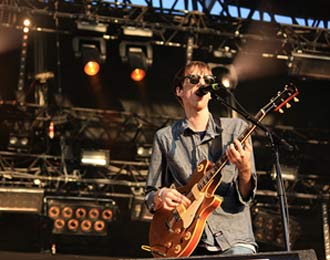

Kristin Dowling/PicturGroup

[Also read our interview with OK GO’s Tim Nordwind.]

Pop-rock quartet OK Go writes pretty catchy songs, but it’s their wildly creative YouTube endeavors that have made them famous. If you’re not already one of the 60 million YouTube viewers who’ve seen their “treadmill video”—the song is actually called “Here It Goes Again”—then go watch it before you read (below) how they made it work. Speaking of making things work, the band’s subsequent video blockbuster “This Too Shall Pass” involved a full-size Rube Goldberg contraption that filled an entire rented warehouse. (Why bother explaining? Go watch it below.) Their recent video, “White Knuckles” guest stars an entire pack of trained canines and their brand new one, “Last Leaf,” involves thousands of pieces of toast. OK Go’s videos, and its unique brand of fame, beg all sorts of fun questions—questions that singer/guitarist Damian Kulash was kind enough to answer for us. (We also hit up his always-stylish band mate, singer/bassist Tim Nordwind, to talk about the music that makes his video-addled mind tick.)

Mother Jones: Tell us about the taping of your treadmill video.

Damian Kulash: We made it with my sister, Trish Sie, who had recently retired from professional ballroom dancing, and we spent eight days at her dance studio in Orlando working on it. The first day or two, we tried out arrangements for the machines, trying to maximize the variety of moves that would be possible, and minimize the visual distraction of the machines themselves. After that, we played on the machines for four or five days, which is to say we hurled ourselves at them and saw what happened. Every so often we’d come up with a great move. Once we had a sufficient bag of tricks, we sequenced together a routine and began practicing. If I remember correctly, there were 17 or 18 takes, but we only completed the routine two or three times. Somewhat surprisingly, there were no injuries that required a hospital visit—the worst we got were scrapes and pretty serious rug-burn. Or I suppose you’d call it tread-burn.

The biggest challenge, choreographically, was figuring out how to keep something happening, how to keep something interesting in frame. Unlike normal dance moves, everything one does on treadmills ends by spitting you off-screen, so it took some work.

MJ: How long did it take to make your Rube Goldberg video?

DK: Just under six months. A team of a dozen engineers (now operating under the title Syyn Labs) responded enthusiastically to my posting and were willing to work within our nearly nonexistent budget. Within three months, we’d rented the warehouse and compiled a basic outline of how the machine would run. We’d mapped a basic arc of the song in broad, descriptive strokes like “small-scale, marble-based stuff here, large colorful flying things there” and anchored it to a few specific moments we knew we wanted to incorporate—like the kabuki screens, the sling-shot, and the paint cannons. A month later, the song had been broken up into six-second segments and each was assigned to an engineer or group of engineers to work on. Two or three weeks before the shoot date, the band returned from tour and basically moved into the work space.

Everyone’s view of what exactly makes a Rube Goldberg Machine magical is somewhat different, so these last few weeks were sort of a panicked rush to redesign and re-jigger parts of the machine around the band’s particular vision. Surprisingly, we mostly ran into problems where the modules were too well-designed, or were the product of much builder-ly skill or high-tech trickery. Engineers tend to want to solve problems unambiguously, with generous margins of error, but we wanted the machine to be flirting with impossibility. Things that are built to be reliable look that way, and the spirit of the machine needs to be hitting tiny, unlikely bulls-eyes rather than building bulls-eyes that you can’t miss. The last week was spent figuring out a camera path, lighting the machine, and manically testing and redesigning things—there were major changes up until the moment we started shooting, and tweaks all the way through the last take. My dad and my roommate had joined the team at this point. They and I designed the table of stuff that I’m sitting behind at the top of the first verse. I’ve never seen my dad stay up so late before—I remember him trying to perfect the arc of the mousetrap catapult at like 3 a.m. We shot for two straight days and did 89 takes. We only reached the end of the machine three times.

MJ: What inspires your inner videographer?

DK: Simple ideas. I’m particularly enamored of narrow creative boundaries—tight systems of rules that reveal human creativity pushing back. That’s the main reason I like shooting things in single takes. You have to rely on the idea itself to carry the full weight; you’re always watching the idea, not the filmmaking.

MJ: Does it bug you that OK Go is better known for its visuals than for the music

DK: People ask us that all the time, and it follows from the traditional logic of music videos. They’re supposed to be advertisements, funded by record labels to sell records. But our videos are our creative projects just like our songs, our albums, or our concerts are. We see them as endpoints, not ancillary promotional material. It sounds pat, but we get up in the morning because we love making things; we live for the thrill of chasing exciting projects.

MJ: Has all this YouTube love brought you any unusual offers?

DK: Sure. The day the treadmill video was released, we were playing a festival outside Moscow. Our label never promoted or even released our album there, but the success of the “A Million Ways” video led to an offer. We’ve headlined shows of thousands, occasionally tens of thousands, in other places where our label never promoted our record: Johannesburg, Taipei, Seoul, Oulu (that’s northern Finland—I’d never heard of it before). Our first gig in Brazil will be headlining the Brazilian MTV awards. We’ve also been contacted by lots of really fascinating and sometimes totally crazy people online. Mostly, it’s pretty inspiring—we tend to resonate with a brand of self-motivated creative people who connect with the independent, nontraditional spirit of the things we make, so we get really amazing emails from nun-chuckers and roboticists and inventors. We almost always invite further collaboration.

MJ: In a Washington Post op-ed this past August, you criticized Google and Verizon for hatching a plan that would undermine net neutrality, and called upon the FCC to push for regulatory action. What do you think the online world will be like in five to ten years if net neutrality isn’t preserved?

DK: I think it will essentially turn into cable TV. The big telecoms will decide what gets to travel in the fast lane, and instead of the free-for-all meritocracy we have now, we’ll get whatever they decide to serve us. The engine of innovation and new ideas that the internet has been for the last several decades will turn into a slightly sexier, pan-informational version of the on-demand service you get from your cable provider.

MJ: What chance do ordinary YouTube music fan have against the telecom behemoths?

DK: It’s the good old paradox of democracy. We are individually pretty small drops in the bucket, but collectively we are all powerful. The bad guys in the net neutrality fight have two basic tactics, and both of them can be defended against. The first is to offer wonderful new advances that they control. Everyone loves the idea of internet fast enough that HD movies download in seconds, but if only the telecoms or their partners get to use the high speeds, it’s not the internet: It’s glorified cable. So we just need to be careful not to fall for the bait. Faster is not better if it’s not still open, fair, and neutral. The second tactic is rhetorical: They’d like to convince us that the issue is too complicated and technical for us to understand—leave tech policy to tech companies, because it’s over our heads. It’s a classic. The bankers pulled off a similar feat, and look where that got us. So all we need to do here is keep reminding everyone that there’s nothing complicated about basic equality and fairness.