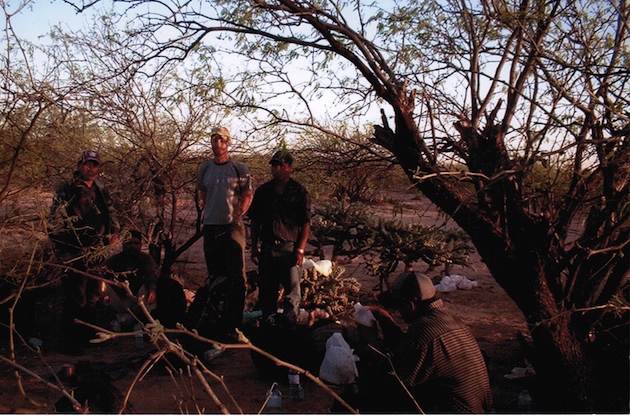

Author Seth Holmes, second from left (standing), preparing to sneak across the US/Mexico border with Triqui migrant farm workers. Courtesy of University of Califiornia Press.

For most anthropologists, “field work” means talking to and observing a particular group. But for Seth Holmes, a medical anthropologist at the University of California-Berkeley, it also literally means working in a field: toiling alongside farm workers from the Triqui indigenous group of Oaxaca, Mexico, in a vast Washington state berry patch. It also means visiting them in their tiny home village—and making the harrowing trek back to US farm fields through a militarized and increasingly perilous border.

Holmes recounts his year and a half among the people who harvest our food in his new book Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies. It’s a work of academic anthropology, but written vividly and without jargon. In its unvarnished view into what our easy culinary bounty means for the people burdened with generating it, Fresh Fruit/Broken Bodies has earned its place on a short shelf alongside works like Tracie McMillan’s The American Way of Eating, Barry Estabrook’s Tomatoland, and Frank Bardacke‘s Trampling Out the Vintage: Cesar Chavez and the Two Souls of the United Farm Workers.

I recently caught up with Holmes via phone about the view from the depths of our food system.

Mother Jones: What sparked your interest in farm workers—and how did you gain access to the workers you cover in the book?

Seth Holmes: I’ve always been interested in Latin America. My parents took me to southern Mexico as a kid, basically once or twice a year to volunteer at an orphanage there. I started looking into working with migrant farm workers in the Central Valley of California, and had a pretty hard time getting direct access to them—the farm owners weren’t cooperative. Then I went up to Washington state to visit a social worker friend who was working with this group of indigenous farm workers from Mexico. He also introduced me to a Methodist pastor whose parishioners included the owners of the farm where the workers worked. And with those connections in place, I was able to get access both to the workers and the farm itself.

MJ: Talk me through the scope of your project.

SH: I did full-time field research for 18 months, starting in 2004. I started with them up in Washington state, living in the labor camp and picking berries with them and then moved to central California with them. When we got to California, we were homeless for the first week, living out of our cars until we could find an apartment that would rent to people without a credit history. And then 19 of us moved into a three-bedroom apartment and then trimmed vineyards whenever we could get work. Then we moved down to their home village up in the mountains of Oaxaca, Mexico, and then I crossed the border with them into Arizona, on their way back to Washington.

MJ: What sort of conditions were you seeing in the fields?

SH: If you don’t pick the minimum weight you get one chance to show you can do it, and then if you can’t do it a second time then you’re fired and kicked out of the camp. They ended up making an exception for me—they kept me on even though I wasn’t able to pick the minimum, because I was kind of interesting to have around and didn’t fit in. I was the one white guy who worked in the field.

MJ: What sort of wages were folks making?

SH: They were paid 14 cents per pound of de-leafed, ripe strawberries. At the time minimum wage was $7.16 in Washington, so they had to pick at least 60 pounds of strawberries each hour. Strawberries last maybe two months, blueberries last maybe another two months, and then most of the farm workers then moved to the Central Valley of California where they looked for work and there isn’t very much work in the winter. All told, they made between $5000 and $7000 per year.

MJ: What it was like in the village in Oaxaca?

SH: The village was in the mountains, in a really arid place. They grow all different kinds of corn, as well as beans and greens. They’re basically subsistence farmers, using their ancestral lands to grow food for themselves and for their families, and then they sell [surplus] corn in the nearby town so they can buy the uniforms for the public school and things like that. But over the last 20 or so years, the area has been becoming more economically depressed. In my understanding, a large reason for that is the North American Free Trade Agreement, which makes it illegal for any signatory country, including Mexico, to have tariffs on produce from other countries. But it allows the relatively wealthy country, the US, to have crop subsidies, which are essentially a hidden tariff.

