Here’s the coronavirus death toll through December 15. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

Here’s the coronavirus death toll through December 15. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

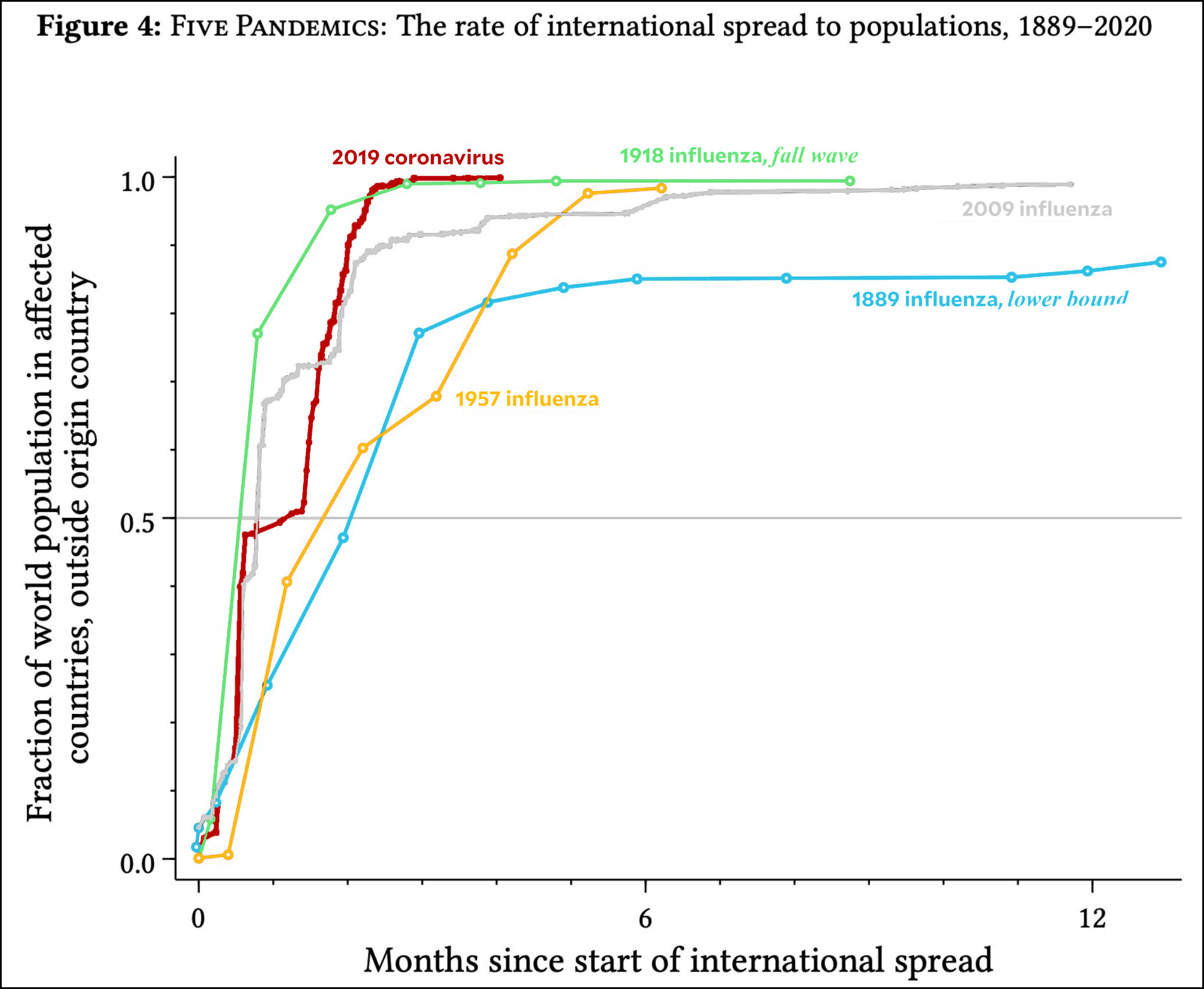

How fast did the COVID-19 pandemic spread around the world? What with planes, trains, and automobiles now commonplace, you’d think it would be pretty quick compared to past pandemics. But Michael Clemens and Thomas Ginn decided to check this out, and they found little difference over the centuries:

