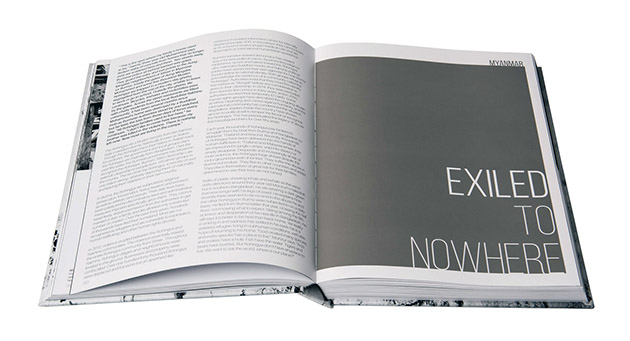

Greg Constantine began working on what would become the Nowhere People project in 2005. A year-long project spurred by meeting North Korean defectors in China morphed into a decade-long investigation that took him around the world. Initially Constantine focused on Asia: documenting the lives of stateless people in Bangladesh, Malaysia, and Nepal. Part of that work lead to the Exiled to Nowhere book, which examined the plight of the Rohingya people in Burma.

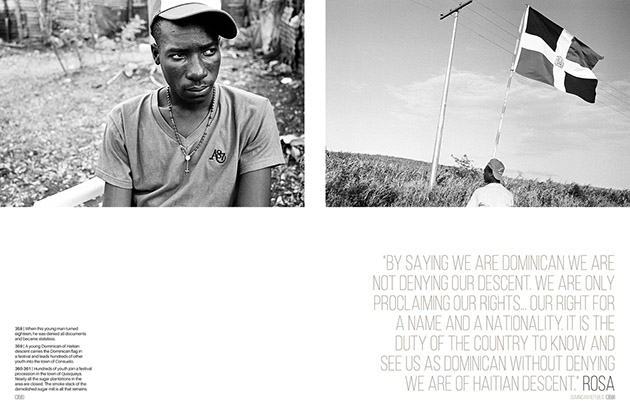

As he got deeper into the subject, Constantine took an ambitious leap and expanded the work to Africa, working with the UN refugee agency in Kenya and Ivory Coast. He traveled to Sri Lanka to photograph the Hill Tamils, and to Ukraine, the Dominican Republic, and then the Middle East: Kuwait, Lebanon, and Iraq. Most recently, Constantine’s turned to Europe—the Netherlands, Italy, Serbia, Poland, and Malta—visiting 18 countries in all.