MJ: Did you find that most families in those villages had someone in the US earning dollars?

SH: Definitely, at least one person. And you could sort of tell, based on their houses, how many family members were in the US. Some of them had dirt-floor houses, and some of them had concrete houses that were being added onto with money they were being sent back from the US.

MJ: What sort of differences in diets did you note between labor camps in the US and in the Oaxacan villages?

SH: In the village, they mostly ate what they grew. They would make homemade tortillas from the corn they grew, they’d eat a lot of greens that they grew or that they would just pick from the nearby forest, they would eat beans, and then sometimes they would buy eggs from neighbors, or they would keep some chickens for eggs. That was basically their diet.

In the US, on pay day often they would go to a fast-food restaurant to kind of celebrate—they’d get burgers and fries. Most of the rest of the week they would get food from churches or soup kitchens. One of the families liked to go out to a cheap Chinese buffet place, because you could get a lot of food for a small amount of money.

MJ: Talk me through the passage north over the border. Start with the “coyote”—the person who facilitates the illicit crossing.

SH: The people I was with were lucky, because unlike people from Central America, they came with a coyote from their home village. So their coyote is usually someone they can trust to have their best interest at heart. Whereas people from Central America who come to the northern border of Mexico have to go search around for a coyote, and don’t really have any background with any of the people to know who’s trustworthy and who might be kidnapping them.

MJ: How much did the passage cost—what was the going rate for a coyote?

SH: At that point, it was about $2,000. Now it can be up to $4,000 because of all the changes at the border [i.e., ramped-up efforts on the US side designed to keep undocumented migrants out]. And of course, the journey has gotten dangerous [since 2004]. A recent University of Arizona study showed that the number of people dying in the desert each year [during the passage] has gone up even though the number of people trying to cross has gone down.

MJ: So how did it go for you and your friends?

SH: We rode a bus from the town right next to where they live all the way up to the the US/Mexico border—something like 40 hours. A few times a day we were stopped at a kind of military check point, and each time the bus driver would announce over the intercom that everybody should say that they’re going to Baja, California, to pick tomatoes so that then there wouldn’t be extra time wasted answering questions about border crossings. But each time he made that announcement he would also point at me and say you have to say that you’re going to Guadalajara or Hermosillo or whatever, kind of the nearest tourist town so that they wouldn’t think that I was kind of hitch hiking.

We crossed the border on foot, starting at sunset through the desert into Arizona. I couldn’t tell the difference between Sonora and Arizona—they looked the same. We hiked through, under, and over 17 or so fences—some wooden, some barbed wire. We’d rest in dried-up creek beds, because we know in a creek bed there weren’t going to be cacti. We ripped open trash bags and used them as blankets. At one point, we slept while our coyote went to make contact with the person who was supposed to drive us past the second border checkpoint into the US.

MJ: Did you ever feel you were in danger?

SH: Definitely. It was terrifying. You can’t use head lamps or flashlights, because you don’t want to be seen. So you’re moving through the desert with cacti, and we ran into at least one rattlesnake, and we know that there are scorpions. Anytime you see anyone off in the distance, you knew that they could be other people to cross the border, or they could be people who are trying to rob you, because they know that everyone going through the desert has a bunch of cash on them, for the trip and for their coyote and things like that. This went on for something like 15 hours.

MJ: In the whole progression of your project—from farm work to this awful crossing and back—what sort of both physical and psychological toll did you see on these people who are essentially putting food on our tables?

SH: There’s this sort of unspoken transaction going on, where the workers endure the crossing and then start working seven days a week bent over, so that their families can get by in Mexico. Most of them develop bad knees, backs and hips, some of them have problems from pesticide exposure, and pregnant women more often will have problems with premature birth or birth defects. And everyone kind of expects not be able to work a full career because the work is so difficult on their bodies—that after 10 years or so their backs will be so bad that they won’t be able to do it any more. And part of the transaction is that they’re giving up their bodily health so that the rest of us can shop at grocery stores and farmer’s markets and have access to exactly what public-health researchers and doctors tell us we need to be healthy: fresh fruits and fresh vegetables.