<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml%3Flang=en&search_source=search_form&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&searchterm=newspaper#id=135932729&src=VYMpwM0ZeEacpPqcAGe2TQ-1-32">ConstantinosZ</a>/Shutterstock

This story first appeared on the TomDispatch website.

It was 1949. My mother—known in the gossip columns of that era as “New York’s girl caricaturist”—was freelancing theatrical sketches to a number of New York’s newspapers and magazines, including the Brooklyn Eagle. That paper, then more than a century old, had just a few years of life left in it. From 1846 to 1848, its editor had been the poet Walt Whitman. In later years, my mother used to enjoy telling a story about the Eagle editor she dealt with who, on learning that I was being sent to Walt Whitman kindergarten, responded in the classically gruff newspaper manner memorialized in movies like His Girl Friday: “Are they still naming things after that old bastard?”

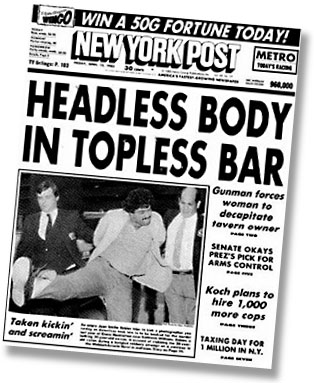

![]() In my childhood, New York City was, you might say, papered with newspapers. The Daily News, the Daily Mirror, the Herald Tribune, the Wall Street Journal…there were perhaps nine or 10 significant ones on newsstands every day and, though that might bring to mind some golden age of journalism, it’s worth remembering that a number of them were already amalgams. The Journal-American, for instance, had once been the Evening Journal and the American, just as the World-Telegram & Sun had been a threesome, the World, the Evening Telegram, and the Sun. In my own household, we got the New York Times (disappointingly comic-strip-less), the New York Post (then a liberal, not a right-wing, rag that ran Pogo and Herblock’s political cartoons) and sometimes the Journal-American (Believe It or Not and The Phantom).

In my childhood, New York City was, you might say, papered with newspapers. The Daily News, the Daily Mirror, the Herald Tribune, the Wall Street Journal…there were perhaps nine or 10 significant ones on newsstands every day and, though that might bring to mind some golden age of journalism, it’s worth remembering that a number of them were already amalgams. The Journal-American, for instance, had once been the Evening Journal and the American, just as the World-Telegram & Sun had been a threesome, the World, the Evening Telegram, and the Sun. In my own household, we got the New York Times (disappointingly comic-strip-less), the New York Post (then a liberal, not a right-wing, rag that ran Pogo and Herblock’s political cartoons) and sometimes the Journal-American (Believe It or Not and The Phantom).

Then there were always the magazines: in our house, Life, the Saturday Evening Post, Look, the New Yorker—my mother worked for some of them, too—and who knows what else in a roiling mass of print. It was a paper universe all the way to the horizon, though change and competition were in the air. After all, the screen (the TV screen, that is) was entering the American home like gangbusters. Mine arrived in 1953 when the Post assigned my mother to draw the Army-McCarthy hearings, which—something new under the sun—were to be televised live by ABC.

Still, at least in my hometown, it seemed distinctly like a golden age of print news, if not of journalism. Some might reserve that label for the shake-up, breakdown era of the 1960s, that moment when the New Journalism arose, an alternative press burst onto the scene, and for a brief moment in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the old journalism put its mind to uncovering massacres, revealing the worst of American war, reporting on Washington-style scandal, and taking down a president. In the meantime, magazines like Esquire and Harper’s came to specialize in the sort of chip-on-the-shoulder, stylish voicey-ness that would, one day, become the hallmark of the online world and the age of the Internet. (I still remember the thrill of first reading Tom Wolfe’s “The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby” on the world of custom cars. It put the vrrrooom into writing in a dazzling way.)

However, it took the arrival of the twenty-first century to turn the journalistic world of the 1950s upside down and point it toward the trash heap of history. I’m talking about the years that shrank the screen, and put it first on your desk, then in your hand, next in your pocket, and one day soon on your eyeglasses, made it the way you connected with everyone on Earth and they—whether as friends, enemies, the curious, voyeurs, corporate sellers and buyers, or the NSA—with you. Only then did it became apparent that, throughout the print era, all those years of paper running off presses and newsboys and newsstands, from Walt Whitman to Woodward and Bernstein, the newspaper had been misnamed.

Journalism’s amour propre had overridden a clear-eyed assessment of what exactly the paper really was. Only then would it be fully apparent that it always should have been called the “adpaper.” When the corporation and the “Mad Men” who worked for it spied the Internet and saw how conveniently it gathered audiences and what you could learn about their lives, preferences, and most intimate buying habits, the ways you could slice and dice demographics and sidle up to potential customers just behind the ever-present screen, the ad began to flee print for the online world. It was then, of course, that papers (as well as magazines) —left with overworked, ever-smaller staffs, evaporating funding, and the ad-less news—began to shudder, shrink, and in some cases collapse (as they might not have done if the news had been what fled).

