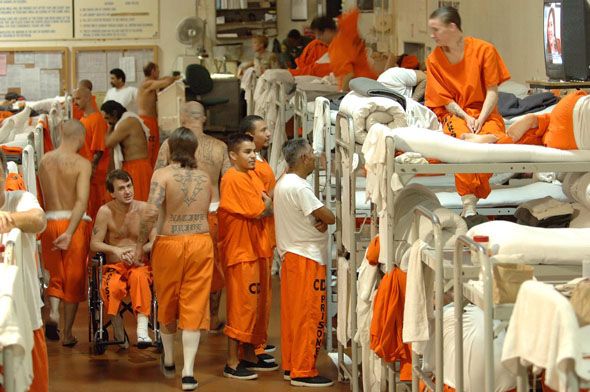

Maybe this guy should try using Panoply.<a href="https://www.flickr.com/photos/90616585@N06/8413945044/in/photolist-cDhJfA-4gSNmt-dPvEJ1-ffQHUp-qbGea-aTiY8v-aXj55D-6LcUAD-vwpwP-aTiXXr-6dGXp9-qaAvQf-vbhFM-aTiWLn-vbhFv-vbhFG-6Pc5PU-nXKzCz-smb98-vb1jZ-8MSuws-cJnRLJ-8Zyn3f-82JV7S-pbc4DP-bpeRX-r61otT-rBmVNw-vb1jU-5SGaXu-vbhFy-vbhFD-vbhFq-vb1k4-8doPc1-7q1jZJ-6jjhNJ-ag88Lh-ag87m9-aTiVCx-Wc4xq-9cWajT-9v1RgG-9v1Q85-9v1Q1h-9uXQTF-9uXPNz-9v1Q4E-9v1Q2Q-9v1PXE">goldverikurtarma-07</a>/Flickr

Rob Morris started his PhD in media arts and sciences at MIT without having taken a single computer science class—”which, in retrospect, was really one of the dumbest things I’ve ever done,” he says. Scrambling to keep up with classmates who had far more coding experience, he found himself spending a lot of time on Stack Overflow, an online forum where programmers help each other write and debug code. He got better, but he couldn’t stop stressing out about what he saw as his inferior skills. Then he had an idea: “Just as we can get a crowd of people to help us find and fix bugs in our code, perhaps we can get people to help us fix bugs in our thinking.”

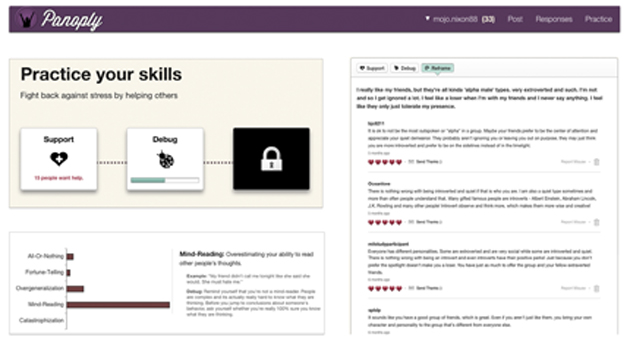

That insight led Morris to develop Panoply, an online tool that crowdsources treatment for depression and anxiety, which he’s now turning into a consumer app. (Currently the app, which is called Koko, is invite-only; prospective users can sign up here.) People with depression and anxiety often have irrational thought patterns that cause them to perceive normal situations in a distorted, often negative way. To break those thought patterns, Panoply relies on a technique that psychologists call cognitive reappraisal.

When a user is upset—say she’s lost her job and she doesn’t feel like she’ll ever find another one, or her roommate walked past without saying hi and she thinks he’s angry at her—she posts a description of the situation as she perceives it. Then other users point out specific ways in which she might be falling into distorted patterns of thinking and try to help her reframe the situation. Maybe the right job just hasn’t come along yet; maybe the roommate had a bad day at work and just doesn’t feel like talking.

A study published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Medical Internet Research this week suggests that Panoply’s engagement tactics—and its overall approach to improving mental health—are effective. Of 166 study participants who had previously exhibited symptoms of depression, those who spent three weeks using Panoply for at least 25 minutes a week ended up significantly less depressed and better at cognitive reappraisal than those who spent three weeks doing an expressive writing exercise, a typical treatment for depression.

Morris teamed up with Stephen Schueller, a clinical psychologist from Northwestern University, to design Panoply. But he has his own background in psychology: He majored in it as an undergraduate at Princeton, and he briefly worked in a clinic after college. He says he came to MIT knowing that he wanted to use technology to educate people about psychological health, especially people who wouldn’t or couldn’t seek traditional therapy.

Panoply wasn’t Morris’ first approach. “Being at the MIT Media Lab, you’re surrounded by so many crazy futuristic toys,” he says. “There’s a group next to mine that just has all these robots walking around and interacting with people. Of course I thought, I can steal one of those robots and create a robot therapist that follows you around.” He settled on creating a social network instead when he realized that copying the addictive qualities of Facebook and Twitter could solve a problem with existing mental health apps: There’s nothing to keep users coming back day after day. “They feel a bit like homework,” he says.

Like other social networks, Panoply pings users every time someone comments on one of their posts. Morris hopes the community-building aspect of the site will keep people engaged. “It’s a really powerful feeling to spend a few minutes thinking really hard about how to write two to three sentences to help someone and then finding out that you made someone feel better,” he says.

Still, Morris says he plans to roll out the mobile app slowly, in part so that he can ensure it won’t be plagued by trolls. He already has some safeguards in place. Every time someone posts a response, Mechanical Turk workers get paid a penny each to determine whether it passes certain criteria before it goes live. In addition, algorithms search the text of each post and quarantine those that feature potentially offensive words or phrases.

Even though the study of Panoply focused on depression symptoms, Morris says he doesn’t want to pigeonhole his app as “a depression app.” He prefers the term “stress-reduction app,” because he worries that stigma around the word “depression” will drive potential users away. He wants people to feel like they can use the app even if they don’t have a diagnosed mental health condition, if they’re just having a bad day. “I think in our society we spend a ton of attention on fitness and how to eat,” he says. “Not so much on emotional well-being.”