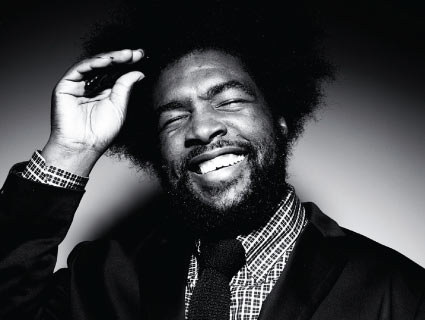

Backstage at Manhattan's Highline Ballroom on January 10.Jacob Blickenstaff

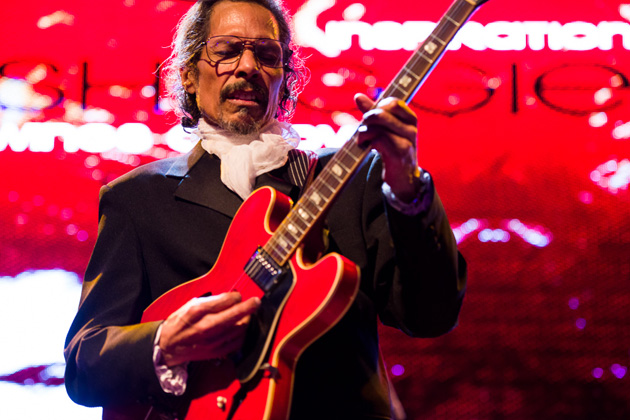

On a Thursday night the week before last, Shuggie Otis was at Highline Ballroom in New York City, headlining a preview for SummerStage (a free outdoor concert series). The diverse crowd consisted of hip-hop heads, wide-eyed indie rock fans, older blues fans, music biz cognoscenti, and everyone in between, all curious to see how Shuggie would sound after all this time. It had, after all, been 38 years since the 1974 release of Otis’ third and latest album, Inspiration Information. Since then, Shuggie kept a low public profile for decades, sporadically writing and recording his own music, and doing sessions and gigs with for his famous father. Still, his modest output kept bubbling up as samples in songs by acts from the Fat Boys to Outkast and Beyoncé—not to mention covers by the likes of Sharon Jones and the Dap Kings. But once the thumping eight-bar intro of ostinato bass and shifting chords from Inspiration Information‘s title track hit the Highline crowd’s senses, all was well and good.

Shuggie’s story has all the trappings of a “whatever happened to” tale. The prodigious progeny of R&B pioneer Johnny Otis (singer, multi-instrumentalist, talent scout, A&R man, producer, radio and television host), Shuggie grew up at the feet of musical legends. He recorded his first solo album, Here Comes Shuggie Otis, at 16 (following a “Super Session” album cut with Al Kooper at age 15). For his sophomore LP Freedom Flight, he penned the psych-funk nugget “Strawberry Letter 23” (which exploded into the national consciousness six years later when the Brothers Johnson turned it into a million-seller). At just 21, Shuggie realized his own autonomous musical vision with Inspiration Information. Just as things were starting to go well for him, Epic Records unceremoniously and simultaneously dumped both Shuggie and his dad from the label. Shuggie, preferring to be his own bandleader, turned down invitations to be a sideman for some of the biggest pop acts out there.

Without a record deal, he drifted from the spotlight, but his music continued to draw devotees who found something unique in Shuggie’s blending of funk, pop, blues, jazz, and electronic music into a vibrant personal world. Blues and soul connoisseurs shared tapes of his out-of print LPs, and pop and hip-hop producers began sampling the distinctive melodies and textures of his tunes. His last album was officially anointed “hip” via a 2001 reissue on David Byrne‘s Luaka Bop label, with new artwork and hyperbolic myth-fanning liner notes.

In April, Sony/Legacy will re-reissue Inspiration Information with bonus tracks from the original sessions, along with Wings of Love, a disc of previously unreleased music recorded between 1974 and 1990 (plus one live track from 2000). Now Shuggie finally has the opportunity to make up for lost time with an international tour booked, a hot new band, and plans to write and record brand new material. I caught up with the artist in advance of his New York City showcase to shoot some portraits and talk about where he’s been, and where he’s going.

Mother Jones: I read somewhere that you started in music really early—like at age two!

Shuggie Otis: No, no, I didn’t start at two. I got a drum set at the age of four. I wasn’t playing that well, just kind of banging around. I just wanted to play drums and my dad got me a set. I played for several years, but I wasn’t meant to be a drummer, I guess. I can play drums on my own things—obviously on some of my own records I play drums. But I didn’t start playing guitar until I was 11.

