<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic.mhtml?id=66782641">olly</a>/Shutterstock

Two weeks ago, mere minutes after the American Society of Magazine Editors (ASME) nominations for its annual awards were announced, pointed tweets started ricocheting through the ranks of magazine writers and editors:

Someone tell me I’m misreading this: NO WOMEN nominated for ASMEs in Reporting, Features, Profiles, Essays or Columns? bit.ly/H6m1T1

— Liliana Segura (@LilianaSegura) April 3, 2012

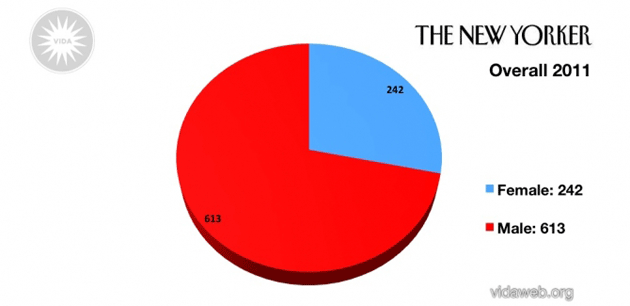

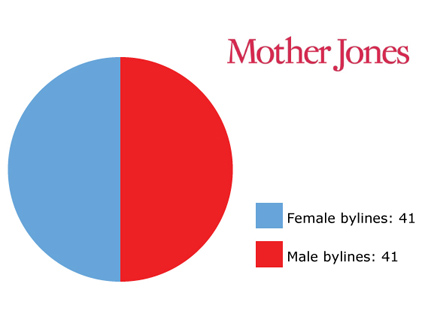

To many, the shutout of women in those categories was a perfect indicator of the byline gap that plagues magazine journalism—particularly when it comes to ambitious narrative reporting and nonfiction. It’s a subject we’ve been obsessed with for years (read more here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here), and one that got special attention when a group called VIDA began focusing on the problem among magazines known for fiction, book reviews, and literary non-fiction. The upshot: Some of the most prominent magazines in America had byline counts that continue to be discomfiting.

MoJo reporter Adam Weinstein had been at work on an interview with Erin Belieu, one of the founders of VIDA, when the outrage over the ASME nominations began. So he called her up to get her response (read the full interview here):

Not to denigrate the genuine accomplishments of the small number of women who were nominated, but it’s interesting that they’re acknowledged for what [GOOD magazine executive editor] Ann Friedman identifies as “service” writing—the vast majority of their nominated articles concerning “women’s issues”—on breast cancer, under-aged brides, women’s body image. These are all worthy subjects and the nominations are well deserved, but it does beg the question: Do women journalists only want to write about “women’s issues”? Or is that the only thing for which they’re commonly rewarded? Why is it that the nominated men wrote about such a variety of topics that don’t seem to be strictly defined by the equipment they sport from the waist down? A friend of mine defines this kind of intellectual segregation as the “tits and nether bits” ghetto, a place in which women only speak to other women. Meantime, men are allowed and encouraged to speak to whomever they want.

Our interview with Belieu prompted Sid Holt, the chief executive of ASME, to write expressing concern on a number of fronts. With his permission we’ve taken the exchange that ensued and boiled it down in a way that we hope provides additional perspective on the subject.

But first, you might ask, what are these ASME awards? Each year, ASME members (mostly editors-in-chief and creative directors, or their anointed stand-ins) select nominees for the industry’s top prizes, the “Ellies.” Hundreds of us gather in NYC to judge our peers. Holt—among his previous posts he was the EIC of Adweek and the managing editor at Rolling Stone—has the touchy task of herding all those cats and soothing all those egos. He does it very well.

Holt’s first concern was that those not familiar with the Ellies process might blame the judges.

