Here’s the coronavirus death toll through August 7. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

Here’s the coronavirus death toll through August 7. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

A couple of people have asked for an update of a chart I put up a few weeks ago comparing the COVID-19 case rate with the death rate. Here it is:

During the first round of COVID-19, the death rate started to decline about two weeks after the case rate began falling. If the same thing happens this time around, deaths have already peaked and will start to decline in about a week or so.

I’m not saying this is what will happen. There have been too many surprises already in the COVID-19 numbers, and the actual death rate will depend a lot on how seriously everyone is taking the recommended countermeasures (masks, social distancing, etc.). I can’t predict that—and neither can anyone else—which means I can’t predict the death rate trend either.

Still, if the second round of COVID-19 is like the first round, late July would have been a decent baseline guess for peak deaths—which turned out to be the case—and mid-August is our best guess for the start of the decline.

My mother has five cats: Tillamook, Luna, and the three stripeys. Luna is shy around strangers, but my sister and I have been around enough over the past few weeks that she’s finally gotten used to us. Luring her with plates of food helped too. In any case, she now hangs around inside the house sometimes, and she has decided that Tillamook is her favorite uncle. She just loves curling up with him, and Tilly doesn’t mind either.

Today brings a new study of COVID-19 with some interesting results. The basic question is whether big, dense cities are more vulnerable to outbreaks than smaller towns and rural areas. The authors come to two conclusions:

So the worst possible place to live is a big city with low density. These are mostly found out west: Houston, Phoenix, San Antonio, San Diego, etc. The best place to live would be a relatively small city with high density: San Francisco, Boston, Washington DC, and so forth.

I’m not sure how much this matters since most of us can’t move, but at least it gives you some idea of how dangerous your current residence is.

So how did we do on the jobs front in July? Obviously we’re in new territory these days, but I think the answer is “meh”:

The BLS reports that we gained 1.8 million jobs, which is less than half what we gained in June. On the unemployment front, there were 6.3 million fewer workers who had been unemployed for 5-14 weeks, but 4.6 million more workers who had been unemployed for 15-26 weeks. The industries with the biggest gains were leisure, temp services, and retail.

On the earnings front, the news was all bad: hourly wages of blue-collar workers were down about 5 percent on an annualized basis. Wages for retail workers were down 3.4 percent from June, or 42 percent on an annualized basis. That’s not a typo. It would appear that retailers took the opportunity of COVID-19 to slash pay for their workers. Isn’t that lovely?

Here’s the coronavirus death toll through August 6. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

This is probably a Canadian aluminum worker snickering under his breath because he's put one over on Donald Trump. But today marks an end to that.Image Source/Cultura/ZUMAPRESS

It’s been just over a month since President Trump signed a new trade agreement with Canada and Mexico, so guess what he did today? He turned right around and placed new tariffs on Canadian aluminum:

The White House said certain types of aluminum were surging into the U.S., depressing the U.S. industry. The administration justified the tariffs, which will be set at 10%, using a national security provision and argued that a depressed U.S. aluminum industry threatens U.S. national security.

“Earlier today I signed a proclamation that defends American industry by reimposing aluminum tariffs on Canada,” President Trump said during a speech at a Whirlpool factory in Clyde, Ohio. “Canada was taking advantage of us, as usual,” he said. “The aluminum business was being decimated by Canada, very unfair to our jobs and our great aluminum workers.”

I don’t know about “certain types” of aluminum, but it’s pretty easy to dig up total US imports of aluminum from Canada:

Maybe I’m missing something, but it doesn’t look like there’s been a surge in aluminum imports from Canada. Maybe there is if you do it by tonnes instead of dollars? Or if you look only at certain specialized types of aluminum products? Or something.

More likely, Trump still hasn’t gotten over being humiliated by Justin Trudeau at that G7 meeting a few years ago. That’s more his style.

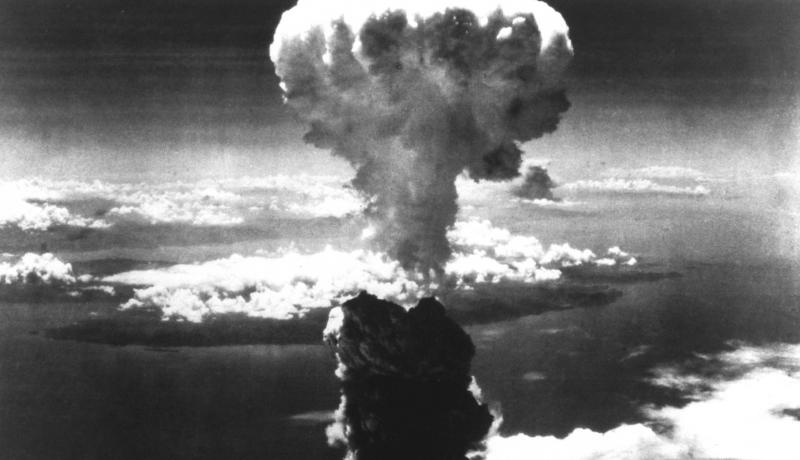

A few years ago I wrote a post about new research into the cause of Japanese surrender in World War II. Today is the 75th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing, and I thought it might be interesting to repost it. Here it is.

