Walter Scott’s death in South Carolina, at the hands of now-fired North Charleston police officer Michael Slager, is one of several instances from the past year when a black man was killed after being pulled over while driving. No one knows exactly how often traffic stops turn deadly, but studies in Arizona, Missouri, Texas, Washington have consistently shown that cops stop and search black drivers at a higher rate than white drivers. Last week, a team of researchers in North Carolina found that traffic stops in Charlotte, the state’s largest city, showed a similar racial disparity—and that the gap has been widening over time.

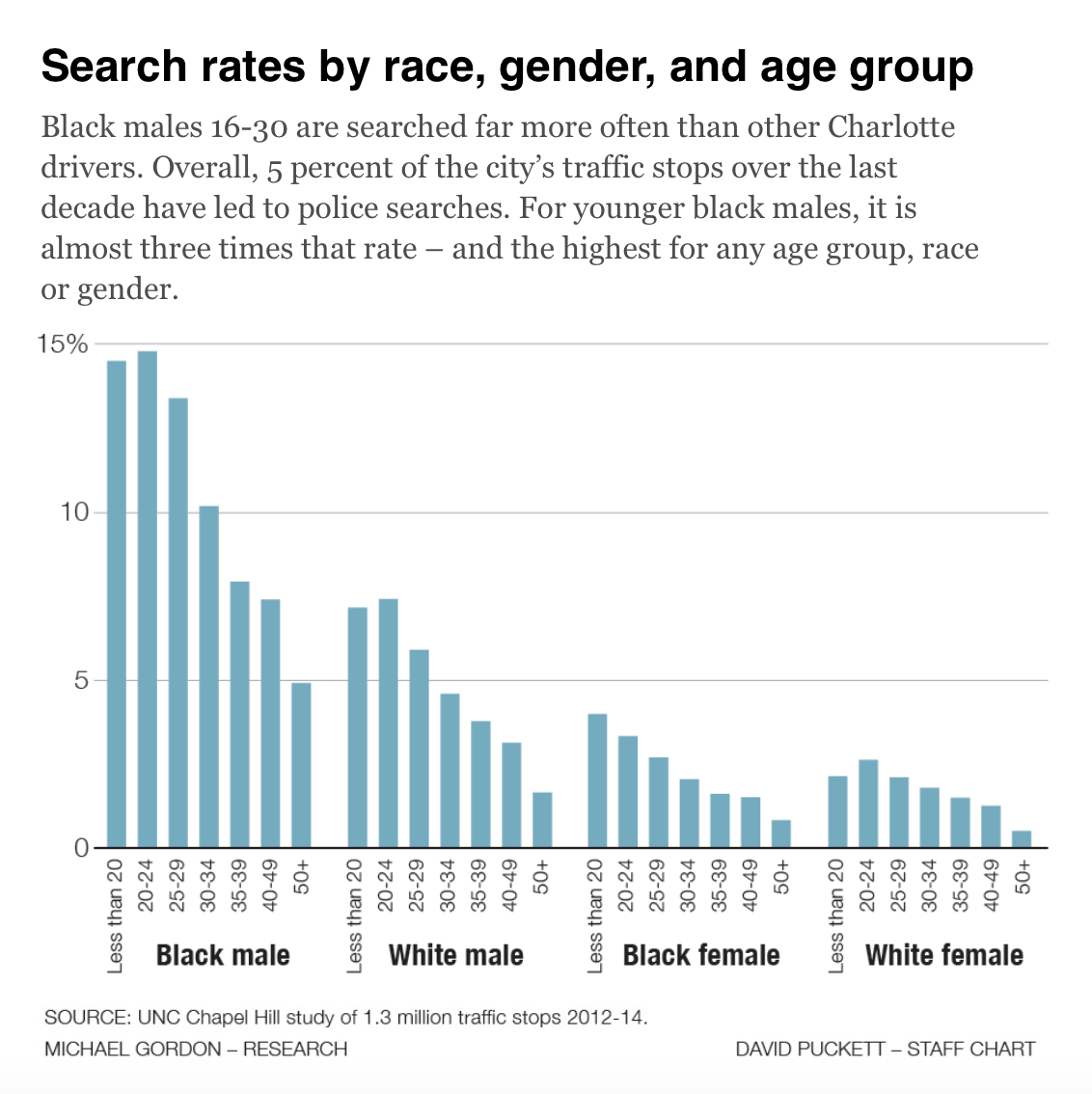

The researchers at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill analyzed more than 1.3 million traffic stops and searches by Charlotte-Mecklenburg police officers for a 12-year period beginning in 2002, when the state began requiring police to collect such statistics. In their analysis of the data, collected and made public by the state’s Department of Justice, the researchers found that black drivers, despite making up less than one-third of the city’s driving population, were twice as likely to be subject to traffic stops and searches as whites. Young black men in Charlotte were three times as likely to get pulled over and searched than the city-wide average. Here’s a chart from the Charlotte Observer‘s report detailing the findings:

