You say tomato: Hillary Clinton scores some fresh produce at a New Hampshire farm. <a href="http://www.apimages.com/metadata/Index/DEM-2016-Clinton/68e3e78adf124563ad4ebf8f0c85562d/19/0">Associated Press

The 2016 presidential election is hurtling into unknown territory, as candidates blessed by party elites fight for their political lives while insurgents suck up all the oxygen. But one time-tested electoral tradition remains in place: Everyone—from the socialist Vermont Jew with the excellent Brooklyn accent to the xenophobic billionaire reality-TV star—is largely ignoring food and farm policy on the stump.

Meanwhile, slow-motion ecological crises haunt the country’s main farming regions, and diet-related maladies generate massive burdens on the US health care system. Over the next three frantic weeks—with five debates and more than two dozen primaries—the two major-party candidates may well emerge. If I were a debate moderator or a reporter on the trail, here are some questions I would ask them:

1. Bolstered by tens of billions of dollars of crop and insurance subsidies over two decades, farms in the US Corn Belt—the former prairies occupying much of the upper Midwest—churn out the feed that drives the country’s meat industry. They also produce the feedstock for ethanol, which accounts for about 10 percent of fuel we use in cars. Yet the region is losing the very resource that makes all this bounty possible: Its precious store of topsoil is disappearing much faster than the natural replacement rate—a trend that will likely accelerate as climate change proceeds apace. And all of that runaway dirt carries agrichemicals into waterways along with it, fouling tap water in Des Moines, Columbus, Toledo, and countless other communities and feeding a monstrous dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico.

A growing body of research suggests that diversifying crops—growing other stuff besides just corn and soybeans, including everything from wheat and oats to vegetables—could go a long way to reversing these catastrophes. As president, how would you push farm policy to reward soil- and water-friendly farming practices in the heartland?

2. Meanwhile, in the country’s fruit and vegetable belt, a different kind of water crisis unfolds. Drought persists in California—the source of 81 percent of US-grown carrots, 95 percent of broccoli, 86 percent of cauliflower, 74 percent of raspberries, 91 percent of strawberries, and nearly all almonds and pistachios, plus a fifth of US milk production. In the state’s massive Central Valley, agriculture has gotten so ravenous for irrigation water that its aquifers have been declining steadily for decades. Meanwhile, the Imperial Valley in California’s bone-dry southeastern corner provides about two-thirds of US winter vegetables. These crops are irrigated by water diverted from the declining Colorado River, putting the region’s farms into increasing competition with the 40 million people who rely on the waterway for drinking water. For decades, federal policy has encouraged California’s produce dominance by investing in irrigation infrastructure and through sweetheart water deals with well-connected Central Valley growers. Some observers—okay, me—have called for a “de-Californication” of US fruit and vegetable production in response to these crises. How would your administration respond to California’s declining water resources in the context of its central position in our food system?

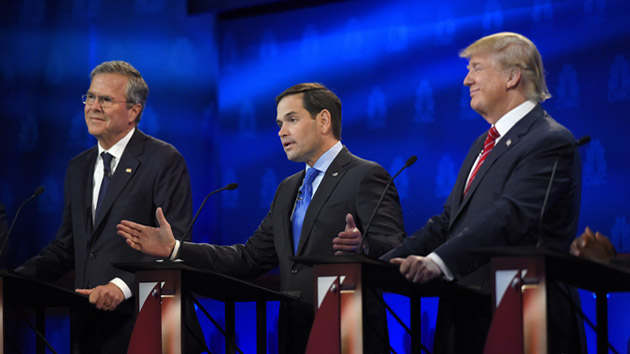

3. Republican candidates have focused largely on the alleged scourge of undocumented immigrants from points south, while the Democratic debate has hinged on income inequality. The two issues intersect on our plates, through the hidden labor required to feed us. According to the US Department of Agriculture, about 70 percent of workers on US crop fields come from Mexico or Central America, and more than 40 percent of them are undocumented. Median hourly wage: $9.17. In restaurants, where the median hourly wage stands at $10, tips included, around one in six workers are immigrants, nearly double the rate outside the restaurant industry. After spasms of union busting in the 1980s, the meatpacking industry, too, relies heavily on immigrants—and pays an average wage of $12.50 per hour. How would you act to improve wages and working conditions for the people who feed us?

4. Under Hillary Clinton, the US State Department conducted a “concerted strategy to promote agricultural biotechnology overseas, compel countries to import biotech crops and foods they do not want, and lobby foreign governments—especially in the developing world—to adopt policies to pave the way to cultivate biotech crops,” a 2013 Food & Water Watch analysis of diplomatic cables released by WikiLeaks found. Meanwhile, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development has called for a different approach to agricultural policy: a “rapid and significant shift from conventional, monoculture-based and high external-input-dependent industrial production towards mosaics of sustainable, regenerative production systems.” Would your administration continue to promote biotech crops around the world and lobby foreign governments to accept them? Why or why not?

5. For decades, US antitrust authorities have watched idly as huge food companies gobble each other up, grabbing ever larger shares of food and agriculture markets. According to Mary Hendrickson, a rural sociologist at the University of Missouri, just four companies (not the same ones in each case) slaughter and pack more than 80 percent of US beef cows, 60 percent of the country’s pigs, and half of its chickens. After last year’s merger of chemical behemoths Dow and Dupont, three companies—DowDuPont, Monsanto, and Syngenta—will soon own something like 57 percent of the global seed market and sell 46 percent of pesticides. Since then, state-owned China National Chemical Corp. has bought Syngenta. Early in his administration, President Barack Obama initiated serious investigations of these highly consolidated industries, responding to farmers’ complaints of uncompetitive markets. After much buildup, these efforts ended with a thud. How would your Department of Justice look at consolidation in ag markets—and would you consider antitrust action to break them up?

6. According to a 2013 report from the Union of Concerned Scientists, annual US medical expenses from treating heart disease and stroke stood at $94 billion in 2010—and were expected to nearly triple by 2030, driven largely by diets dominated by hyperprocessed food. The report concluded that if Americans followed USDA recommendations for daily consumption of fruits and vegetables, 127,000 lives and $17 billion in medical expenses would be saved annually. What’s the proper federal role for convincing people to eat healthier—especially people of limited means? (Hat tip to Food Tank, which asks nine other excellent questions.)