The 1918 influenza epidemic spread faster than the 2019 coronavirus epidemic. The 1889 and 1957 influenza epidemics were a little slower, but not by much:

If spread depends heavily on the modern ‘age of mobility’, the spread of recent pandemics should be supercharged relative to older pandemics with similarly infectious pathogens. But there’s nothing like that in the data. Across the four past pandemics we study, from 1889 to 2009, the time it took for the pathogen to reach the median person on earth only varied by *six weeks*.

….We separately show, for each of the four past pandemics, that the time-of-arrival has no negative relationship with mortality. Staving it off a bit longer did not save lives. Action behind the border did; inaction did not.

This doesn’t actually surprise me that much. Mobility may have been lower in the past, but it doesn’t take a lot of people to spread a pathogen. One or two will do quite nicely. To spread from, say, Europe to the US in 1889, you just have to wait for that one person to sail across the Atlantic. This adds a week or two compared to traveling via United Airlines, and then another week or two because the probability of that one guy sailing over is lower than it is today. But once he’s here, it’s all over.

The authors stress that emergency restrictions on international travel during a pandemic aren’t completely useless. It’s just that their effect is small: halving a country’s exposure to international mobility produces a delay in pandemic arrival on the order of only one week. Most of the benefit of social distancing (and travel restrictions are just a form of social distancing) comes from reducing personal interactions inside national borders.

Kevin Drum

If the opportunity arises, should you accept an invitation to appear on a podcast or talk show? If it’s a progressive show, then sure. But what if it’s something else? Here’s my advice, by way of a brief taxonomy:

Long-running conservative shows. Examples include Sean Hannity, Hugh Hewitt, and so forth. Just don’t do it. There are two reasons to skip these shows. First, unless you’re a real pro, the host will rip you to shreds. Don’t make the mistake of thinking they’re morons: they’ve been doing this a long time and they know precisely how to frame the conversation in the worst possible way for you. And it’s their show! They can control what direction it takes. What’s more, their audience is mostly confirmed conservatives. You’re pretty unlikely to change any minds.

Non political shows. These are the best, as long as you properly gauge your audience. The hosts are likely to be fairly neutral and the listeners are people who probably aren’t especially political and are therefore especially persuadable. The key is to keep it simple. No matter how little you think nonpolitical types know, they probably know even less.

Semi-political shows. I suppose Joe Rogan is the best known example of this. I’d say that your decision about whether to appear should depend on what the topic is. If it’s a tricky one that you don’t know a lot about, it might be best to skip it. Even with a non-hostile host, you could end up going down in flames just via “common sense” questioning that forces you to sound too much like an ivory tower academic. But if it’s something you know pretty well? Then sure. You have a good chance to have a nice conversation and a good chance to persuade the audience, which is likely to be fairly mixed.

Centrist shows. These are run by hosts who have a reputation for being tough on all comers, which makes it difficult to say if you should appear. On the one hand, you might not enjoy having to spend most of your time defending the most borderline aspects of your case. On the other hand, the audience for these shows is likely to be pretty good pickings: people who respond to evidence and good arguments and pride themselves on not being partisan hacks. In any case, if you do appear on a show like this then for God’s sake be sure to study up on the most vulnerable parts of your argument. This is no time for epistemic closure.

No matter what type of show you appear on, the oldest advice is still the best: know your audience. Don’t be lazy! If you know you’re going to be talking to a conservative audience, you need to summon up arguments that might appeal to a conservative. Ditto for young, old, male, female, Black, white, and so forth. If Vogue wants you to appear on a podcast because some kind of fashion controversy is in the news, at least think a bit about what a Vogue audience might respond to. Don’t make jokes about how you’re a slob. You may think they’re funny but your audience probably won’t. Even if you have to fib a little bit, it won’t kill you to read at least a Wikipedia entry or two and pretend that you think fashion is an important topic that’s too often mocked in popular discourse.