There has long been a scholarly debate about whether it was necessary for the United States to use atomic weapons to bring World War II to an end. Traditionalists say yes: If not for Fat Man and Little Boy, Japan would have fought to the last man. But revisionists argue that by August of 1945: (a) Japan’s situation was catastrophically hopeless; (b) they knew it and were ready to surrender; and (c) thanks to decoded Japanese diplomatic messages, Harry Truman and other American leaders knew they were ready. A Japanese surrender could have been negotiated in fairly short order with or without the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

For various reasons I’ve always found the revisionist view unsatisfactory. After all, even after the Hiroshima bomb was dropped, we know there was still considerable debate within the Japanese war cabinet over their next step. Surely if Japan had already been close to unconditional surrender in early August—and for better or worse, unconditional surrender was an American requirement—the atomic demonstration of August 6 would have been more than enough to tip them over the edge. But it didn’t. It was only after the second bomb was dropped that Japan ultimately agreed to surrender.

But although the revisionist view has never persuaded me, a new revisionist view has been swirling around the academic community for several years—and this one seems much more interesting. Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, a trilingual English/Russian/Japanese historian, reminds us that the actual timeline of Japanese surrender went like this:

August 6: Hiroshima bomb dropped.

August 8: Soviet Union declares war on Japan and invades Manchuria.

August 9: Nagasaki bomb dropped.

August 10: Emperor Hirohito breaks the cabinet deadlock and decides that Japan must surrender.

So what really caused the Japanese to finally give up? Was it America’s atomic bombs, or was it the Soviet Union’s entrance into the Pacific war? Hasegawa, based on meticulous research into primary sources, argues that it was probably the latter—though not quite in the way we usually think. Gareth Cook summarizes Hasegawa’s argument in the Boston Globe:

According to his close examination of the evidence, Japan was not poised to surrender before Hiroshima, as the revisionists argued, nor was it ready to give in immediately after the atomic bomb, as traditionalists have always seen it.…Americans, then and today, have tended to assume that Japan’s leaders were simply blinded by their own fanaticism, forcing a catastrophic showdown for no reason other than their refusal to acknowledge defeat.…But Hasegawa and other historians have shown that Japan’s leaders were in fact quite savvy, well aware of their difficult position, and holding out for strategic reasons.

Their concern was not so much whether to end the conflict, but how to end it while holding onto territory, avoiding war crimes trials, and preserving the imperial system. The Japanese could still inflict heavy casualties on any invader, and they hoped to convince the Soviet Union, still neutral in the Asian theater, to mediate a settlement with the Americans. Stalin, they calculated, might negotiate more favorable terms in exchange for territory in Asia. It was a long shot, but it made strategic sense.

On Aug. 6, the American bomber Enola Gay dropped its payload on Hiroshima.…As Hasegawa writes in his book “Racing the Enemy,” the Japanese leadership reacted with concern, but not panic.…Very late the next night, however, something happened that did change the plan. The Soviet Union declared war and launched a broad surprise attack on Japanese forces in Manchuria. In that instant, Japan’s strategy was ruined. Stalin would not be extracting concessions from the Americans. And the approaching Red Army brought new concerns: The military position was more dire, and it was hard to imagine occupying communists allowing Japan’s traditional imperial system to continue. Better to surrender to Washington than to Moscow.

In some sense, the real answer here is probably unknowable. Two events happened at nearly the same time, and they were closely followed by a third. Figuring out conclusively what caused what may simply not be possible. Probably they both played a role. Still, aside from the documentary evidence that Hasegawa amasses, his theory accounts for other aspects of the war. Like the dog that didn’t bark in the night, Japan didn’t give up after the fire bombing of Tokyo. Nor did Germany surrender after the fire bombing of Dresden. And although it’s undeniably true that atomic bombs are a more dramatic way of destroying a city than conventional weaponry, it’s also undeniably true that simply destroying a city was never enough to produce a surrender. So why would destroying a city with an atomic bomb be that much different?

This is fascinating stuff. At the same time, I think that Cook takes a step too far when he suggests that Hasegawa’s research, if true, should fundamentally change our view of atomic weapons. “If the atomic bomb alone could not compel the Japanese to submit,” he writes, “then perhaps the nuclear deterrent is not as strong as it seems.” But that hardly follows. America in 1945 had an air force capable of leveling cities with conventional weaponry. We still do—though barely—but no other country in the world comes close. With an atomic bomb and a delivery vehicle, North Korea can threaten to destroy Seoul. Without it, they can’t. And larger atomic states, like the US, India, Pakistan, and Russia, have the capacity to do more than just level a city or two. They can level entire countries.

So, no: Hasegawa’s research is fascinating for what it tells us about a key event in history. But should it change our view of atomic weaponry or atomic deterrence? I doubt it. It’s not 1945 anymore.

I’ve been sick all day with some kind of stomach bug. However, I should be fine by tomorrow, so join me here for the exciting July jobs report!

This is the San Diego Freeway near Culver Drive in Irvine. Needless to say, it’s a long exposure taken at night.