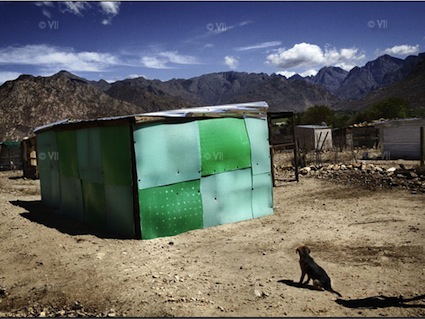

A squatter camp sits against backdrop of vineyards and mountains in South Africa's wine country.<a href="http://www.hrw.org/features/human-rights-conditions-south-africa-fruit-wine-industries">Marcus Bleasdale</a>/Human Rights Watch

I’ve seen it: People who are extremely fussy about the food they put in their mouths—shopping at farmers markets for veggies and meat and looking for Fair Trade labels on tropical goods—nevertheless choose wine based on whatever has the quirkiest label at the price point they’re comfortable with.

But just as much as tomatoes or pork chops, wine is an agricultural product. Grapes are grown on real land and tended by real people—and marketed by corporate flacks who know how to paint a lovely picture.

Here’s a passage from one such marketing professional’s proposal for pitching the (increasingly fashionable) wines of South Africa to US consumers:

“Think of how people see most of the wine producing regions of the world. California and France are old hat. Australia and New Zealand are boring little colonies. Germany’s wine region isn’t that interesting from the consumer’s perspective either. But Africa has everything: immaculate vineyards, sunshine, a diverse people, jazz, great food and a laid-back lifestyle. The place is beautiful, absolutely beautiful. No other continent triggers the imagination the way Africa does.” Indeed, local exporters are now using images of alluring African models, sipping red wine, to sell their product—creating an enviable market profile of ethnic spice overlaid against the nation’s claim on 350 years of winemaking.

And here’s Human Rights Watch with a rather more sober depiction of South Africa’s vineyards, from its new report, Ripe with Abuse: Human Rights Conditions in South Africa’s Fruit and Wine Industries (PDF).

Every year, millions of consumers around the world enjoy South African fruits and the renowned wines that come from its vineyards. Yet the farmworkers who produce these goods for domestic consumption and international export are among the most vulnerable people in South African society: working long hours in harsh weather conditions, often without access to toilets or drinking water, they are exposed to toxic pesticides that are sprayed on crops. For this physically grueling work, they earn among the lowest wages in South Africa, and are often denied benefits to which they are legally entitled. Many farmworkers confront obstacles to union formation, which remains at negligible levels in the Western Cape agricultural sector. Farmworkers and others who live on farms often have insecure land tenure rights, rendering them and their families vulnerable to evictions or displacement—in some cases, from the land on which they were born.

According to Human Rights Watch, the minimum wage for farm workers in South Africa amounts to about $46 per week—less even than the minimum for the other worst-paid workers in the nation, domestic maids. Housing conditions are deplorable—workers and their families are often shunted into temporary structures, abandoned pigsties, even former outhouses—and tenure is uncertain. Union participation is minimal, and vigorously fought by the farm bosses. Pesticides are used widely—and workers are routinely denied sufficient protection from them.

Historically, workers in South Africa’s wine grape fields were paid partially in wine—an advantageous arrangement for the vineyard owners, but a bad trade for workers, because it led to widespread alcohol-abuse problems. The post-apartheid government banned the practice, and instances of it are now very rare, Human Rights Watch reports. But its legacy lives on. Alcohol abuse is “rampant” among workers, and the region suffers from “one of the highest levels of fetal alcohol syndrome in the world.”

Race remains deeply problematic in the post-apartheid wine industry. Farmers in South Africa’s wine industry are increasingly diverse, Human Rights Watch reports, with government programs creating opportunities for non-white farm owners. “But the majority of commercial farms in [wine country] are still owned by white South Africans,” says the report, and the workforce is largely black.

Now, US readers should not read this with any sense of superiority. Our own industrial-scale farm fields are characterized by low pay, racial stratification, substandard housing, and pesticide abuse. If South Africa’s wine barons want a lesson in how to create even worse conditions for workers, they should look no further than Florida’s tomato fields, as Barry Estabrook shows in his searing, excellent Tomatoland.

But the report should remind us that our wine comes from somewhere. We should pay more attention to what we sip along with our local, organic veggies and pasture-raised meat.

Here’s the video Human Rights Watch made to accompany its report: