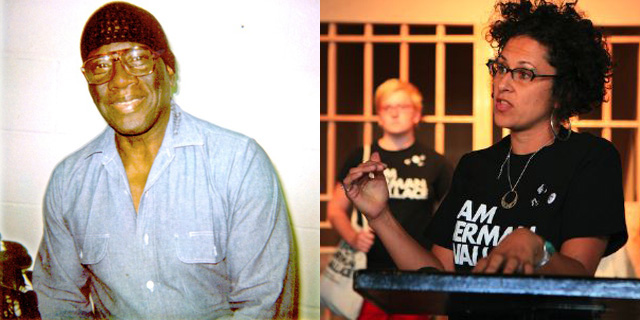

Herman Wallace and Jackie SumellLeft: Courtesy of Jackie Sumell, Right: Courtesy of N. Krebill

New Orleans artist Jackie Sumell has made a career out of building a house for a client who may never live there. There are a few other hitches: He can’t pay her. He’s not great at visualizing big spaces. His demands are at once idiosyncratic and utterly ordinary: a bear rug and mirrored ceilings, a garden and a pool. He’s very slow on correspondence. But for Sumell, it’s deeply rewarding work, emotionally if not financially. “I have an amazing life because of this project,” she says.

Sumell’s client is Herman Wallace, a member of the inmate crew known as the Angola 3 who has been held in solitary confinement for 41 years and counting, for a conviction based on highly questionable evidence. (That included witness testimony from jailhouse informants who had been promised special privileges, including two who have since recanted and one who was legally blind.)

Sumell is one of Herman’s longest-standing pen pals, and guided by his vision—sketched in hundreds of letters over the past 12 years—she is building his dream digs. Their project is the subject of Herman’s House, a documentary premiering Monday night on PBS.

The story has taken on a new urgency. In June, Wallace was diagnosed with an aggressive liver cancer. The prognosis is grave, and the activists who have fought for his cause for decades—Sumell, Wallace’s sister, Amnesty International, and many more—are mobilizing to urge his release. For them, the film’s premiere has new magnitude: What began as a work of art and activism has, for better or worse, become Wallace’s only lifeline to the outside.

“I never thought this would become Herman’s only way to get out of prison,” Sumell told me recently. But that’s how she sees it now.

When the project began back in 2001, Sumell was working as an environmental organizer in San Francisco. She had little interest in the prison system and no idea who Wallace was. But she had decided to go to a lecture by another Angola 3 member, Robert King, who had just been released, his conviction overturned after 29 years in the hole. Sumell recalls riding to the event on her bicycle and getting into a shouting match on the way with a motorist who cut her off.

“And then I went into this lecture and this man spoke about being in a six-foot-by-nine-foot cell for 29 years without any indication of anger. I was like: Oh, shit. I have something to learn from that man. He’s been able to channel so much trauma into these constructive mechanisms. Whereas I get cut off on my bicycle on Market Street and I’m ready to throw down.”

Inspired by King’s lecture, Sumell wrote to Wallace for the first time. As a part of that, she duct-taped a disposable camera to her arm and set her watch to go off every hour, on the hour. At each alarm, she took a photo of whatever was in front of her—her socks, her laptop, the Golden Gate bridge.

“I had never written anyone in prison before. I didn’t know what to say or what to write,” Sumell says. “This was an unedited view of 24 hours of my life.”

When Wallace got her package he thought initially that the photos were junk. “I’m wondering, what in the hell is she sending me these pictures for?” he recalls in the film. “But then when I read the letter, it had significance. It was something she was doing to say: ‘I would show you how things were with me out here, in comparison with what life is for you.'”

Two years into their correspondence, Sumell had started an MFA program at Stanford. In an architecture class she got an assignment that called for interviewing faculty members about their homes, but instead Sumell wrote to Wallace: “What kind of house does a man who has lived in a six-foot-by-nine-foot box for over 30 years dream of?”

“I imagined it would provide some distraction, some play,” she recalls. “That it would give him the opportunity to leave his surroundings through his imagination.”

He began with a few details: a swimming pool, a garden with flowers year round—gardenias, carnations, and tulips. Over the next five years of letters, drawings, and revisions, a complete home was born, planned down to the color of the kitchen walls (yellow), the size of the bed (king), and the dimensions of the hot tub (six feet by nine feet, for obvious reasons).

“This is definitely Herman’s house. I’ve never rejected any of his designs,” Sumell says. “I mean, I’d tease him. I’d be like, ‘Really? You want shag carpets? It’s not the ’70s anymore.'” (Wallace was moved to solitary in 1972.)

The documentary suggests that Sumell was precisely the kind of person Wallace needed to rally to his cause: someone with big passion and little inhibition or fear. Director Anghad Balla illuminates Sumell’s activist backstory, from debating solitary confinement on a New Orleans sidewalk, to protesting President Bush’s policies in the early aughts, to being the first girl in the history of Long Island, New York, to play competitive tackle football.

“Nobody wanted to take me to the prom,” Sumell laughs, “I was the girl who played football! But that’s where I got my feet wet in terms of being an activist. Where I realized that if I believed in something and went towards it, that I would be rewarded…I realized I could continue living my life that way.”

As she and Herman corresponded, Sumell drew up blueprints of the home, and eventually built wooden models and produced CAD images—3-D views of the home that observers can navigate through on a screen. All this became “The House That Herman Built“—an art installation that, as of this writing, has been shown in nearly a dozen countries.

For the exhibit, Sumell also built a full-scale model of Wallace’s actual home—the solitary cell he’s confined to 23 hours a day—and made it open for visitors to experience for themselves.

Almost all of Sumell’s stories about reactions to the exhibit involve people crying. There’s the French curator who couldn’t talk about it without tearing up. The German woman she found weeping in a gallery corner. The differences between American exhibit-goers and those from elsewhere, whose countries don’t have anything approaching America’s scale of incarceration.

This was not her initial intention: “This started off just as an exchange between Herman and I,” Sumell says. “But I’ve seen that it’s actually powerful in terms of interrupting what people are willing to care about. Because you know, there’s so much that’s miserable in the world. There’s climate change, children dying of starvation. And on top of that I’m asking people to care about this prisoner who’s in solitary, and they’re like, ‘I’m overwhelmed with misery.’ But when I start talking about how he’s dreaming of a swimming pool or how he wants mirrored ceilings or gardens, people have more time to invest.”

For years, Sumell has been raising money to build the home in New Orleans, and looking for a suitable piece of land. But with Herman’s diagnosis, Sumell’s priorities have shifted to trying to get him released quickly.

“I knew he wasn’t immortal, but I never thought he would die inside the prison,” she says. “Herman has had a powerful effect on my life. I basically live my life the way I do because of him. My greatest fear is that he will be alone and suffering in the prison. But the Department of Corrections has the power to not let that happen. It’s a power we will fight for.”