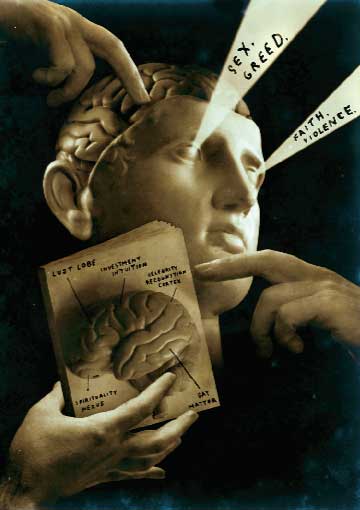

Illustration by: Jonathon Rosen

The Naked Brain: How the Emerging Neurosociety Is Changing How We Live, Work, and Love

By Richard Restak

Harmony Books. 272 pages. $23.

The Female Brain

By Louann Brizendine

Morgan Road Books. 279 pages. $24.95.

A Mind of Its Own: How Your Brain Distorts and Deceives

By Cordelia Fine

Norton. 243 pages. $24.95.

a recent article in Newsweek titled “This Is Your Brain on Alien Killer Pimps of Nazi Doom” reported on a study in which researchers scanned the brains of teenagers playing a violent video game and another group of teens playing a driving simulator. Kids who played the first-person shooter for 30 minutes “showed higher activity in the emotional centers of the brain, and less in the areas of concentration and inhibition” for an hour afterward. The study provided no direct link between badass games and badass behavior, but that didn’t stop the mother of one 14-year-old research subject from taking away his gaming console and encouraging him to play Monopoly instead. After all, there’s nothing wrong with a game that rewards you for ruthlessly driving your opponents into bankruptcy.

At least, not until neuroscientists tell us otherwise. Lately, brain science has been anointed the oracle we consult for the answers to life’s nagging questions. A Nexis search of major newspapers and magazines shows a 33 percent increase in brain-related articles in the past 10 years, with pop neuroscience chiming in on issues that were once the realm of behaviorism, psychology, religion, and even marketing. Scientists are looking inside the brain for clues to why people prefer Coke to Pepsi and how the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex reacts to Super Bowl ads. Having isolated the part of the brain that “predicts” what shoppers will buy, a Stanford researcher intoned, “It’s likely that these mechanisms are there for reasons related perhaps to survival.” The brain now shows up in articles in O magazine on dieting and in items about “earworms”—those songs that stick in your head—as well as in serious-sounding books about how religion is rooted in our “God gene” and how having kids makes women’s brains smarter. The brain even does self-help. A series of “neurobics” books promises to keep your mind healthy using “exercises based on the latest scientific research from leading neurobiology labs,” and a title coming out this fall promises to show “how the new science of neuroeconomics can help make you rich.”

It’s comforting to think that our brains hold the key to everything from stock tips to teenage violence, but much of this feels like the 21st-century version of phrenology, with brain scans replacing skull palpation. Should research done on college kids looking for easy beer money influence what we think about motherhood, free will, or God? Considering how isolated and confounding the brain is, not to mention how young the field of neuroscience is, should we even look for answers there?

Brain science is an odd place to search for certainty, in part because it reveals just how mysterious the machinery of consciousness really is. In January, the New York Times blamed the brain for the futility of keeping New Year’s resolutions, quoting a scientist who said that people are just “meat machines” who only think they’re in control. A few days later, the Times wrote about the New Yorker who leapt in front of a subway train to rescue a man who’d fallen onto the tracks, speculating that special altruism-boosting “mirror neurons” made him save the day. In The Naked Brain, neurologist and neuropsychiatrist Richard Restak offers up page after page of these kinds of tales of the brain’s unnerving secret agenda. Subjects in one study he cites were flashed words like “impolite” and “considerate,” then put into scenarios in which they acted out the words that had “primed” their behavior. In another study, white subjects were put inside a functional magnetic resonance imager (fmri) and subliminally shown a black face, causing the amygdala—the brain’s threat detector—to light up in a pixelated shout of “Racist!”