MJ: When did you start performing live with your father?

SO: When I was 12—and I played bass—at a club called Jazzville up in San Diego. I was supposed to play guitar. We had three guitar players in the band, but the bass player never showed up and LA is like two hours away so we had to get going. I was elected to play bass. So we picked up a bass—one of the other guitar players’ dad owned a music shop—and I played all night. We did three sets, and it was great. I like playing bass just as much as I like playing guitar.

MJ: Was there anything else you wanted to be when you grew up?

SO: Ha! I can’t think of anything else I wanted to be besides a musician, not really seriously, no.

MJ: You must have met an enormous number of legendary blues and R&B artists. Were there any you had a close connection with?

SO: I would say Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson. Pee Wee Crayton was a really nice cat. I went on tour with Cleanhead. We went to Asia, we got to know each other over there. We also toured the States. There’s others if I can think of them.

MJ: Probably too many to remember.

SO: Well I played with a lot of people. Like Joe Turner. We did some albums with Richard Berry, Louis Jordan, but these were just sessions. I met T-Bone Walker, I never toured with him but he was very friendly to me. And when he got ill we’d go see him—me and the guitar player and the singer we’d grab a couple of guitars and go play—because he had tuberculosis and he was staying in his place. I met BB King. He’s another one who was very nice to me.

MJ: He’s been quoted as saying that you were one of the best new guitarists he had heard at the time.

SO: I heard that recently, that he had said that in a magazine some years ago, and it surprised me. What a compliment!

MJ: When you were growing up and playing with your father, how did you balance the roles of bandleader and son? Was that difficult?

SO: No, I was always a good sideman. I understood my job. We would have our little beefs now and then, but it was never over music—just regular father and son stuff. I was always there, on stage, whether we were getting along or not. It’d be like one day we’re one place and the next day we’re getting along. Dad was kind of like that with a lot of people. But he was a good guy, deep down inside everybody really loved him. If something went wrong, usually people would come running back. He had a heart of gold.

MJ: Given your dad’s work as a talent scout, was he involved with trying to develop you as an artist when you started recording your own albums?

SO: Oh yeah! He was the producer of my first two albums. On the third album they pretty much let me have free reign. They just said go for it because, I assume, of “Strawberry Letter 23” on my second album, where I played all the instruments and used a drum machine. I wound up getting producing credits because, well, I produced it, you know. Basically dad bowed out at one point.

MJ: Was it your desire to start recording your own stuff, or was your father pushing to develop you as an artist?

SO: Oh, no. I was never pushed into the business. I wanted to play the guitar. When my dad found out I could play pretty good he took me into the studio one day. I did my first session for his label. We did quite a few sessions up there.

MJ: Your album Inspiration Information has earned many fans over the years who have a strong connection with the music. What do you think people hear in that album?

SO: I can’t really answer. Everybody has their own idea about what Inspiration Information is all about. Most people usually say that it’s different and that it still holds up.

MJ: Do you retain a strong personal connection to that album?

SO: I feel a strong connection with all my albums, especially the second two because I had more to do with the creative part.

MJ: Around the time you recorded Inspiration Information, Sly Stone and Stevie Wonder were producing their own work. Were they examples for you?

SO: I’ve always been a fan of Stevie Wonder, and Sly Stone a huge fan. All of his albums I pretty much have in my collection. We used to record at the same studio. They had four studios on one lot over at Columbia in Hollywood. Studio C was our favorite, so if we weren’t there then he was there. I’d see him every now and then. I didn’t meet him until just recently at a concert we did at the Mayan Theater. That was quite special.

MJ: You played most of the instruments on that album, and recorded it over the course of three years. What was your work process like?

SO: We started off in April of ’72 at Columbia Studios and we did a few tracks. Then we had to do a tour for the Johnny Otis Show that summer. So we did the tour and while we were in England, my father spoke to the Columbia people. Instead of a cash deal he wanted a studio built in the back of the house—and they went for it, so I finished the album there.

MJ: You were only 21 when that album came out. So what happened at that point that led you to stop releasing albums?

SO: Well, I didn’t have the power. I didn’t have the money to put out an album on my own. I was dropped from the company, along with my father, and what I heard was all the R&B and jazz artists were dropped at the same time for some strange reason. It didn’t faze me one bit. I thought I would get another record deal immediately. I went to so many record labels—name any one—and they all turned me down. For some reason I just got the thumbs down for years and years. It sounds like I’m making that up, but it’s true. I’m too serious about music and my creations to take just any kind of deal. There were a couple of companies that wanted to put me with a producer, and I said, “Well, I just produced my last album,” and I wasn’t about to go backwards.

