Of all the enemies American soldiers confronted during World War II, malaria proved to be among the most stubborn. The mosquito-borne disease was a constant scourge for GIs stationed in the Pacific and Mediterranean theaters. General MacArthur’s retreat to the malarial Philippine peninsula of Bataan in early 1942 led directly to his sickly army’s surrender to the Japanese a few months later. The illness continued to cripple American forces during the ensuing campaigns in Papua New Guinea and Guadalcanal, where it was so rampant that a division commander ordered that no Marine be excused from duty without a temperature of at least 103°F.

Troops in Southern Europe faced similar problems. During the Seventh Army’s Sicilian campaign from July to September 1943, 21,482 soldiers were admitted to the hospital for malaria; 17,535 were admitted for battle casualties. All in all, malaria accounted for almost a half-million hospital admissions and more than 300 American deaths during the war.

After some fits and starts, the military responded to the malaria outbreak with a full-out assault. The Army’s Medical Department dispatched malaria control units to war zones to clear and clean standing water and bombard malarial areas with recently developed insecticides like DDT and “bug bombs.” With access to quinine cut off by the Japanese conquest of Java, the government sped up trials of the anti-malarial medicine atabrine. Despite side effects such as turning the skin yellow, millions of tablets of the drug were distributed to troops toward the end of the war.

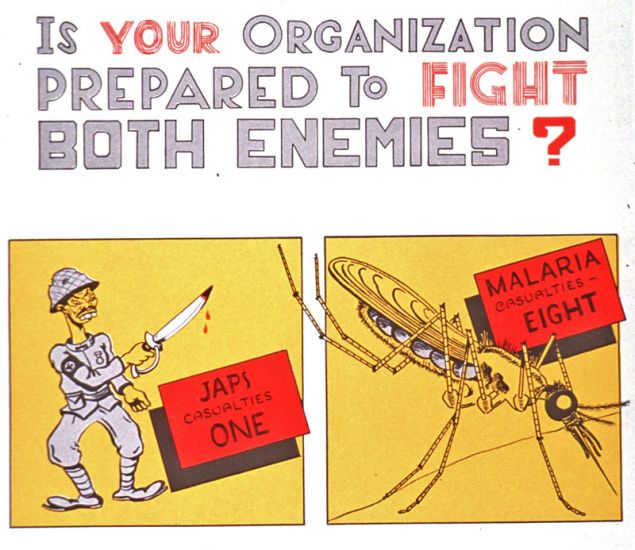

The military also warned soldiers about the dangers of the disease with an aggressive propaganda campaign that tried a variety of approaches, including patriotic appeals, racist caricatures, scare tactics, and goofy cartoons (including one drawn by the young Dr. Seuss). The campaign worked: Infection rates fell dramatically, and a healthier fighting force went on to claim victory in Europe and Asia.

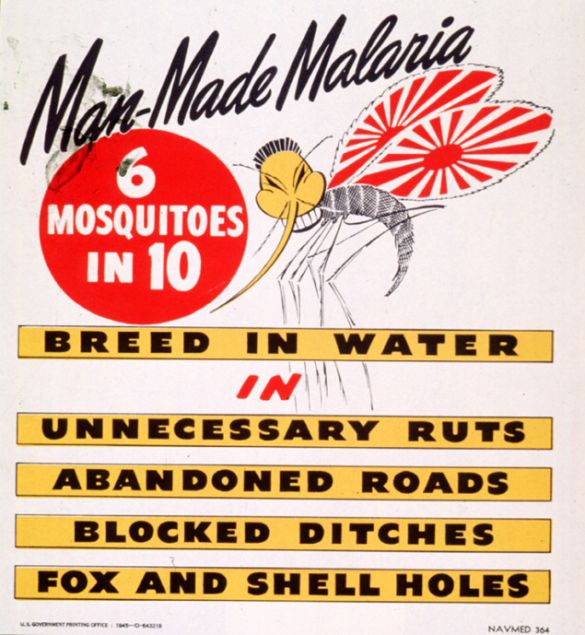

The military’s anti-malaria propaganda often relied on racist imagery to get its point across. This poster juxtaposes the “Japs” with apparently far more dangerous mosquitoes.

