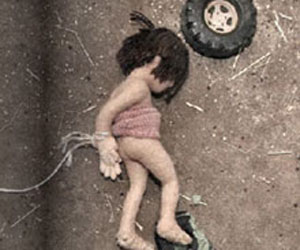

Image by Joe Sacco

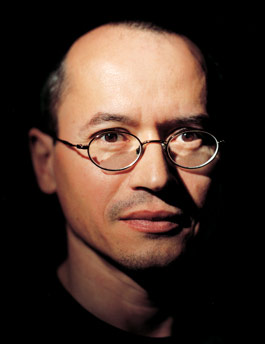

Amazon may call Joe Sacco a graphic novelist, but there’s nothing fictional about his work. With the sprawling Footnotes in Gaza (Henry Holt and Company) Sacco returns to Palestine, the place that first catapulted him into the international spotlight in 1993. His most ambitious project yet unearths a forgotten chapter in the 1954 Suez Crisis that left hundreds of Gazan civilians dead at the hands of the Israeli army. He spoke to us about changes in Palestine, his drawing habits, and what comics can do that photos and prose can’t from his home in Seattle while he was packing for a trip to Camden, New Jersey, on assignment for Harper’s.

Mother Jones: The first thing I noticed about this book is that it’s a doorstopper. Why is it so big?

Joe Sacco: The subject matter is big, and I wanted to try a book that sprawled a little. I wanted to give a lot of space to what I think deserved space. Especially if we’re talking about things that happened in the ’50s and controversial incidents, I wanted to allow for as much testimony as possible. Also, it’s about mass events—by that I mean there are a lot of figures in the frames, and to do that you need to draw; you can’t box it in.

MJ: How did you come to this specific story, and how did you decide to write a book on it?

JS: I went to Khan Yunis with Chris Hedges, and he actually wrote something up about what happened in Khan Yunis in 1956, and that was cut by Harper’s. And I thought, the people who are still around now, this might be the last chance to really talk to them, before they pass away and their recollections are completely lost. Of course their recollections are imperfect, but they’re all we have to go on as far as the record is concerned.

MJ: How much have things changed in that area of the world since you wrote Palestine?

JS: One is a surface difference: the camps. The refugee camps grew up quite a bit, so it was often difficult to tell the towns from the camps. But the major change was that the level of violence has gone up. When I was there [in the ’90s], people were throwing rocks and the Israelis were shooting, and it was pretty much contained within those parameters, rocks and bullets. Now, and when I was there, it had shifted from that to rocket-propelled grenades, mines, tanks, helicopter gunships, and fighter bombers. The plateau of what was acceptable violence had gone up greatly. When the Israelis first started using helicopter gunships in the occupied territories, it was shocking. But you sort of become used to it and that just becomes the new plateau. If you look at the level of violence against Gaza in the recent Israeli incursion of about a year ago, no one would have expected that 15 years ago, I think.

MJ: How long does it take you to construct a frame? Where do you start?

JS: At this point it’s become pretty intuitive. I seldom sketch out my ideas; I look at the page and in my head I can judge what captions belong where and where I should make a frame, or how I should divide a script up into frames. It’s something that happens in a matter of seconds. I can see what I want in my eyes before it’s on the page. I draw very quick outlines with my pencil to show where the frames are going to be and then I start drawing on the page. I draw my ideas directly onto the page—which leads to mistakes and a lot of erasing, but at a certain point, you reach a certain age, you’re not going to change your habits.

MJ: What do you think that pen and pencil and ink can tell that photographs and writing don’t manage to?

JS: I’m a big fan of photographs and a big fan of prose writing, too. But one of the advantages of comics is that you’re drawing frame after frame after frame, so almost in the background scenes you can create this atmosphere that’s following the reader around, that doesn’t necessarily relate to the foreground action but is somehow always present. For example, the way the buildings look—I can show that over and over again in the background, so in some ways I think you can really put the reader in that place, just with all these repeated images. If there’s mud in the background, you can show that in every frame, so the mud is following the reader around. If you’re a prose writer, really what you’re doing is just mentioning it once, you’re not going to keep mentioning it ever few lines—”and by the way, it was really muddy.” So it’s this constant reminder of what the place looks like.

MJ: What do you hope the reception of the book will be like?

JS: I want people to be able to look at this situation in a historical context and understand the layers of hard history that the Palestinians have endured, and get a sense of why perhaps there’s resentment in the region—it doesn’t come out of the blue. You might not want to excuse it, but it doesn’t come out of the blue. It bothered me personally that so much history gets lost. In some ways, I want this book to prompt an Israeli historian to really do a thorough research job from that end.

MJ: A lot of people struggle to define what you do or give it a name. What term do you like?

JS: I like “comic book.” The word “comic” might make some people cringe, but that’s the term I grew up with. I’d rather just stick with that than come up with a term that makes other people more comfortable or helps booksellers place the product somewhere on the shelf.