I know that you know that the problem with the byline count in the awards lies with the bylines on the stories that are entered in the awards, but I think readers are more likely to conclude that a bunch of middle-aged white dudes are in cahoots to deny women writers their due. You know how unlikely that is, given the way the judging is organized, and you know that ASME has done everything short of telling judges not to just nominate the big boys so that women’s magazines, smaller magazines, magazines outside New York can get some props.

True! In the six years that we’ve served as judges, we’ve never seen anything to hint that gender bias in the judging process is at work. [More from Clara on this at The Awl.] If anything, it’s noted and bemoaned by judges that not enough stuff penned by women is submitted in certain categories.

Holt further points out that:

This year 118 of the 243 print judges were women, as were 8 of the 20 print judging leaders and 15 of the 32 judging leaders in all categories combined. As examples of the numbers in the reporting and writing categories, 4 of the 11 judges in Reporting and 9 of the 15 judges in Profile Writing were women.

Holt was also concerned that Belieu’s comments were a slight to women’s magazines. By way of background, readers should know that the ASME awards were rejiggered two years ago in part to better surface work done at women’s/shelter/lifestyle/mass-market magazines. Where once the “general excellence” categories were awarded by circulation size, now magazines are (sort of) grouped by competitive set. (This has created its own set of confusions, but that is for another day.)

Holt: I am acutely aware of the problems in magazine journalism—shortcomings that don’t stop at gender but encompass ethnicity and class—and I agree that the byline gap in the National Magazine Awards is indicative of a larger problem that deserves to be discussed. But what surprised me about the interview was Belieu’s apparent contempt for the millions of women who read service and lifestyle magazines. Her lack of understanding of what readers want is matched only by her ignorance of the historic importance of women’s-service magazines. Far from being what she calls a “‘tits and nether bits’ ghetto,” these carefully crafted magazines far outweigh in readership and influence many of the magazines that publish the kind of narrative journalism that Belieu evidently believes is the only kind of work worth talking about.

…Belieu bases her conclusions about the awards on nominations in 5 of 32 categories, underestimates the importance of the 27 other categories and disregards the history of the awards. Since Mother Jones was nominated just last year in Feature Writing for Mac McClelland’s “For Us Surrender Is Out of the Question,” you know that articles written by women are regularly nominated in the reporting and writing categories. Recent award winners in these categories include Katherine Boo, Anne Fadiman [x2], Sheri Fink, Vanessa Grigoriadis, Laura Hillenbrand, Elizabeth Kolbert, Katha Pollitt and Samantha Power, and last year’s nominations included Pamela Colloff’s second in Public Interest and Jane Mayer’s third in Reporting. [Eds: all these are fantastic pieces, though worth noting that some are almost a decade old.]

Holt goes on to talk about how Belieu doesn’t mention Public Interest—typically, classic investigative journalism—where 4 of the 5 nominees this year are women. Our reply:

Belieu was not among the originators of this criticism; the choice of categories addressed, and the failure to take note of the women nominated in the Public Interest category, should not be laid at her feet…Belieu’s opinions are of course her own, though we didn’t find them to be contemptuous of the enormous role of women’s magazines—what we read was simply frustration that the accomplishments of women in this area have not been fully translated to the broader industry.

Nowhere, including in this interview, have we seen anyone imply that the fault lies with ASME or its judges…The problem originates not with any bias in the judging, but with too few women getting assignments for the types of pieces that fall into those categories. Perhaps it is compounded by too few deserving pieces penned by women being put forward by ASME member pubs. More broadly, women are often pigeonholed into certain kinds of assignments, and they pigeonhole themselves.

You talk of “what readers want.” Here is some of the most fascinating terrain in this debate: Why is it that (most) men’s magazines consider ambitious reporting and storytelling to be essential to their brands, and women’s magazines don’t? Every woman we’ve ever met—including all the smart and wonderful women’s magazine editors we’ve met through ASME—wishes it were otherwise. We think Belieu speaks to this state of affairs quite eloquently.

