Over the past few years Scott Winship has made a career out of scolding liberals for exaggerating the recent growth of economic insecurity, and I’ve learned a lot by reading his critiques. But I find that I always have a problem with his pieces: he simply pushes back too hard in the opposite direction. If there are different measures of some variable, he always picks the one that minimizes the problem. If there are alternate explanations for a trend, ditto. If different datasets say different things, ditto again. The right answer is always the one that makes the problem look the smallest.

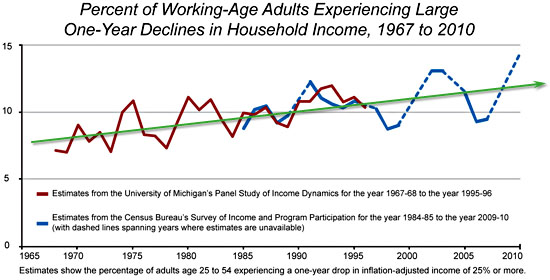

I was reminded of this today while reading “Bogeyman Economics,” a long piece in National Interest whose takeaway is that a careful examination of the data suggests that economic insecurity hasn’t risen much at all in recent years. But Winship’s thumb is invariably on the scale. In his look at income volatility, for example, he reviews some valuable criticisms of previous research. But he also dismisses the use of an alternate dataset without offering much of an explanation and insists that a proper look at the data — which measures the portion of working-age adults who experience a 25% year-to-year income decline — suggests very little change over the years. But look at his own chart:

The number of families with big income drops has “increased only slightly,” he says, and even accounting for cyclical fluctuations “the claims of dramatically increased volatility simply don’t stand up.” But a simple look at the data says different. I added the green line going roughly through the middle of the data, and it shows the number of at-risk families rising from about 8% to 12%. That’s a 50% increase, which is significant by any measure. What’s more, if you look at the trend line going through the peaks, which correspond to economic recessions, the increase is even greater. In other words, the impact of recessions has become larger and larger over the past four decades — exactly the concern of those who write about economic insecurity.

Other examples litter the piece. Maybe some of the income drops in the chart above are voluntary, he suggests, without presenting any evidence that voluntary income losses have risen. He calls a joblessness increase of 3% to 6% between 1968 and 2007 “modest,” even though it represents a doubling. Long-term unemployment is up a lot, he concedes, but hey — it’s a small number of people in absolute terms. A 2% bankruptcy rate per year — up nearly 10x since 1980 — isn’t very much. (And we should be suspicious of the number anyway, though Winship provides no data to suggest why.) Credit card debt has doubled, but that’s OK because it’s only among a minority of Americans. The ranks of those without health insurance has gone up by 12 million, but it’s a small worry because it represents an increase of only 4 percentage points (which looks small on a chart that goes from 0 to 100). And throughout it all, virtually every statistic is tied to medians, even though we should expect that income insecurity has probably grown the most in the bottom third or fourth of the population.

I get what Winship is doing. He believes that horror stories of increased economic insecurity have been exaggerated for political effect, so he’s fighting back. And he makes some good points along the way. But in the end, he just goes too far. His evidence seems so obviously cherry picked that I never know what to trust and what not to trust. After all, in a rich country economic insecurity will never affect more than a smallish portion of the country, which means that even substantial changes can almost always be dismissed as modest in absolute terms. (A 20% increase in a quarter of the population, for example, nets out to an overall increase of only 5%.) By this measure, a rise in unemployment from 6% to 10% — which only affects 4% of the population — is hardly worth noticing. But as we all know, this is actually a sign of a deep and major recession.

“If we are to effectively confront the fiscal and economic challenges of the 21st century,” Winship concludes, “we will need to begin by seeing things as they really are.” I agree. But that goes for both sides. Small but persistent rises in economic insecurity suggest serious problems, especially when they’re happening in the midst of substantial economic growth and show few signs of slowing down. A fair look at the data is fine, but not one that seems to bend over backward time after time to minimize long-term trends that suggest very real problems and very real distress.