Restak presents these examples to support his predictions about what he calls the “neurosociety,” a near-future place where advances in neuroscience will jump “from the laboratory to the boardroom, the showroom and the bedroom,” enabling politicians, lawyers, and advertisers to exploit our brains’ vulnerabilities. Fortunately, Restak is too much of a skeptic to fully raise the alarm over what might sound like mind control. Unlike the Newsweek piece, which offered brain scans as hard proof, Restak makes plenty of disclaimers about what neuroscience can and can’t tell us. Even the “racist brain” softens when put into context. Those initially damning fmri images also show that the frontal lobes, which handle higher functions such as decision making, eventually overrule the amygdala. Before you draw a conclusion about that brain, give it a moment to think.

The abundance and malleability of brain research make it an extraordinarily tempting explanatory tool, especially if you have something to prove. Louann Brizendine’s The Female Brain sets out to dispel the belief, popular throughout most of the 20th century, that neurologically speaking, “women were essentially small men.” Unfortunately, rather than conducting a cautious inquiry into what makes the female brain uniquely female, she tries to show that women’s brains are superior to men’s. The result reads like a “Cathy” cartoon with neurons. Estrogen is “the queen,” while oxytocin, the neurohormone associated with attachment and parenting, is a “fluffy, purring kitty.” And there are groaners such as this one: “Maneuvering like an F-15, Sarah’s female brain is a high-performance emotion machine—geared to tracking, moment by moment, the non-verbal signals of the innermost feelings of others.” Ack!

In her enthusiasm, Brizendine gets sloppy. To support the claim that women are inherently better communicators, she cites a made-up statistic that women use 20,000 words a day while men use 7,000. But her biggest sin is peddling the misconception that if something is linked to the brain, it’s somehow more true. Take this sentence about how tough it is for women to choose between work and family: “We know that the female brain responds to this conflict with increased stress, increased anxiety, and reduced brainpower for the mother’s work and her children.” What happens to its meaning if you take away the word “brain”?

The science of the human brain may be one of the rare instances in which knowledge isn’t power. Brizendine wants to unlock its secrets to liberate women, but what good is it to know which neurotransmitter is the source of your troubles if you can’t—short of taking drugs—regulate it? Furthermore, brain scans can only tell us about a moment in time, while the brain is responsible for everything you do, all the time, without end. Which is why Restak is right to wonder which tells you more about someone: an fmri or the daily continuity of his words and actions?

Maybe we shouldn’t be looking to our brains for answers but for confusion, as Cordelia Fine does in A Mind of Its Own. Rather than wow us with brain enigmas, or use the brain to settle a score, she introduces us to the brain’s entertaining, all-too-human forms—”The Vain Brain,” “The Immoral Brain,” and “The Deluded Brain.” Fine, a psychologist, calls out the brain for what it is—a stubborn, unreliable piece of junk. The brain constantly feigns knowledge, she writes. “But things don’t stop there. The brain also lays claim to knowledge of what it cannot know. So omniscient does the pig-headed brain think itself that it even affects to be acquainted with knowledge that doesn’t exist.” Consider the study in which college students were asked to invent facts, such as the name of the only woman to sign the Declaration of Independence. Asked to recite their invented facts, the students eventually became convinced they were telling the truth. The brain is not to be trusted, and as a result, you are not to be trusted.

If we must rely on our untrustworthy brains to better understand our brains, can we ever hope to know what’s really going on up there? Maybe not. As one neuroscientist told me, “We may already know everything we’re going to know about the brain, and from this point forward we’re chasing our tails.” In the end, the brain may be God’s cruelest joke, enticing some of the smartest people in the world to twist away at a Rubik’s Cube that has no solution. If brain science is good for anything, it’s a humbling reminder that we don’t know shit about ourselves. I suspect the mom in the Newsweek article started out not liking her son’s video games. His brain scan gave her an excuse to pull the plug, but her brain had already made up its mind. That kid should get his Xbox back.