This picture of a surfer was taken from the Huntington Beach pier. The waves were breaking nicely at about 3 feet toward the end of the day, which attracted lots of novice surfers and only a few pretty good ones, like this guy.

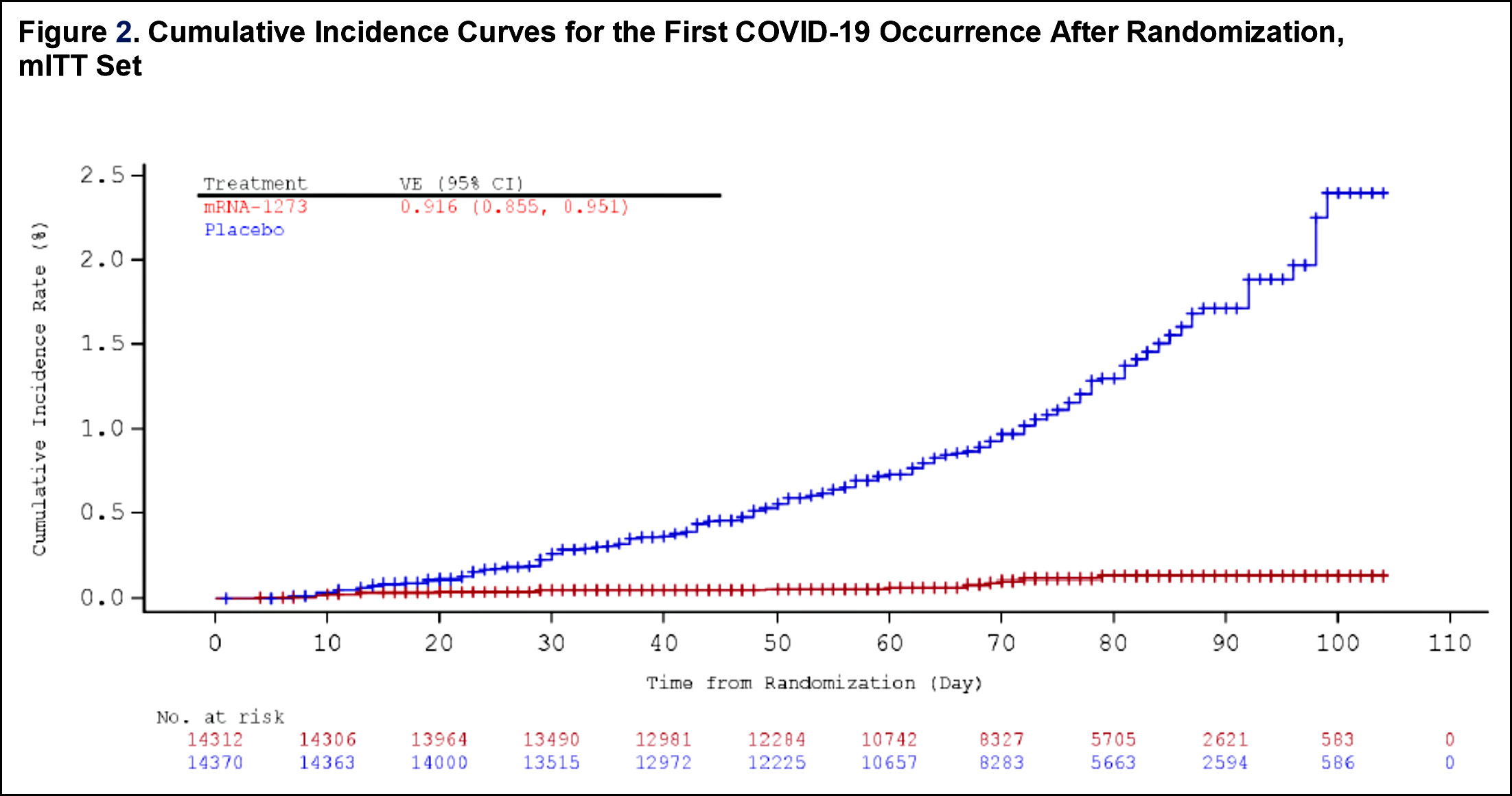

The FDA has released its briefing document for Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine, and it looks pretty great:

This looks even better than the Pfizer vaccine, and it has the added advantage of requiring only normal refrigeration for storage, rather than the super-cold refrigeration required by Pfizer’s product. As with the Pfizer vaccine, patients reported a fairly normal incidence of minor side-effects, including headache, fever, fatigue, muscle aches, joint pain, chills, and pain at the injection site. There were apparently no serious side effects. The Moderna product is a two-shot vaccine, with the second shot given 28 days after the first—although the chart suggests that it’s pretty effective even after the first dose. Like the Pfizer vaccine, it appears to become effective about ten days after the first injection.

One other thing of note. This might be simply a coincidence, but every single person in the vaccine group who contracted COVID-19 (five in all, compared to 90 in the control group) were white people under the age of 65. No person of color contracted COVID-19, and neither did anyone over the age of 65.

The FDA’s vaccine advisory committee meets on Thursday to discuss the results of the Moderna testing. They seem very likely to recommend an emergency use authorization, and the FDA will probably issue one on Friday. By next week we should have two highly effective vaccines in active use.

Here’s the coronavirus death toll through December 14. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

This is a colorful row of mannequins outside a clothing shop just off Slauson Blvd. near the Harbor Freeway.

Imago via ZUMA

For some reason this doesn’t seem to be common knowledge, so it’s worth mentioning that the FDA’s vaccine advisory committee will be meeting again this Thursday to discuss emergency approval of a COVID-19 vaccine. This time it’s the Moderna vaccine, and there’s every reason to think they will recommend approval and the FDA will grant it. The United States purchased 100 million doses last summer and another 100 million doses a few days ago. Since the Moderna vaccine requires two shots, this is enough for 100 million people.

Between the Pfizer vaccine and the Moderna vaccine we will have enough to innoculate 150 million people, which will probably take us through mid-2021 at the rate we can reasonably expect the vaccines to be distributed.

This is good news, and there’s more: the Moderna vaccine appears to be slightly more effective than the Pfizer vaccine, and it can be stored in ordinary refrigerators for up to a month. This should make distribution much easier in more places than the Pfizer vaccine.

Between these two vaccines, as well as others coming down the pike, the US should be well supplied with enough vaccine to provide an innoculation to everyone who wants one over the next year or so. Ditto for other countries. It’s the beginning of the end.

Rod Lamkey - Cnp/CNP via ZUMA

The two biggest impediments to passing a COVID relief bill are money for local governments (opposed by Republicans) and liability protections for businesses (opposed by Democrats). So maybe the folks who designed the bipartisan $908 billion rescue package should just ditch both of them for now?

In a desperate bid to reach agreement, that group of lawmakers decided over the weekend to split their proposal into two pieces — carving out the most contentious items, money for local governments and liability protections for businesses, into a separate bill. The other bill, with a $748 billion price tag, would include broadly bipartisan funding for schools and health care.

This is hardly an ideal solution, but it would get unemployment relief to those who have been furloughed because of the pandemic. Apparently the plan now is to try and get the $748 billion package appended to the omnibus spending bill, which has to be passed within the next week. Here’s hoping.

I have pretty rigorously avoided writing about the “legal” challenges to Joe Biden’s election victory, since we all know that none of them are meant as serious legal arguments. They are merely tokens from the Republican Party leadership to its base that, by God, they are going to fight to the end.

But with the Electoral College now voting, I’ll break my routine and comment on this:

I don’t get the “But Democrats questioned the legitimacy of the election in 2016!” stuff. If you condemned that at the time, doing the same thing — but much worse — is not exactly an ethically or logically serious response.

— Jonah Goldberg (@JonahDispatch) December 14, 2020

Goldberg is right, of course, but in the least of the ways that this is ridiculous. The primary way this is ridiculous is that there’s a huge difference between:

and

To pretend that these two things are even comparable, let alone the same, is nuts. If Fox News wants to blather on about it, that’s fine. There’s nothing we can do about that. But surely no one else should join in on this nonsense.