Karen RussellMichael Lionstar

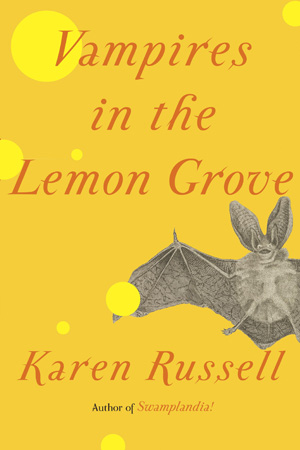

Women who morph into furred silkworms enslaved by the Japanese empire; vampires that rely on the “soothing blankness” of lemons to blot out their bloodlust; hoarder seagulls that stash scraps from the future in trees. Such are the strange creatures in Karen Russell’s suspenseful new collection, Vampires in the Lemon Grove, which comes out next week.

Russell, 31, first made waves with the short-story collection St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised By Wolves, unleashed in 2006 as she graduated from Columbia’s MFA program. Her 2011 novel Swamplandia!, about a family running a threadbare alligator theme park in the Everglades, was a Pulitzer finalist last year (though no book received enough votes to win). And as her new collection hits bookstore shelves, Russell is already hard at work on her next novel, set in the Dust Bowl era. Though she was pretty tight-lipped about it, her story “Proving Up” in Vampires hints at the spooky Americana she’s capable of.

In our early morning chat, Russell recalled Flannery O’Connor’s reading of Kafka’s Metamorphosis: “The truth is not distorted here, but rather a certain distortion is used to get to the truth.” O’Connor may as well have been talking about Russell, whose tales flirt with the fantastical, but are rooted in darker realities—loss of innocence, PTSD, all-consuming ambition. Even as she transforms the everyday into a wriggling bestiary, replete with colorful hallucinations and ghosts, her most haunting bits rely on the depiction of human impulses. I asked a “coffee’d up” Russell about the wellspring of her imagination, her swampy backyard, and breaking into the literary treehouse.

Mother Jones: When did you start to think seriously about writing fiction?

Karen Russell: I took a fiction-writing workshop my sophomore year at Northwestern, and I hadn’t yet read Junot Díaz or George Saunders, Flannery O’Connor. There was something so attractive about those voices. I heard about an [MFA program], and it just sounded like this magic thing, fairy-tale style—that there was a school you could go to exclusively for the thing you loved. I moved to New York with the derangement of love. I was writing all these terrible stories, but I had never been happier.

MJ: So getting an MFA was worthwhile?

KR: Almost because it was such a weird, controversial decision. Financially, it’s not a wise decision; I think most people in my MFA felt that. They became really serious about it because they had gone and done this crazy thing.

MJ: You’ve talked about being a slow writer, getting fixated at the sentence level. How do you know, then, when to scrap a story?

KR: I have friends who are capable of writing a very rough draft and then going back and embroidering—they’re sort of the cathedral builders of fiction. I never really know what I’m doing, and all my pleasure’s on the level of the line. It’s a weird way to move forward. It’s kind of like a way to caterpillar your way through these great woods. The best ones, whatever I feel like I’m writing about, some other secret thing will begin to come into focus.

MJ: You have a knack for making the everyday seem remarkable or surreal. Did your instructors try to rein in your wilder instincts?

KR: Yes. That was a big struggle, trying to get those ratios right. The first stories I was writing had a deranged lumberjack named Flapjack, or I had albino parrots. I remember getting advice, which for me as a young writer was maybe the wrong advice:, one of my Northwestern professors said, “Why don’t you try to have some adult characters?” Any story I tried to write at that point in a realist mode or a mock Carver mode was so terrible, overly lyrical.

I got one good piece of advice from [author and associate professor] Ben Marcus in one of my Columbia workshops: If you’re gonna do something weird, just have one thing be weird. Like a version of “blue doesn’t show on blue.” You want to have it feel real enough to a reader so that they care about what’s happening within the confines of that story—you don’t want the surreal elements to totally remove the story from the world of consequence.

MJ: So, how do feed your imagination?

KR: [Laughs.] Pharmaceuticals!

MJ: Because when you’re a kid, it’s bubbling out all the time, but as we get older a lot of things come in the way. So I’m curious how you keep yours so alive.

KR: The folks I read as a kid really set me up. I owe a huge debt to Ray Bradbury and Madeleine L’Engle. And Florida, I mean, you don’t have to look far. It’s like Carl Hiaasen, a writer I like a lot—he’s always talking about how the headlines are so much stranger than anything you could come up with. I was just down there and there were all these posters all over Miami that say, “Wanted: Giant African Snail.” Or there was like a plague of pythons loose. Why even bother writing fiction? My backyard was replete with madness, it just grew indigenously in South Florida.

MJ: What do you think poses the biggest threat to our imaginations?

KR: People really get myopic as they get older. We’re not a culture that encourages dreaming or distraction. We’re not ever good at just being. I remember reading some Adrienne Rich quote where she talks about how important it was just to watch bubbles rise in a glass.

I think there’s this horrible image of the artist as this complete ego monster dreamer. I even find that with like artist residencies, you know? They’re like, “Oh, you’ve got to remove yourself to the magic mountain.” I do think there’s something when you have an unbroken day, and it feels like you and your attention can just be together like birds again and you can actually think and dream a little.

MJ: Swamplandia! takes place in the Everglades, near where you grew up, but many of the subjects in Vampires in the Lemon Grove seem very otherworldly. How were they spawned of your experiences?

KR: Even some of the wilder stories, like the story about this tailgater in the Antarctic—what felt familiar to me is that my own brother was a huge hockey fan in Miami. I can’t even tell you all the ways that it’s perverse, sort of like the Jamaican bobsled team, and the optimism and delusion involved. I’ve loved those narratives of survival and the doomed quest. Even, gosh, the presidents reincarnated as horses, that’s definitely not autobiographical in any sense, but sometimes they just start out as these really dumb ideas. I was thinking: Why should the afterlife make any more sense than this life?

MJ: Why horses?

KR: Exactly! How totally absurd. What a tumble, from the White House to a Kentucky stable. I wanted something completely baffling, to them as well. A mystery that wasn’t going to resolve.

MJ: Did you spend any of the past election year imagining how the politicians on TV might reincarnate?

KR: I can easily imagine Mitt Romney in that stable, actually. For me, whatever humor there is in that story came from the contrast between the high oratorical, self-important speech-making impulse, and being stuck in this animal body. Just this fly-covered, sweaty, form.

MJ: What kind of horse would Mitt be?

KR: Don’t you think he’d be some kind of thoroughbred with a really fancy lineage that he would trot out a lot? He’d have racehorse ancestors going back to the revolutionary days that he would find some way to keep mentioning. (Russell emails me later to suggest a Shetland pony.)

MJ: The frontier figures pretty prominently in your writing—the Great Plains, the homesteading era, unexplored parts of the Everglades, the Antarctic. Where have you personally confronted the frontier?

KR: People will say the Everglades are like a curated, museum version of what they were, but that place feels genuinely ancient and foreign to me every time I go. And it’s such a stark frontier, because you enter this strip mall, faceless, Burger King world, and then you’re in the swamp. The frontier narratives are so interesting because they push humans into the frontiers of their personalities, you know? I think it really is true that strange things happen in frontiers that far out.

MJ: You seem kind of concerned with how events can morph into myths upon the recounting and how those myths later affect people’s realities. Your vampire character Clyde thinks at one point, “You small mortals don’t realize the power of your stories.” Can you talk about this?

KR: I was thinking about how things pass from present time into history into memory, and then into myth—and the afterlife of an event in a body, which can be lifelong. That must be a personal obsession, because it kind of kept driving along the stories in this new collection. Like these hauntings. In, “The New Veteran,” the veteran hasn’t figured out a way to tell the story of what happened to him abroad and is really haunted by the loss of his friend.

In a really different way, I thought about the movement in Swamplandia! as being of that same trajectory. So this kid gets completely enmeshed with all of her family myths. She’s like, “We’re alligator wrestlers. We live in an Edenic park. My mom is the most famous and most beautiful. My sister talks to ghosts.” There all these things she accepts really uncritically. It’s not like you can do without stories, right? She just figures out a way to get herself out of the swamp by really consciously telling another kind of story.

MO: Do you find yourself distrusting history texts, or the media? I get a sense of that.

KR: So much trouble is created by a completely uncritical faith. In even really beautiful myths, the underdog can triumph. Certainly that’s true sometimes, but to tell the story where the underdog is the victor, sometimes you exclude other kinds of structural injustices, or you put all the emphasis on the individual and you’re not really looking at the forces that create underdogs. So I guess that’s a way of saying thank goodness we have historians and official histories, but you know, definitely it’s good to kind of look around corners and see who’s excluded or omitted. And I’m pretty pessimistic that you could ever tell a complete story. People are always operating in a blind spot. It’s a pretty partial vision that we have of our own motivations.

MO: How do you plan to do research for your next novel, set in the Dust Bowl era?

KR: I probably will just have to fly out to Oklahoma at some point and beg some ancient man named Wendell who’s in his nineties to ride me around his property.

MO: As a Pulitzer finalist last year, did you feel like you had been duped when they didn’t award the prize for fiction?

KR: There’s some part of me that’s still processing that situation like a boa constrictor, at a really slow rate. But there’s just no way for me not to be grateful to those nominating jurors; there’s something wonderfully validating about getting to be on a shortlist that includes David Foster Wallace and Denis Johnson. And I loathe and avoid controversy. So it was kind of interesting to briefly feel wrapped up in, you know, a controversy.

MO: I’m curious what being named a New Yorker “20 under 40” writer does for your career.

KR: Oh man, it’s all been amazing since then. Gold flooded in, celebrities started taking me out to lunch. It was all five star. My financial worries are done! No, you know, it’s funny, lists are always completely subjective, and fluke-y and strange, but I was really honored because I loved so many of the other writers on that first list that they did, like Junot Díaz and George Saunders and Antonya Nelson. That’s all kinda neat to get to be invited to that treehouse club. I mean it’s still a big struggle. You still deal with rejection and doubt, and none of that’s changed at all. One concrete difference is that now that when I go home for the holidays, my relatives seem relieved.