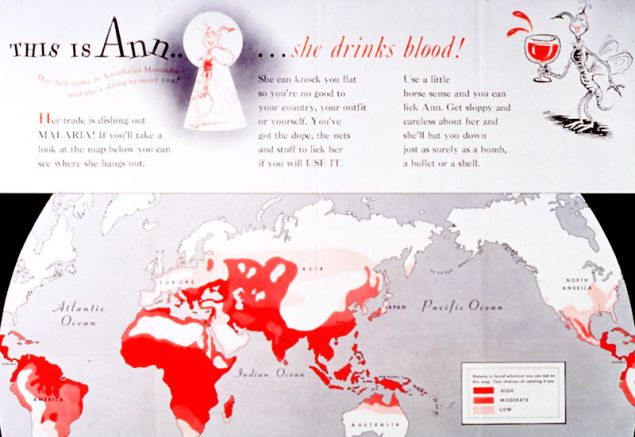

Theodor Geisel, aka Dr. Seuss, drew Ann, a whimsical blood-sucking mosquito, for a 1943 Army orientation booklet.

US National Library of Medicine

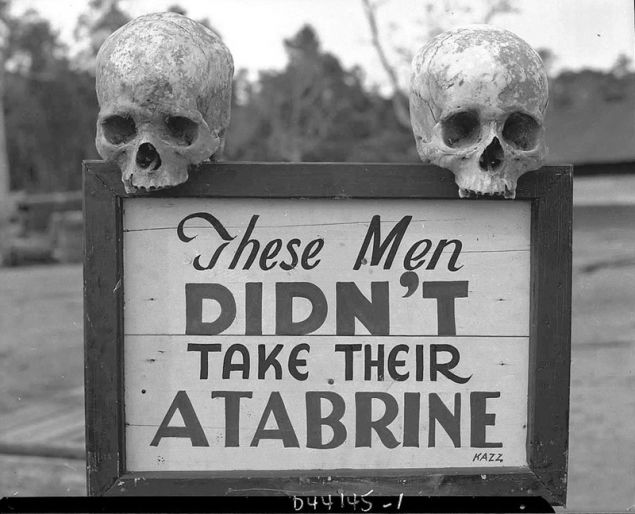

This sign at a field hospital in Papua New Guinea exaggerates the consequences of not taking anti-malaria meds. Despite its nasty side effects—like turning the skin yellow—atabrine was instrumental in getting a handle on the malaria problem.

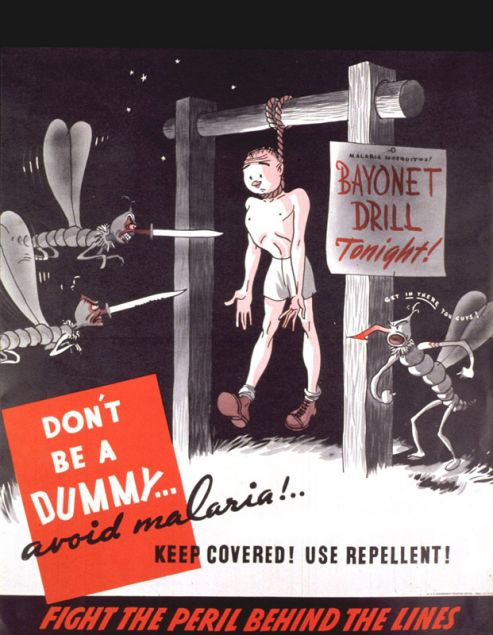

This poster prodded soldiers to keep their skin covered and use bug repellent.

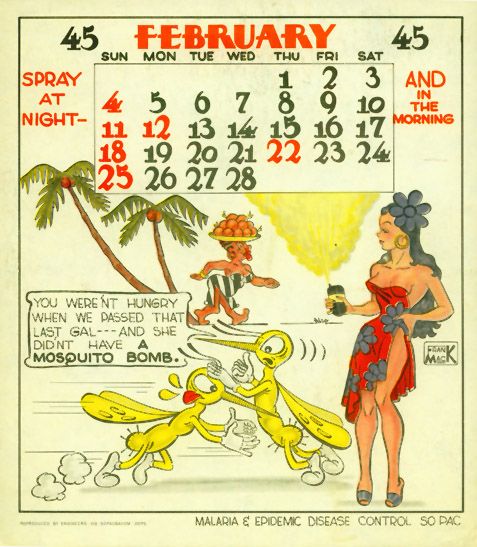

The cover-up rule clearly didn’t apply to pinup girls. Aerosol bug-spray dispensers known as “mosquito bombs” were developed in 1941 and proved extremely efficient mosquito-killers.