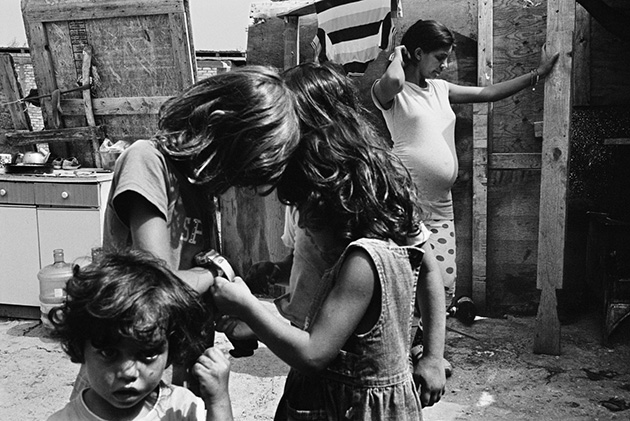

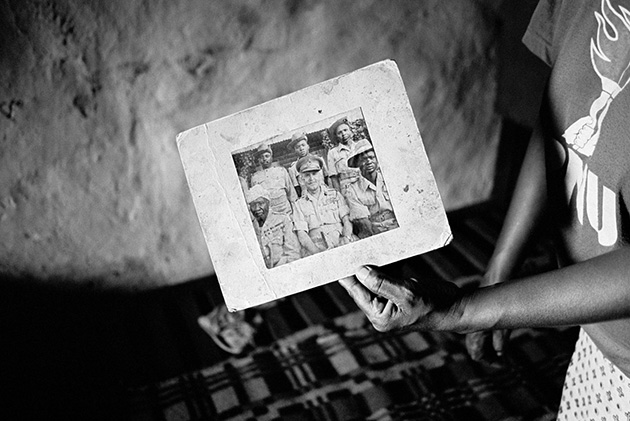

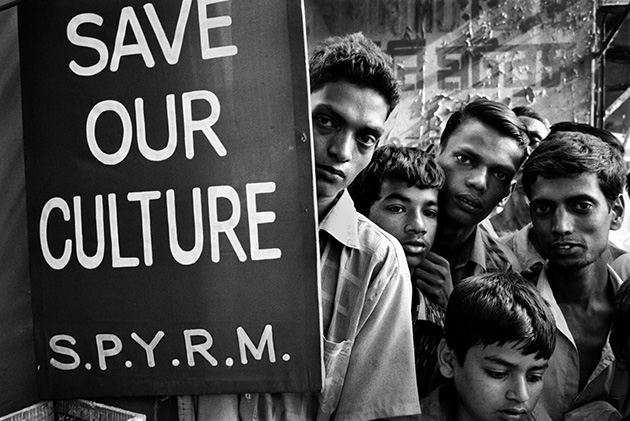

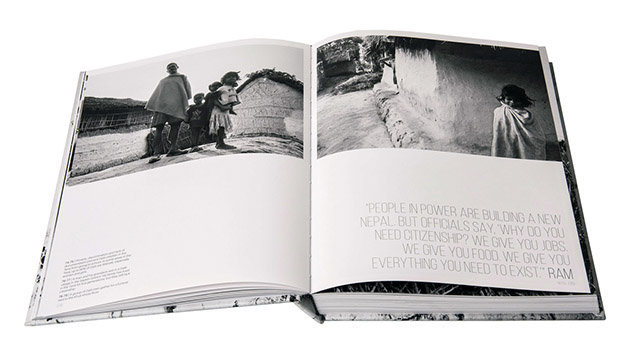

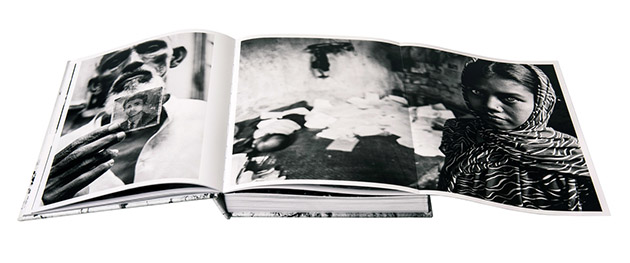

Constantine’s book Nowhere People brings you into the homes of the Rohingya, Roma, Crimean Tartars, Nubians, Hill Tamils, Haitians living in the Dominican Republic, Kurds, Dalits, Ahwazi, Bihari, Bukinabé in Ivory Coast, and Bidoons of Kuwait. It’s a bit of a blur. The similarity in how these people live and suffer helps bring a sense of scale to the problem.

The book is a deep dig into a rather unsexy story about people who have been exiled from their home countries or are not accepted by their birth countries simply because of their ethnicity or where their families may have come from. Often they can’t leave the country that doesn’t want them because they have no papers. They have no passport, no birth certificate, nothing to verify who they are or where they came from. They’re stuck.

Constantine explains:

Without citizenship, stateless people belong to no country and are refused most social, civil and economic rights. In most cases, they cannot work legally, receive basic state health care services, obtain an education, open a bank account or benefit from even the smallest development programs. They are often deprived the freedom to travel, the right to own land or possess essential documents like an ID card, birth certificate or passport. As non-persons, they are excluded from participating in the political process and are removed from the protection of laws, leaving them vulnerable to extortion, harassment and any number of human rights abuses. Statelessness paralyzes them in poverty and constructs challenges that plague every aspect of a person’s life.

The book, in its scope and depth, brings to mind a vast Sebastiao Salgado project (think Migrations) or Ed Kashi’s excellent Curse of the Black Gold book on the Nigerian oil industry.

Nowhere People is the kind of project that young documentary photographers often dream about pursuing without fully taking into account how much time it will take and, importantly, how much money it will cost. Constantine worked with a number of NGOs and got grants to continue the project from such notable organizations as the Open Society Institute, the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting, the Oak Foundation, the European Network of Statelessness, and Blue Earth Alliance, among other supporters. The back end of a project like this, stringing together the amount of support Constantine did, is every bit as impressive as the photography.

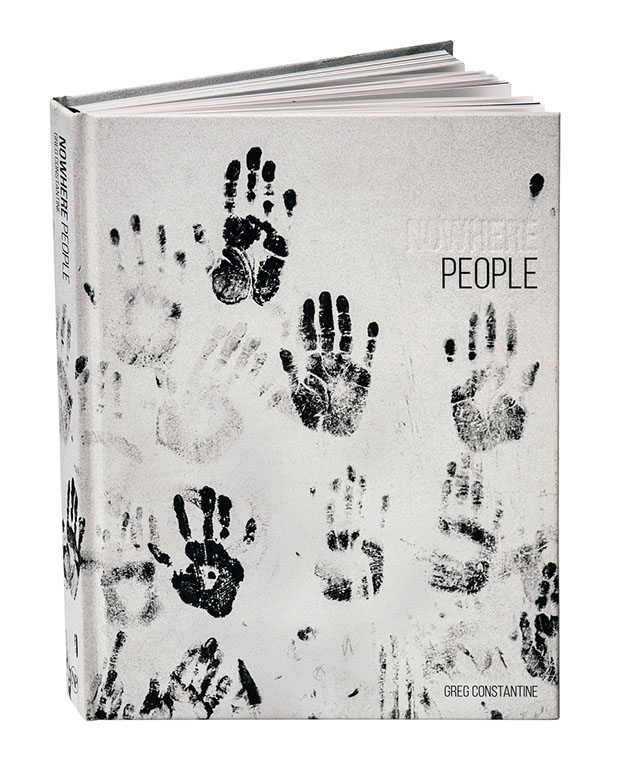

A quick note on the book itself: It’s a hefty, beautiful beast. From the textured, embossed cover to the excellent black & white reproductions and smart layout, including nice foldout pages allowing for big, gorgeous horizontal images, it’s a book that as an object itself stands out.

Nowhere People is available November 3, 2015 from nowherepeople.org and Amazon.