Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey testifies before a Senate Intelligence Committee hearing on social media platforms in 2018. Jose Luis Magana/AP

The dietary gyrations of Twitter/Square CEO Jack Dorsey create more fuss than any celebrity I can think of since Oprah in her ’80s-’90s heyday. Over the years, Dorsey has publicly dabbled in veganism (which turned his skin orange); gone paleo (no wheat, lentils, or dairy); advocated drinking only red wine and lemon juice; and promoted a breakfast of salted water mixed with lemon. “The lithe, 42-year-old tech founder has become a one-man Goop,” wrote Nellie Bowles in the New York Times, referring to Gwyneth Paltrow’s brand, through which the actress extols all manner of juice cleanses and eternal-youth elixirs.

Last month, Dorsey set the internet aflame by revealing on a fitness podcast that he very rarely eats: just one meal a day during the week, and nothing but water from Friday till Sunday night. Those five weekly meals consist of “fish, chicken, or steak with a salad, spinach, asparagus or Brussels sprouts,” plus “mixed berries or some dark chocolate for dessert and also… [some] red wine.”

What Dorsey is advocating here is essentially two strict diets, combined: intermittent fasting (those two days sans food) and severe calorie restriction (those other five one-meal days). In an astute Washington Post piece, Monica Hesse noted the very fine—and grotesquely gendered—line between Dorsey’s “biohacks” and clinical eating disorders. About Dorsey’s weekday dinners, Hesse added: “Unless ‘some steak’ is a euphemism for ‘a cow,’ I can immediately tell you that Jack Dorsey is consuming fewer than 1,000 calories a day, which is a diet no nutritionist would recommend.” Indeed, the USDA recommends that an active adult male (Dorsey also cops to a rigorous exercise regimen) take in almost 3,000 calories daily.

All of this left me with two questions: What does research tell us about the health impacts of the two diets Dorsey is mashing up here? And what does it mean for the millions of Americans with eating disorders—and the untold number in recovery from them or prone to them—to hear such a venerated figure extol the virtues of hardly ever eating?

Research is mixed on the benefits of intermittent fasting. One 2017 research review by sports scientists concluded that regular fasts offer “no significant advantage” over simply eating less on a daily basis for losing weight. Another 2017 literature review by University of California at San Diego researchers looked at dozens of animal and human studies on the effects of putting off eating. They concluded that while more research is needed, “intermittent fasting regimens may be a promising approach to losing weight and improving metabolic health for people who can safely tolerate intervals of not eating, or eating very little, for certain hours of the day, night, or days of the week.” But here’s the thing: You may not have to go full @Jack to capture the possible benefits. The researchers added that regular “overnight” fasts—eg, eating only during daylight hours—”may be a simple, feasible, and potentially effective disease prevention strategy.” They note: “Although this hypothesis has not been tested in humans, support from animal research is striking.”

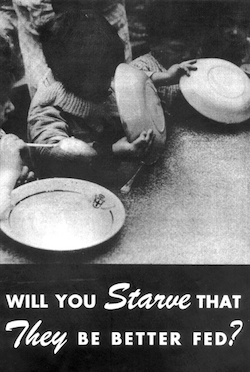

Recruitment brochure cover for the Minnesota Experiment, 1944.

The American Society for Nutritional Sciences

As for severe calorie restriction, we have a rigorous, government-run human experiment to turn to: It’s called the Minnesota Starvation Experiment. It happened toward the end of World War II, when US government researchers were anticipating the massive challenge of rebuilding famine-ravaged Europe. To simulate those conditions, the idea was to subject healthy young men to a meager diet, bring them to the point of starvation, and then try out ways of feeding them back to health. Thirty-six healthy young men—many of them conscientious objectors to the war—signed up for the project. They lived in a barracks located in the University of Minnesota football stadium and received a daily ration of roughly 1,800 calories. The participants were expected to walk about three miles—and expend around 3,000 calories—daily. (That is, they were burning 66 percent more energy than they were taking in as food.)

In a 2005 paper, Johns Hopkins researchers rehashed the findings. I don’t foresee the results summarized on a slide in a TED talk about biohacking anytime soon:

The men reported decreased tolerance for cold temperatures, and requested additional blankets even in the middle of summer. They experienced dizziness, extreme tiredness, muscle soreness, hair loss, reduced coordination, and ringing in their ears. Several were forced to withdraw from their university classes because they simply didn’t have the energy or motivation to attend and concentrate.

By the end, most had lost a quarter of their bodyweight, and “many experienced anemia, fatigue, apathy, extreme weakness, irritability, neurological deficits, and lower extremity edema,” the Hopkins authors state. Nor do the subjects’ mental states sound like what tech CEOs have in mind when delivering dietary advice to their workforces:

As semistarvation progressed, the enthusiasm of the participants waned; the men became increasingly irritable and impatient with one another and began to suffer the powerful physical effect of limited food. Carlyle Frederick remembered “noticing what’s wrong with everybody else, even your best friend. Their idiosyncrasies became great big deals … little things that wouldn’t bother me before or after would really make me upset.”

As for the recovery period, the study’s leader, famed dietician Ancel Keys, observed that a slight increase in caloric intake would simply not do. “Enough food must be supplied to allow tissues destroyed during starvation to be rebuilt,” he wrote. He concluded that 4,000 daily calories “for some months” did the trick.

Around 30 million Americans have eating disorders. What can they—and folks vulnerable to such conditions—think of celebrity tech bros’ babbling about how they optimize their productivity by skipping nearly every meal?

Through a Twitter spokesperson, Dorsey himself declined to comment on this question. I asked National Eating Disorders Association CEO Claire Mysko about Dorsey’s latest intervention into the national diet conversation. She called it a “potentially dangerous message,” both for people vulnerable to conditions like anorexia. “There is so much discussion right now in our culture about health and wellness, this diet and that diet,” she said. “It’s difficult messaging for the average person to navigate. But for those who do have these vulnerabilities, it’s particularly toxic.”

Mysko added that she hoped the backlash to Dorsey publicizing his diet fads would open space for dialogue about the largely hidden problem of eating disorders among men. Despite the “stereotype that eating disorders only occur in women, about one in three people struggling with an eating disorder is male,” NEDA’s website states.

Altogether, at least 10 million men have full-on conditions like bulimia and anorexia—and the real number is probably higher. “Unfortunately there’s so much shame and stigma, and so many men go untreated,” Mysko said. And she added that “disordered behaviors” that don’t rise to the full level of a diagnosable condition—including occasional binge eating, purging, laxative abuse, and fasting for weight loss—are nearly as common among men as they are among women.

Just as an impossibly skinny ideal has haunted many women for generations, men are more and more pressured by the slim, sculpted, six-pack body type, she says. And high-profile fads among the Bay Area techno-elite—paragons of success in our culture—ramp things up still further. “In Silicon Valley, there’s a focus on productivity and purity and achievement that’s linked to a restrictive diet,” she says. Such glorification of the “virtues of self-control and self-denial” is “really problematic for people who are struggling or at risk” for eating disorders.

So when our overlords credit their business triumphs to their workout obsessions and radical diets, they probably don’t help the nation’s festering body-image problems any more than supermodel Kate Moss did, with her famously triggering (and since withdrawn) statement that “nothing tastes as good as skinny feels.”

For those struggling with an eating disorder, the National Eating Disorders Association Helpline is 800-931-2237. For a 24-hour crisis line, text “NEDA” to 741741.