Israel Vargas/High Country News

This story was originally published by High Country News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Lightning strikes in a dry forest and starts a wildfire. It’s a hot, windy day, and the embers quickly spread. Smoke rises, and it’s detected, sometimes by satellites, lookouts or people who call 911. Reports bombard an interagency dispatch center: There’s a new start, and it needs firefighting resources, fast.

The wildland fire dispatchers who respond are a critical link in the fast-moving series of decisions needed to begin battling a blaze. When a fire sparks, they’re the ones responsible for figuring out who’s nearby to fight it, and sending resources where they need to be as quickly as possible. “A good dispatcher is make-or-break if you want to keep a small fire small,” said Rachel Granberg, a wildland firefighter in Washington. (Granberg asked to keep her employer private because she could lose her job for identifying it in the media.)

When a new blaze needs air tankers and helicopters dropping retardant and water, aircraft-certified dispatchers coordinate what’s flying where, so the aircraft don’t collide. If firefighters get hurt, dispatchers send medical help to often-remote scenes. Once a fire is underway, dispatchers relay crucial information to and from the fire line, including wind, humidity and temperature forecasts that can determine fire behavior and influence planning and safety on the ground.

But the job is stressful, and sometimes traumatic, amid today’s larger fires, longer fire seasons and too few colleagues. The US Forest Service conducted a survey of dispatchers in Oregon and Washington—Region 6 in agency lingo—in the fall of 2022. The survey found that “dispatch is experiencing problems that compromise their own health and safety” as well as “the health and safety of other firefighters,” according to internal presentation materials obtained by High Country News this spring. When dispatching resources are spread thin, it can impair everything from implementing and monitoring prescribed burns to suppressing active wildfires.

“You have to understand the problems before you can try and address solutions,” said Matt Holmstrom, a regional risk management officer for the Forest Service who oversaw the survey. Holmstrom, a hotshot for nearly two decades, is the agency employee tasked with trying to reduce accidents and injuries in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska.

The survey included lengthy interviews with 104 of the 189 dispatchers at the 14 largest call centers in Region 6. Call centers are often staffed by dispatchers from different agencies, so the survey included dispatchers from federal agencies, including the Bureau of Land Management and Bureau of Indian Affairs as well as the Forest Service, along with state agencies such as the Oregon Department of Forestry and Washington Department of Natural Resources.

HCN filed a Freedom of Information Act request for the presentation of the survey results and interview transcripts, but the Forest Service denied it, saying releasing them would compromise its decision-making ability and prematurely announce proposed policies. (HCN appealed the denial and is awaiting a response.) The agency did, however, share emails about the survey’s planning, including one from Alex Robertson, the director of fire, fuels and aviation for the Forest Service in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, to regional leaders from the Forest Service and other agencies. Robertson wrote, “We have long recognized that our margins for error are so slim now due to vacancies and increases in workload.”

While some centers in the West are adequately staffed, the survey identified recruitment, retention and vacancies as major problems in Region 6. Over half of respondents said they had little to no work/life balance; many felt forced to take on overtime work, struggled to take time off and did not receive adequate breaks. A BLM dispatcher with more than 10 years of experience, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retribution by his employer, said that experienced dispatchers are overworked and often quit, leading to heavy burdens on those who remain. “It’s a vicious cycle,” he said. Shifts can be up to 16 hours long or more—that dispatcher’s personal record is over 24—during fire season. “I don’t know how long that pace is sustainable,” Holmstrom said.

A source familiar with the survey said that it identified concrete problems stemming from staffing shortages. In one case, a dispatcher with known gallbladder issues didn’t have enough time to step away to use the restroom and later needed emergency surgery. The survey also found at least one dispatch center on the verge of collapse, with dispatchers threatening to quit because they were short-staffed, overworked and overlooked.

The dispatcher shortage also impacted wildfire camps this summer. At times, managers send dispatchers out to fires to help with communications. During one large fire that threatened homes in western Oregon in August, however, there were no extra dispatchers to send into the field. A medical unit leader, who asked not to be named because they were not authorized to speak with the media, was pulled away from their duties and sent into the communications tent to operate radios instead.

The majority of survey respondents also noted the mental health challenges prevalent among dispatchers, including burnout, substance abuse and suicide. A Forest Service dispatcher in California, who asked to remain anonymous so that she could speak freely, said dispatchers aren’t always included when mental health resources are offered to firefighters after traumatic incidents. Those times include instances when firefighters have died during her shift. “Dispatch is a lot of times overlooked,” she said. Overhearing a firefighter fatality and a firefighter suicide are things that, she said, “I’ll never forget.”