New York still has four dailies (Murdoch’s Post, the Daily News, the New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal). However, in recent years, many two-paper towns like Denver and Seattle morphed into far shakier one-paper towns as papers like the Rocky Mountain News and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer passed out of existence (or into only digital existence). Meanwhile, the Detroit News and Detroit Free Press went over to a three-day-a-week home delivery print edition, and the Times Picayune of New Orleans went down to a three-day-a-week schedule (before returning as a four-day Picayune and a three-day-a-week tabloid in 2013). The Christian Science Monitor stopped publishing a weekday paper altogether. And so it went. In those years, newspaper advertising took a terrible hit, circulation declined, sometimes precipitously, and bankruptcies were the order of the day.

The least self-supporting sections like book reviews simply evaporated and in the one place of significance that a book review remained, the New York Times, shrank. Sunday magazines shriveled up. Billionaires began to buy papers at bargain-basement prices as, in essence, vanity projects. Jobs and staffs were radically cut (as were the TV versions of the same so that, for example, if you tune in to NBC’s Nightly News with Brian Williams, you often have the feeling that the estimable Richard Engel, with the job title of chief foreign correspondent, is the only “foreign correspondent” still on the job, flown eternally from hot spot to hot spot around the globe).

No question about it, if you were an established reporter of a certain age or anyone who worked in a newsroom, this was proving to be the aluminum age of journalism. Your job might be in jeopardy, along with maybe your pension, too. In these years, stunned by what was suddenly happening to them, the management of papers stood for a time frozen in place like the proverbial deer in the headlights as the voicey-ness of the Internet broke over them, turning their op-ed pages into the grey sisters of the reading world. Then, in a blinding rush to save what could be saved, recapture the missing ad, or find any other path to a new model of profitability from digital advertising (disappointing) to pay walls (a mixed bag), papers rushed online. In the process, they doubled the work of the remaining journalists and editors, who were now to service both the new newspaper and the old.

The Worst of Times, the Best of Times

In so many ways, it’s been, and continues to be, a sad, even horrific, tale of loss. (A similar tale of woe involves the printed book. It’s only advantage: there were no ads to flee the premises, but it suffered nonetheless—already largely crowded out of the newspaper as a non-revenue producer and out of consciousness by a blitz of new ways of reading and being entertained. And I say that as someone who has spent most of his life as an editor of print books.) The keening and mourning about the fall of print journalism has gone on for years. It’s a development that represents—depending on who’s telling the story—the end of an age, the fall of all standards, or the loss of civic spirit and the sort of investigative coverage that might keep a few more politicians and corporate heads honest, and so forth and so on.

Let’s admit that the sins of the Internet are legion and well-known: the massive programs of government surveillance it enables; the corporate surveillance it ensures; the loss of privacy it encourages; the flamers and trolls it births; the conspiracy theorists, angry men, and strange characters to whom it gives a seemingly endless moment in the sun; and the way, among other things, it tends to sort like and like together in a self-reinforcing loop of opinion. Yes, yes, it’s all true, all unnerving, all terrible.

Let’s admit that the sins of the Internet are legion and well-known: the massive programs of government surveillance it enables; the corporate surveillance it ensures; the loss of privacy it encourages; the flamers and trolls it births; the conspiracy theorists, angry men, and strange characters to whom it gives a seemingly endless moment in the sun; and the way, among other things, it tends to sort like and like together in a self-reinforcing loop of opinion. Yes, yes, it’s all true, all unnerving, all terrible.

As the editor of TomDispatch.com, I’ve spent the last decade-plus plunged into just that world, often with people half my age or younger. I don’t tweet. I don’t have a Kindle or the equivalent. I don’t even have a smart phone or a tablet of any sort. When something—anything—goes wrong with my computer I feel like a doomed figure in an alien universe, wish for the last machine I understood (a typewriter), and then throw myself on the mercy of my daughter.

I’ve been overwhelmed, especially at the height of the Bush years, by cookie-cutter hate email—sometimes scores or hundreds of them at a time—of a sort that would make your skin crawl. I’ve been threatened. I’ve repeatedly received “critical” (and abusive) emails, blasts of red hot anger that would startle anyone, because the Internet, so my experience tells me, loosens inhibitions, wipes out taboos, and encourages a sense of anonymity that in the older world of print, letters, or face-to-face meetings would have been far less likely to take center stage. I’ve seen plenty that’s disturbed me. So you’d think, given my age, my background, and my present life, that I, too, might be in mourning for everything that’s going, going, gone, everything we’ve lost.

But I have to admit it: I have another feeling that, at a purely personal level, outweighs all of the above. In terms of journalism, of expression, of voice, of fine reporting and superb writing, of a range of news, thoughts, views, perspectives, and opinions about places, worlds, and phenomena that I wouldn’t otherwise have known about, there has never been an experimental moment like this. I’m in awe. Despite everything, despite every malign purpose to which the Internet is being put, I consider it a wonder of our age. Yes, perhaps it is the age from hell for traditional reporters (and editors) working double-time, online and off, for newspapers that are crumbling, but for readers, can there be any doubt that now, not the 1840s or the 1930s or the 1960s, is the golden age of journalism?

