<a href="http://www.talibkweli.com/photos/">Talib Kweli</a>/TalibKweli.com

Earlier this summer, when George Zimmerman was acquitted in the shooting death of Trayvon Martin, there were marches across the country. But the protests largely faded out, folding in on themselves before they had a chance to create any lasting change. One place that isn’t true is Florida, where a group calling itself the Dream Defenders took over the state capitol building, and called upon GOP Gov. Rick Scott to support the Trayvon Martin Act. The bill was an attempt to address racial profiling, the state’s controversial Stand Your Ground law, and zero-tolerance policies in schools that funnel kids into the criminal-justice system.

The Dream Defenders were able to gather a lot of national and high-profile support. Among the bigger names who turned out to support their cause was the Brooklyn-based rapper Talib Kweli, among the most enduring and successful “conscious” hip-hop artists of his generation. I caught up with Kweli last week for a chat that ranged from his new album (Prisoner of Conscious), to stop-and-frisk, feminism, and homosexuality in the hip-hop community.

Mother Jones: What made you want to go to Florida to support the Dream Defenders?

Talib Kweli: Harry Belafonte hit me to the Dream Defenders and I liked what they were about. When I asked them how I could help their movement, they said, “You can help by coming down here; you can tweet.” But I was like, “That’s easy, what else can I do?” What I like about Dream Defenders is they’re taking all the fly shit from activism—they’re taking the right energy from civil rights, from black power, from Occupy Wall Street, all these movements, the Arab Spring. They’re not protesting, they’re not demonstrating; they’re just coming with a plan for action and they’re not going anywhere until the governor addresses their plan.

MJ: After the Zimmerman verdict, some artists said they would boycott Florida. You said you wouldn’t. Can you talk about that?

TK: I support the idea that artists have to make a stand. I’m with that—you’re putting the discussion on the table and you’re letting people know. You’re being brave as an artist and responsible to the community. Stevie Wonder saying he’s going to boycott Florida—that’s one strategy. I just don’t necessarily see that as a strategy that I need to employ. Dream Defenders are mostly students. They can’t afford to boycott Florida. So I want to support them in their efforts.

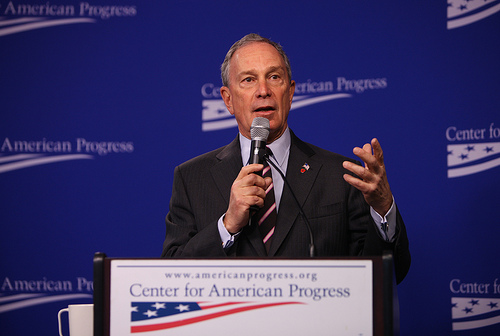

MJ: What are your thoughts on the recent court ruling that New York City’s stop-and-frisk policies are tantamount to racial profiling—and the fact that Mayor Michael Bloomberg said the city would appeal?

TK: He also said that if it was is his son, he might feel different. Bloomberg is a sensible guy. He’s just privileged. He’s a goddamn billionaire, and he or his family members have never had to deal with anything as remotely degrading as stop and frisk. So he has no point of reference.

MJ: New York City Police Commissioner Ray Kelly said people in minority communities want more stop and frisk.

TK: That’s all propaganda and it’s bullshit. No one likes to be treated like that. For him to make that statement is ignorant. What it’s saying is that because you’re poor, because you live in a neighborhood that deals with oppressed conditions, you deserve to be treated like a criminal. In our Constitution it says you have the right to live without illegal search and seizure. What else is stop and frisk? These neighborhoods are unsafe not because there’s not enough cops illegally frisking people. They’re not safe because of economic conditions. They’re not safe because of all types of things in the government that people like Bloomberg and Ray Kelly should be looking to fix instead of randomly searching kids in the hood. If you go to a college campus and you do stop and frisk, you’re going to find a lot of drugs there, too.

MJ: Do you see any connection between this debate and the one over the NSA snooping?

TK: Well, I think the biggest problem in our country is mass incarceration and the prison-industrial complex. From the Rockefeller drug laws to stand your ground to stop and frisk, all these are pointing people, especially and disproportionately black and brown people, towards the criminal-justice system. It’s depleting whole generations of people. We send young white boys to the Army, we’re sending young black boys to the prisons. And you have people at the top who don’t have to deal with any of that degradation getting rich off of this.

MJ: What drives your activism?

TK: It’s where I’m from. I cannot do what I do if it’s not for the family or the community. So when you have a voice and a platform and you know better, it becomes your moral obligation to support that community. And by extension, you’re supporting your family.

MJ: So how is Prisoner of Conscious being received?

TK: It’s going good. I still have another two or three videos in the can to drop. It’s an album that people are discovering at their own pace. I’m not an artist that has a big, huge radio record that’s going to be on BET. I’m not, at this point, gunning for like, “Oh, I’m gonna kill them in the first week.” But as people slowly discover the album they realize it’s better than a lot of what they’ve been listening to all year.

[Here’s the opening track, Human Mic, released last week.]

MJ: And you’ve been touring around the new album.

TK: I tour whether I have album out or not. I tour more than any other hip-hop artist.

