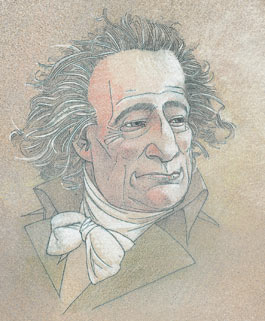

Illustration: David Johnson

The Trouble with Tom: The Strange Afterlife and Times of Thomas Paine By Paul Collins. Bloomsbury. 288 pages. $24.95

Thomas Paine and the Promise of America By Harvey J. Kaye. Hill and Wang. 326 pages. $25.

Tom Paine is the original American—and the original un-American. That’s why there’s no national monument dedicated to this Founding Father. And that’s why, if Congress ever gets behind one, it ought to place a large statue of him on the grounds of Mount Rushmore, his arm raised as if throwing a stone. The position should be ambiguous, and suggestive, as though he might be a soldier for those faces carved out of the mountain, or might be coming at them. Approaching the image, one should see that in his raised hand is no stone at all, but a quill pen.

A hero of the American Revolution who was shunned in his later years and reviled after his death, Paine has lurked in the shadows of history for generations. Recently his memory has come again into the light, attracting Americans of all ideological stripes. To the opposition left, he’s an icon of defiant, unorthodox idealism. To the ruling right, he’s a philosopher of American exceptionalism and our national burden to spread democracy worldwide. Both sides have a valid claim, yet neither captures his full breadth.

Paine landed in Philadelphia on November 30, 1774. The 37-year-old Englishman had a nose for trouble, and he moved, unerringly, toward it. Not five months after his ship landed, clashes at Lexington and Concord left 95 American casualties. “When the country,” Paine wrote later, “into which I had just set foot, was set on fire about my ears, it was time to stir. It was time for every man to stir.” That fall, Paine set out to write a manifesto on the meaning of the conflict between Britain and her once-loyal subjects in the New World. First printed in Philadelphia on January 10, 1776, Common Sense ignited a wildfire.

The numbers were astonishing—150,000 copies were in print within a few months (roughly equivalent to 15 million copies today). But its real impact can best be measured in the way that colonists from Massachusetts to South Carolina moved in the direction that Paine prescribed. “Without the pen of Paine,” as one contemporary wrote, “the sword of Washington would have been wielded in vain.”

Today, Paine’s words still resonate in thundering tones. Their leading point—that the Colonies should unite to throw off the rule of the king—we now take for granted, because it came to pass. But another theme of Common Sense leaps out at us today because it is the object of so much contention. With a mystical fervor, Paine argued that the new nation possessed an inherent virtue that would spark a fire to burn the old order down. “The cause of America,” he wrote, “is in a great measure the cause of all mankind…. We have it in our power to begin the world over again.”

If you hear echoes of “regime change,” there’s a good reason: Paine not only advocated the idea but risked his life for it. After the surprising success of the American Revolution, he visited his native England, where he wrote The Rights of Man, a brief against the power of kings and a celebration of radical change. Drummed out of England, Paine escaped to revolutionary France—out of the frying pan and into the fire. Sentenced to death by Robespierre, he escaped his fate only by a miraculous accident (the executioners marked his cell door on the wrong side). Free again, Paine lashed out at President Washington, whom he blamed for not coming to his rescue. This alone would have been enough to secure his lasting ignominy in America, but Paine had more in mind.

In 1795, he released the final, and most daring, chapter of his classic trilogy. The Age of Reason, an attack on traditional religion and the Christian church, made him one of history’s great apostates. Scurrilous attacks—that he was a hopeless drunk, that he beat his wife, that he raped a cat!—followed him in his waning years. It was symbolically appropriate that, as he tottered around New York City, he could find no place to be buried. (Even the archliberal Quakers spurned his request.) When he died in 1809, six people attended his funeral in New Rochelle, New York, and his tombstone was desecrated soon afterward.

Paine’s legacy—his physical remains as well as his ideological heritage—is the subject of two recent books. Paul Collins’ The Trouble With Tom is an idiosyncratic study of what happened to Paine’s bones. The strange story begins with one of Paine’s fiercest critics, who had a change of heart and, in a high-minded grave robbery, dug up the old radical’s remains and brought them to England, where he hoped they’d have the same kind of power that Paine’s living words had. But the result was nothing so clear. Indeed, The Trouble With Tom, which seems to begin as a quest to find the remains—a metaphor for understanding Paine—becomes a meditation on how elusive both are. The book is full of wry musings and incisive observations about history; still, Collins’ cerebral wanderings can obscure the physical journey that may be, for some readers, the reason to go along in the first place—that is, how the travels of Paine’s remains became, as Collins says, “those of democracy itself.”

Where this tale leaves off, Harvey J. Kaye picks up, in Thomas Paine and the Promise of America. Kaye identifies Paine as a “radical democrat” and dubs him the father of two centuries of leftists, from Elizabeth Cady Stanton to Franklin D. Roosevelt and C. Wright Mills. “Paine,” Kaye writes, “had turned Americans into radicals—and we have remained radicals at heart ever since.” As Kaye sees it, Paine laid an ideological foundation for such modern liberal bulwarks as education grants and pensions for the elderly, not to mention railing against the abuses of “the propertied, powerful, and pious.”

But the left is hardly alone in claiming Paine. He is also a neoconservative hero for his assault against the tyranny of established governments and his call to spread democracy—if necessary, at gunpoint. After many decades as an official anathema—Theodore Roosevelt dismissed him as a “filthy little atheist”—Paine has had a resurgence recently, in no small part because figures like Ronald Reagan embraced him, entranced by his narrative of America’s special destiny.

Yet trying to enlist Paine as a modern-day liberal or conservative is like trying to catch a great river in a tin pail: We’ll surely fail, and we’ll miss the point if we try. The themes of his life clearly resonate today, not because he can be neatly summed up, but because he provoked basic debates that still define our national life: How should the American experiment in democracy evolve, and how should it apply abroad? Which rights are natural to all people, and which can be assigned or revoked by the state? What role should institutional religion play in national life?

Perhaps no subject of Paine’s is more relevant than that last one, and perhaps none is more discouraging for the left. Paine’s triumph came when he cast America as the cradle of freedom and the executioner of tyranny. He fell from favor when he denounced the country as fallen and fearlessly took on the great, quiet power of American life: organized religion. This helps explain why both sides in today’s debate may claim Paine, and why one evokes the swaggering hero of ’76 and the other the disheveled old revolutionary who couldn’t find a place to rest his weary bones.