Think of it as the upbeat twin of NSA surveillance. Just as the NSA can reach anyone, so in a different sense can you. Which also means, if you’re a website, anyone can, at least theoretically, find and read you. (And in my experience, I’m often amazed at who can and does!) And you, the reader, have in remarkable profusion the finest writing on the planet at your fingertips. You can read around the world almost without limit, follow your favorite writers to the ends of the Earth.

The problem of this moment isn’t too little. It’s not a collapsing world. It’s way too much. These days, in a way that was never previously imaginable, it’s possible to drown in provocative and illuminating writing and reporting, framing and opining. In fact, I challenge you in 2014, whatever the subject and whatever your expertise, simply to keep up.

The Rise of the Reader

In the “golden age of journalism,” here’s what I could once do. In the 1960s and early 1970s, I read the New York Times (as I still do in print daily), various magazines ranging from the New Yorker and Ramparts to “underground” papers like the Great Speckled Bird when they happened to fall into my hands, and I.F. Stone’s Weekly (to which I subscribed), as well as James Ridgeway and Andrew Kopkind’s Hard Times, among other publications of the moment. Somewhere in those years or thereafter, I also subscribed to a once-a-week paper that had the best of the Guardian, the Washington Post, and Le Monde in it. For the time, that covered a fair amount of ground.

Still, the limits of that “golden” moment couldn’t be more obvious now. Today, after all, if I care to, I can read online every word of the Guardian, the Washington Post, and Le Monde (though my French is way too rusty to tackle it). And that’s every single day—and that, in turn, is nothing.

It’s all out there for you. Most of the major dailies and magazines of the globe, trade publications, propaganda outfits, Pentagon handouts, the voiciest of blogs, specialist websites, the websites of individual experts with a great deal to say, websites, in fact, for just about anyone from historians, theologians, and philosophers to techies, book lovers, and yes, those fascinated with journalism. You can read your way through the American press and the world press. You can read whole papers as their editors put them together or—at least in your mind—you can become the editor of your own op-ed page every day of the week, three times, six times a day if you like (and odds are that it will be more interesting to you, and perhaps others, than the op-ed offerings of any specific paper you might care to mention).

You can essentially curate your own newspaper (or magazine) once a day, twice a day, six times a day. Or—a particular blessing in the present ocean of words—you can rely on a new set of people out there who have superb collection and curating abilities, as well as fascinating editorial eyes. I’m talking about teams of people at what I like to call “riot sites”—for the wild profusion of headlines they sport—like Antiwar.com (where no story worth reading about conflict on our planet seems to go unnoticed) or Real Clear Politics (Real Clear World/Technology/Energy/etc., etc., etc.). You can subscribe to an almost endless range of curated online newsletters targeted to specific subjects, like the “morning brief” that comes to me every weekday filled with recommended pieces on cyberwar, terrorism, surveillance, and the like from the Center on National Security at Fordham Law School. And I’m not even mentioning the online versions of your favorite print magazine, or purely online magazines like Salon.com, or the many websites I visit like Truthout, Alternet, Commondreams, and Truthdig with their own pieces and picks. And in mentioning all of this, I’m barely scratching the surface of the world of writing that interests me.

There has, in fact, never been a DIY moment like this when it comes to journalism and coverage of the world. Period. For the first time in history, you and I have been put in the position of the newspaper editor. We’re no longer simply passive readers at the mercy of someone else’s idea of how to “cover” or organize this planet and its many moving parts. To one degree or another, to the extent that any of us have the time, curiosity, or energy, all of us can have a hand in shaping, reimagining, and understanding our world in new ways.

Yes, it is a journalistic universe from hell, a genuine nightmare; and yet, for a reader, it’s also an experimental world, something thrillingly, unexpectedly new under the sun. For that reader, a strangely democratic and egalitarian Era of the Word has emerged. It’s chaotic; it’s too much; and make no mistake, it’s also an unstable brew likely to morph into god knows what. Still, perhaps someday, amid its inanities and horrors, it will also be remembered, at least for a brief historical moment, as a golden age of the reader, a time when all the words you could ever have needed were freely offered up for you to curate as you wish. Don’t dismiss it. Don’t forget it.

Tom Engelhardt, a co-founder of the American Empire Project and author of The United States of Fear as well as a history of the Cold War, The End of Victory Culture, runs the Nation Institute’s TomDispatch.com. His latest book, co-authored with Nick Turse, is Terminator Planet: The First History of Drone Warfare, 2001-2050.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook or Tumblr. Check out the newest Dispatch Book, Ann Jones’s They Were Soldiers: How the Wounded Return From America’s Wars—The Untold Story. To stay on top of important articles like these, sign up to receive the latest updates from TomDispatch.com here.