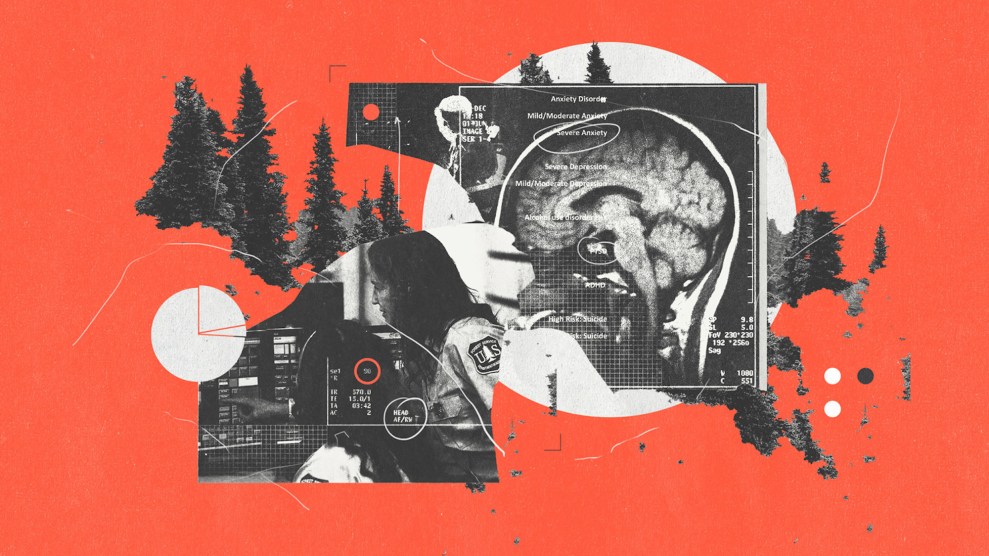

Outside research confirms wildland fire dispatchers’ struggles nationwide. Robin Verble, a professor and director of the Missouri University of Science and Technology Ozark Research Field Station, led a recent research report on dispatcher well-being, in collaboration with several others, including Granberg, the Washington firefighter. Of the 510 dispatchers who responded, 10 percent were considered at high risk for suicide—compared to .3 percent of the general population. “It’s a shocking and very sad statistic that needs more examination,” Verble wrote to HCN in an email. Seventy-three percent of the surveyed dispatchers had mild to severe depression, compared to 18.5 percent of the general population. Signs of post-traumatic stress disorder—33 percent—were almost five times higher than for the general population.

Dispatchers work in a high-stress environment, Verble said in an interview, and “they’re experiencing really high rates of emotional and mental strain as a result.” One anonymous respondent told Verble’s team, “Many of us are total train wrecks.” Another said, “You listen to enough people dead or dying, it will never go away.” Verble’s study also found that dispatchers struggle with physical health problems—including eyestrain, headaches and backaches—from long, stressful shifts in confined quarters that often lack ergonomically appropriate equipment.

Dispatchers want adequately staffed centers so they don’t have to repeatedly work 16 or more hours a day, missing family dinners in the short term and risking burnout in the long run. They say better pay would help recruit and retain more dispatchers. An average Forest Service dispatcher’s base pay is roughly $15 to $20 an hour. “It’s going to continue to be hard to recruit with the perception that we pay less than McDonalds,” a slide from the Region 6 presentation reads.

The 2021 Infrastructure Law provided temporary pay raises for Forest Service wildland firefighters, but it only included dispatchers who have direct firefighting experience. And even those increases were set to expire at the end of September. According to the advocacy group Grassroots Wildland Firefighters, the recently introduced federal Wildland Firefighter Paycheck Protection Act would effectively result in dispatch center managers getting a pay cut, because it would preserve only a portion of the temporary raises. Other benefits are up in the air: Whether dispatchers are included in a new wildland fire job series that the Interior and Agriculture departments are developing will determine whether they have access to retirement benefits.

Being left out of conversations about pay exemplifies a larger problem—a lack of recognition and respect. Dispatchers said they feel undervalued. As one anonymous dispatcher told Verble’s team, “We are dealing with just as much shit, if not more, than the folks on the line. Take care of us. That is all we ask.” Money alone can’t fix cultural issues, Robertson acknowledged in one of the released emails. “We know this is not a funding issues (sic),” he wrote. “It is much deeper than that and will take years to build back our dispatch organizations.”

Regional and national Forest Service leaders have been briefed on the survey results, Holmstrom said, and some small changes are already underway. Some dispatchers have received additional leadership training to help their teams during stressful situations, and more centers are now sharing training resources to bring dispatchers up to speed more quickly when they fill short-term roles.

But that may not be enough. The agency itself admits, in the survey results presentation, that the creation of stress first aid materials tailored for dispatchers—meant to help them understand and recover from stress—and a commitment to following existing stress management protocols after traumatic events are urgently needed. And over 60 percent of the dispatchers Verble surveyed said they’d consider quitting if they aren’t included in a permanent pay bump or access to retirement benefits. The Forest Service dispatcher in California feels the same; despite receiving a recent raise, she feels the weight of her challenging job. “I kind of have a love-hate (relationship with it),” she said. “I love being a dispatcher, but there’s also times when it’s stressful. It’s like, ‘What am I doing? Is this worth it?’”