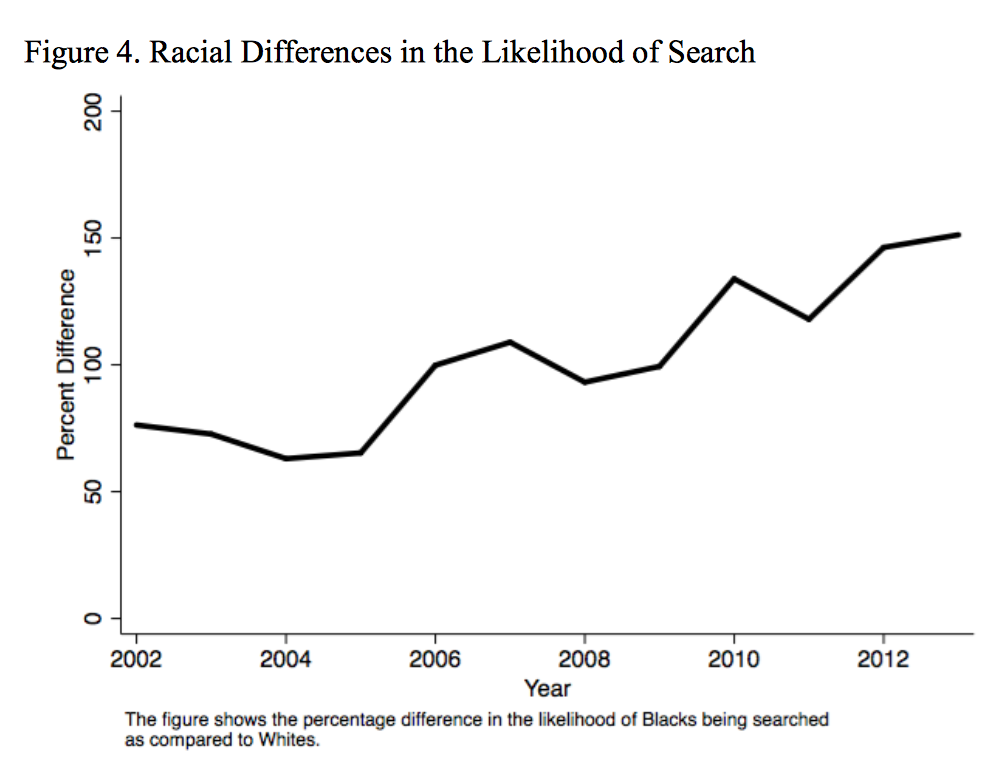

Not only did the researchers identify these gaps: they showed that the gaps have been growing. Black drivers in Charlotte are more likely than whites to get pulled over and searched today than they were in 2002, the researchers found. They noted similar widening racial gaps among traffic stops and searches in Durham, Raleigh, and elsewhere in the state.