MJ: Should we expect another album soon from Black Star, your project with Mos Def?

TK: Probably not.

MJ: You recently did a video for the Kinsey Collection called Untold Stories. It’s interesting because you’re telling this powerful story and then we find out at the end it’s sponsored by a bank. Can you talk about that?

TK: I guess they’re sponsored by Wells Fargo. Wells Fargo ran with it and made it a part of their campaign, which got a lot of my fans upset. They’re like, “Why are you working with Wells Fargo?” Your name is going to be attached to and associated with things that you don’t necessarily agree with it if you’re partnering with people sometimes. But I think Wells Fargo, just like all the rest of the banks, have a very clear recorded history of taking advantage of people, and I encourage people to take their money out of the banks altogether. When Occupy Wall Street happened, I took my money out of Citibank. I already had problems with all the banks—Citibank, Bank of America—but I was kind of just too lazy to take my money out until I saw how Citibank responded to Occupy Wall Street. I haven’t fucked with big banks since then. As an artist, people are going to use your name and your brand for all types of things.

MJ: Switching gears, can you reflect on hip-hop’s general attitude toward homosexuality and equality?

TK: Homosexuality in hip-hop is an extension of homosexuality in the black community. The black community is very, very conservative when it comes to homosexuality, and I don’t mean conservative in the good way, like we’re saving money. I mean very intolerant. That’s how it’s always been. I do see a new generation, partly because of the internet and technology, embracing it. I see young black boys, young black women in the hood embracing homosexuality in ways they never would’ve when I was younger. When I was a teenager, the way some of these kids out here be actively gay, it would have been ridiculed in the hood. And now the hood is a bit more accepting. Begrudgingly accepting, but definitely more accepting than 20 years ago when I was a little kid.

That doesn’t mean that anybody should stop fighting for equality just because people are begrudgingly a little more accepting. Now people won’t beat you up; they might just talk behind your back.

But as far as hip-hop, it’s real simple. There just needs to be a gay rapper—he doesn’t have to be flamboyant, just a rapper who identifies as gay—who’s better than everybody. Unfortunately hip-hop is so competitive that in order for fringe groups to get in, you gotta be better than whoever’s the best. So before Eminem, the idea that there would be a white rapper that anybody would really check for was fantastic or amazing or impossible. You had people like 3rd Bass and other people came through, and people respected them for their dedication to hip-hop. But people didn’t really take white rappers seriously until Eminem, because he was better than everybody. Like female emcees, you need to be like Lauryn Hill or Nicki Minaj or killing everything before somebody takes you seriously.

MJ: Can you talk about what happened when Crunk Feminist Collective accused you of not being a real ally for women? [He responded in detail at the time.]

TK: First of all, Crunk Feminist Collective, I think, is a noble endeavor, and any group of young women coming together to uplift women, especially being run by women of color, I have no choice but to support that. But they’re dead wrong on me. I support them whether they’re wrong on me or not because they’re needed.

The thing is, allies is people who are friends, people you can rely on in the struggle. You’re not always going to agree with your allies. For instance, Stevie Wonder I feel like is my ally when it comes to this Florida situation, but I don’t agree with his strategy. That doesn’t mean he isn’t an ally.

That’s the same way I feel about Crunk Feminists. Here you have a bunch of bloggers who are not even quoting any feminists’ works who are telling me what I can do better when I’ve been doing this as my life’s work while y’all still in college! What are you talking about? And their criticism was of the idea that we should approach people like Rick Ross and Lil’ Wayne with love when they have lyrics that we don’t like, as opposed to approaching them with hate. That’s their issue: How dare I say I approach Rick Ross with love! But you know, the founder of Crunk Feminists is a Christian. If you claim to be a Christian, but then you attack somebody for saying you should approach a problem with love, you’re not being a true Christian. But as far as female emcees, I’ve got a song on my new album called “A State of Grace,” which is about a young woman who has just basically given up listening to hip-hop. She’s tired of being called a bitch and a ho; she went to her favorite rapper’s concert and he let her backstage—she didn’t let him get it, he called her a bitch, and she just has negative experience with hip-hop.

It’s just a story. It’s something that I see young women going through. And to be honest with you, that whole exchange with Crunk Feminist actually made me write the song because I realize there’s a lot of young women out there so hurt by the misogynistic images in hip-hop they paint it with such a broad brush stroke that they think anybody that defends hip-hop is defending misogyny.

MJ: Where do you think progressive hip-hop artists fall into the broader scheme of mass media hip-hop nowadays?

TK: I try to count the blessings rather than the problems. On the hip-hop charts, you have J. Cole, you have Macklemore and Ryan Lewis three, four times in the top 10. You got Kendrick Lamar. I could go on. There are conscious elements all through pop music. Macklemore, Ryan Lewis are the best example; they made a completely conscious, underground hip-hop, indie album. It doesn’t get any more underground, conscious or indie than Macklemore, Ryan Lewis, but because they got a couple of really big pop hits, actually some of the biggest pop hits that hip-hop has ever seen, people are missing that part of their story. People are not counting that blessing.