Also, with the groups who had asked me to join them—like The Rolling Stones, Spirit, David Bowie, and Blood Sweat and Tears—I said no right away because I was way too much into my own thing. I didn’t want to be a sideman. My own style was coming out and I was into my own writing. I wrote that whole album, I arranged it all with pencil and paper. I did eventually do a lot of work with my father, but that was different. I was living at home; I wasn’t a starving musician. I wasn’t spoiled, but I wasn’t going to have some producer come in and tell me what to play.

MJ: That must have been frustrating at a time when Stevie Wonder was being allowed to produce his own albums.

SO: Yeah, he was doing it, and then Sly did his albums, so I kinda remember me being like the third person (that I remember) doing it, and I’m very thankful for that. But I wasn’t doing it because Stevie Wonder was doing it.

MJ: Right, I was just putting it in the context of the music business at the time.

SO: I never really got bitter about it. It became humorous to me. So I just said forget it. My life was going well without the music business. Maybe I’d let a year go by without sending anything out, then I’d go out again sending tapes and CDs here, there and everywhere—and then the same thing would happen all over again. It’s been happening since ’74. It sounds kinda crazy, but it’s true. That is just the way it went.

MJ: Your upcoming release consists of a reissue of Inspiration Information, plus a new CD, Wings of Love, with material recorded in the years since then.

SO: I’ve been doing all kinds of recording since then—a lot of stuff is still on the shelf. But I have my own label now, and we’re going to get started on a new album pretty soon. I’ve got a new band and I want to feature them, as well as doing some of the tracks myself. I’ll probably start most of them by myself, that’s the routine that I’m used to. We’re going to be performing songs off of Inspiration Information as well as some of the songs from Wings of Love. That’s old stuff too…but it’s good! I’m very proud of it.

MJ: Do you think there’s any kind of thread that runs through the “new” old material that you recorded since 1974?

SO: The common thread would be me, because I’m playing all the instruments on all of these things, except for some of the tracks that my brother plays drums on. Some of them I did shortly after the release of Inspiration Information so you can maybe hear some of that sound on the early tracks. When we go into the 8’0s it has more of a pop feel. But it’s what I wanted to do. I wasn’t trying to reach. See, that’s the thing with me, I never wanted to reach any particular crowd. I’m writing for myself. If I don’t like it I won’t play it for anybody.

MJ: I realized while listening to Inspiration Information that it is your first album without a single blues track on it, and maybe that was part of coming into your own music?

SO: Yeah, you’re right. I love the blues, don’t get me wrong. I’m not so much into doing traditional blues anymore except for in person. I find writing much more interesting outside a traditional style. I like to explore.

MJ: Do you start with bits of music, or a lyric?

SO: It goes both ways. Sometimes I’ll hear some music in my head or I’ll go to the piano and mess around and come up with a tune, or be on the guitar and come up with some chords—or I’ll come up with lines, or just some words, or just a sentence. It could be the title of a song. I do that all the time. I write titles of songs a lot. And sometimes I’ll end up writing a song that I don’t have a title for and I’ll say, “Oh, this goes with that title.” For instance in the song “Inspiration Information,” you don’t hear me say that anywhere. That just came to me one day. I don’t know why. And it became the name of the album.

MJ: I’ve got the lyrics here. It says, “Here’s a pencil pad, I’m going to spread some information.”

SO: Yeah.

MJ: So, uh, what’s a “snake-back situation”?

SO: [Laughs.] A sneak-back situation! That’s a good one.

MJ: Wait, it’s “sneak back”? That means a lot of people, including myself and Sharon Jones, who covered your song in 2009, got the opening lyrics wrong: “He had a rainy day, I’m in a snake-back situation.”

SO: Yeah. I’m in a sneak-back situation now. I mean I’m not sneaking back, I’m starting back, you know? Wait, my manager is correcting me, I’m storming back. I got a second wind. It’s like I fell in love with music all over again. And I never stopped. You know, there was this article that came out in Rolling Stone—I was 22 at the time—that said, “Shuggie Otis retired at the age of 22.” And I said, “Who the hell wrote this and where did they get this nonsense from?” It’s just strange. I went to my father one day and asked, “I wonder why he said that?” And he said, “Well, you did kind of quit.” Even he thought that. I said “I didn’t quit, I was out there trying to get record deals.” I’m not lying; I’ve got witnesses. Big ones, little ones, name a record company and I went there, more than once! I went to so many record companies it’s not even funny.

Click here for more music coverage from Mother Jones.