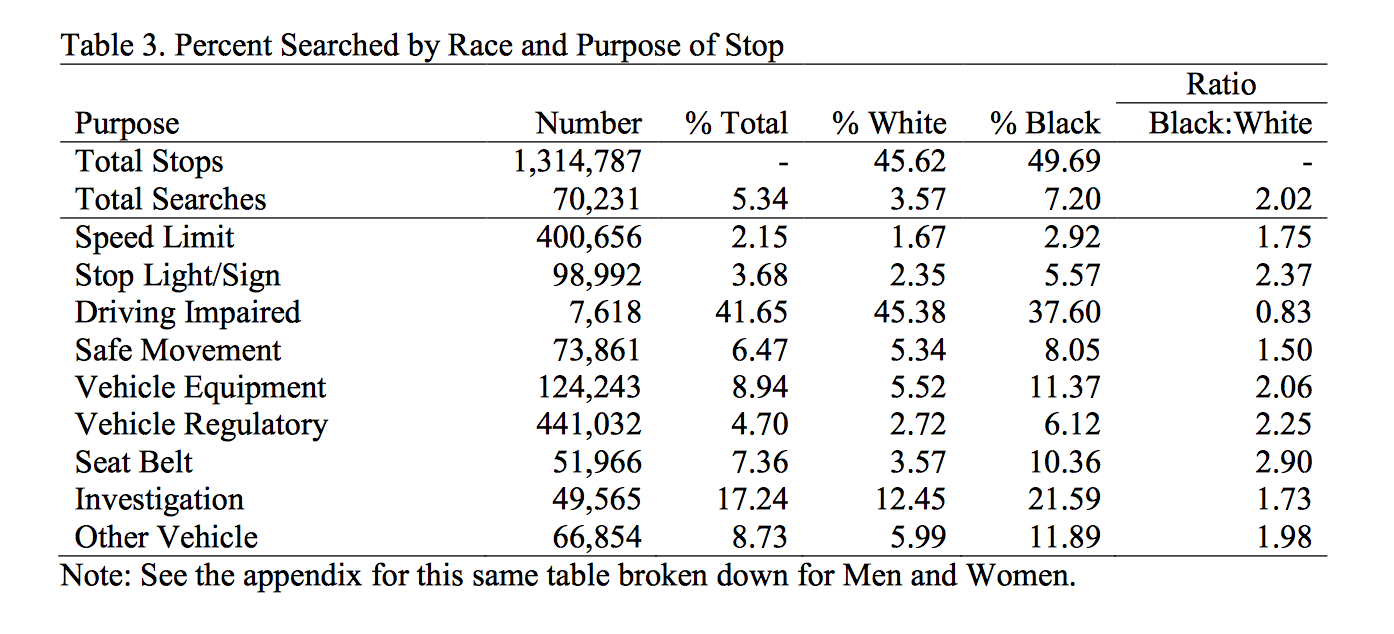

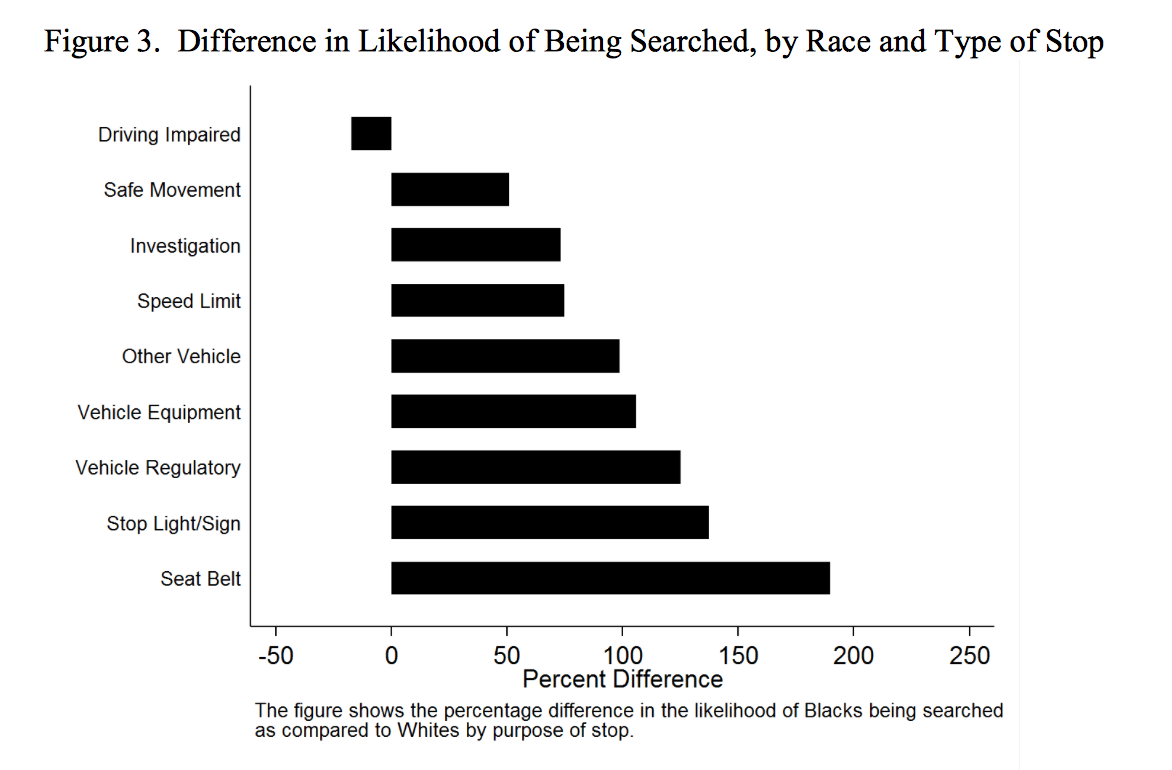

Black drivers in Charlotte were much more likely to get stopped for minor violations involving seat belts, vehicle registration, and equipment, where, as the Observer‘s Michael Gordon points out, “police have more discretion in pulling someone over.” (Scott was stopped in North Charleston due to a broken brake light.) White drivers, meanwhile, were stopped more often for obvious safety violations, such as speeding, running red lights and stop signs, and driving under the influence. Still, black drivers—except those suspected of intoxicated driving—were always more likely to get searched than whites, no matter the reason for the stop.

The findings in North Carolina echo those of a 2014 study by researchers at the University of Kansas, who found that Kansas City’s black drivers were stopped at nearly three times the rate of whites fingered for similarly minor violations.

Frank Baumgartner, the lead author of the UNC-Chapel Hill study, told Mother Jones that officers throughout the state were twice as likely to use force against black drivers than white drivers. Of the estimated 18 million stops that took place between 2002 and 2013 in North Carolina that were analyzed by Baumgartner’s team, less than one percent involved the use of force. While officers are required to report whether force was encountered or deployed, and whether there were any injuries, “we don’t know if the injuries are serious, and we don’t know if a gun was fired,” he says.