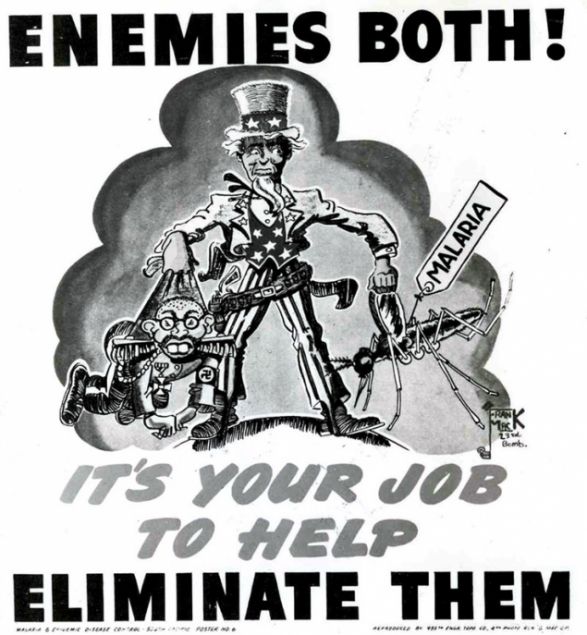

In this message from the military’s Malaria and Epidemic Disease Control unit, mosquitoes and Japanese Prime Minister Hideki Tojo are portrayed as pests to be exterminated.

Two officers inspect a nozzle used to spray DDT. The pesticide was tested by the Department of Agriculture in the early 1940s and reached combat theaters by 1944.

A slant-eyed mosquito menaces troops on a poster about how battlefields breed malaria.

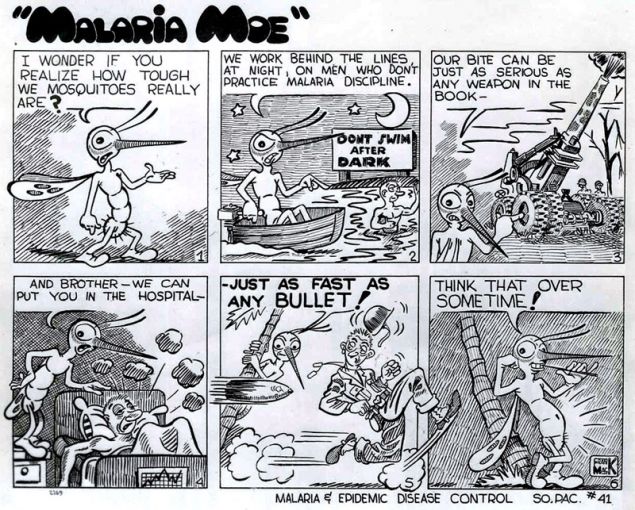

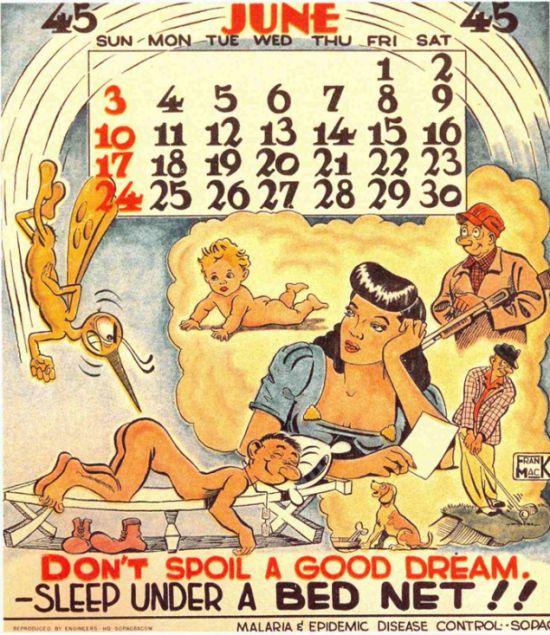

“Malaria Moe” ominously equates mosquitoes with enemy weapons. Cartoonist Frank Mack went on to work for Ripley’s Believe It Or Not after the war.

A GI sprays an Italian house with a mix of DDT and kerosene as a little girl looks on in horror.

The anti-malaria campaign wasn’t all drugs and DDT. Bed nets were an important—and effective—response to the mosquito menace.

Malaria control has come a long way since World War II. Today, the Air Force uses C-130 Hercules spraying systems to eradicate domestic mosquito populations.