s project Reconstructing the View, which incorporates historical images repurposed in recently photographed vistas. All in all, it’s a truly excellent survey of photography of the national parks, even if the work selected leans particularly heavy on the parks of the West, such as Yosemite, the Grand Canyon, and Yellowstone.

There’s so much more to the national parks.