Why is it that (most) men’s magazines consider ambitious reporting and storytelling to be essential to their brands, and women’s magazines don’t?ASME has ensured that the brilliant work done by women’s magazine has a chance to be properly honored. Bravo. But that doesn’t address the broader issue the critics raised.

The byline gap—in ASME nominations, and more generally—is a problem that has many causes, none of which will be addressed unless they are first acknowledged, discussed, debated.

Holt’s reply:

The judges are judging the magazines we have, not the magazines we wish we had. The problem with the awards that the byline disparity actually reveals is not that women writers are underrepresented, but that narrative journalism is over-represented—that 7 out of 20 categories for this kind of work is disproportionate to the categories allotted for, say, service journalism. The reason long-form journalism doesn’t have a place in women’s magazines is that the audiences are too big—it’s the same reason multiplexes show “The Hunger Games” and not “Bully.” The magazines that do publish it get away with it because their business models are different—which is another way of saying their circs are smaller.

We asked why he thought men’s magazines are more immune from those forces—or why size would be a limiting factor. (For example, ESPN the Magazine, at 2 million readers, is nearly as big as Glamour, O, or Redbook, but it publishes significantly more narrative journalism.) Holt’s reply:

We’re really talking about a handful of magazines. Most magazines, whether they’re read by women or men, don’t publish investigative reporting or 10,000-word feature stories—they focus on things like fashion, travel, food, health and fitness. And when you do look at the magazines that publish long form, what you find is magazines like The New Yorker, whose readership is 50 percent women, or Vanity Fair, whose readership is 75 percent women. There are exceptions like Esquire and GQ, but the reason they publish long-form journalism has more to do with who the editors were and are than their being magazines whose primary audience is men. And you also have to remember that the long-form journalism is often complemented—in some ways, supported—by other kinds of content. What’s the first thing readers look at in The New Yorker? The cartoons. And Esquire deserves as much credit for its award-winning service journalism as for its feature stories. Sports has always lent itself to long-form, dating back to Ring Lardner’s You Know Me Al stories (you might even say The Iliad), and there’s a built-in male audience for it in the same way there’s a built-in female audience for fashion, but fashion is a story best told in pictures. in some ways, complaining about the gender split in the nominations is like saying the men who stayed on the Titanic get more attention than the women who made it into the lifeboats.

Okay, there’s truth in all that (though if magazine publishing has indeed hit an iceberg of changing business realities one could argue that it did so out of an “unsinkable” arrogance). More broadly, some of the byline gap, it should be noted, is likely due to structural problems that also hurt women in other careers. Some women take time off or dial back when they have kids, men not (yet) so much. Some steer themselves into softer and/or more “personal” forms of journalism. And yes, women who cover wars, sports, politics, tech or anything other than the “traditional” women’s beats still face sexism—from sources, from editors, from readers—and usually that sexism is subtle, and sometimes that sexism comes from women.

As many, including ourselves, have written, key to solving the byline gap is to get more women in editorial positions of authority. There are more women editing magazines that feature long-form, in-depth reporting and writing than when we became EICs six years ago. But not nearly enough.

And there is the issue of women’s magazines—which command an enormous number of readers; this list of the circulations of the 50 biggest magazines surprised even us—and are universally run (at least on the editorial side) by women. Here’s Ellie winner and Esquire/ESPN writer Chris Jones:

Hearing a lot about the struggles of women in narrative nonfiction. It would help if women’s magazines ran some, for starters.

— Chris Jones (@MySecondEmpire) March 7, 2012

Many of those titles started in a vastly different era for women. (Good Housekeeping, 1885!) God only knows the pressures related to advertisers—or of being a profit center in the very suddenly very sinkable world of print magazine conglomerates. None of the industry’s or society’s problem can be laid at their feet. And yet, and yet…if the problem of byline equity is in part a pipeline problem, then what women’s magazines publish, or don’t, affects the opportunities available to reporters and writers. Of both genders.