Viviane Moos/CORBIS/Corbis/Getty Images

This story was originally published by Inside Climate News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Morgen Bromell, a web designer in Brooklyn, had plans to visit their cousin in Los Angeles at the end of the summer, but last week air quality in New York City was so bad they decided to move their flight earlier to escape the smoke. “I called [Delta] and said my asthma is really terrible, can I please change my ticket?”

By the time Bromell finally left New York City, they’d had a migraine for two days, and their asthma was so bad they had to wear a mask indoors.

They were not alone. Last Wednesday, New York City hospitals experienced the highest number of ER visits for asthma-related conditions for all of 2023. That same afternoon, the city was choked by abnormal levels of wildfire smoke from Canada, reaching 366 on the air quality index—24 times the World Health Organization recommended exposure guideline. It briefly had the worst air quality of any city in the world.

While exposure to wildfire smoke has been linked to health conditions ranging from cardiac arrest to preterm birth, those with asthma are the most obviously and quickly affected. And not all communities have the same rate of people suffering from asthma. Poor, Black, and Indigenous communities are more likely to have the disease.

Historically, Black communities have been pushed to live in neighborhoods with fewer green spaces and more hazardous environmental exposures, which have been shown to trigger asthma. In 2020, one paper found rates for emergency department visits due to asthma were 2.4 times higher in historically redlined neighborhoods in California compared to those that were not redlined.

The same trends plague New York. Northern Manhattan, and the South Bronx are typically responsible for a large proportion of asthma emergency room visits and hospitalizations, according to Columbia Public Health. Last Wednesday, the Bronx represented around 27 percent of the asthma-related ER visits, despite having only 16 percent of the population.

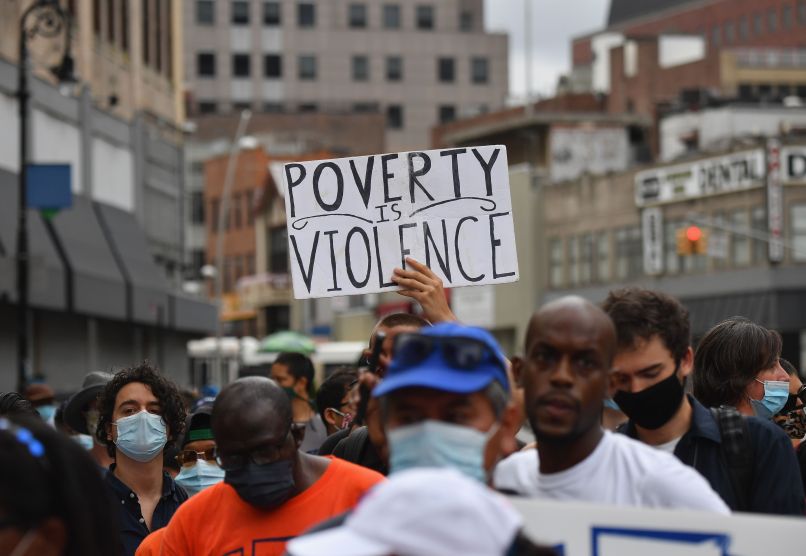

“Breathing fresh air and living in a place that provides healthy outcomes should not be granted or not granted because of either your economic status or the color of your skin,” says Mychal Johnson, an advocate for environmental justice and a cofounder of South Bronx Unite. “We see the disparities very clearly in New York City, where white communities have better access to parks and clean air and green space.”

In New York, children living in the Bronx have higher rates of asthma-related ED visits and hospitalizations compared with all other boroughs. Moreover, the percentage of people who have had an asthma attack in the past 12 months in New York’s poorest neighborhoods is twice that of the wealthiest ones, according to the 2020 Community Health Survey. These communities often live in lower-quality housing, which can make exposure to wildfire smoke outside even worse.

Asthma is an inflammatory disease of the airways (or the pipes that carry oxygen all the way to the lungs); when people with asthma breathe wildfire smoke, it can trigger inflammation and exacerbate their symptoms. Last year, one review of several studies found emergency department visits for respiratory symptoms tend to increase by 10 percent to 30 percent during smoky days, but asthma visits can increase up to 100 percent.

Wildfire smoke carries a handful of different pollutants, like carbon monoxide, ozone, nitrogen dioxide and fine particulate matter (PM2.5). While some of these pollutants can also originate in other industrial or combustion processes, like from cars burning fuel, researchers have found PM2.5 originating from wildfires can be three to four times more toxic for the respiratory system than other types of urban pollution. They have also found PM2.5 from wildfire smoke increases ER visits for respiratory symptoms more than PM2.5 from other pollution sources.

Low-quality housing, which can have leaky roofs or mold contamination, can also trigger or exacerbate respiratory diseases, and is less effective at keeping the polluted air out. In 2021, one study found that in new buildings, only 30 percent to 40 percent of the polluted air gets inside, while in older buildings, where marginalized communities are more likely to live, it can be more than half.

Besides being more exposed to pollutants, which increases the odds of developing asthma, Black communities also live with more stress than white communities and have less access to the healthcare crucial for treating asthma, said Katherine Pruitt, the national senior director for policy at the American Lung Association. “Controlled asthma isn’t the problem, it’s asthma symptoms and asthma attacks, and that really is a function of having regular healthcare,” she says.

From 2016 to 2021, 87.3 percent of U.S. counties experienced an increase in the number of days they were exposed to heavy wildfire smoke, a recently published study found. And this is likely to keep increasing.

“All the papers I have seen have suggested that things are likely to get worse, which is super unfortunate, and I hate to be the bearer of bad news,” said Brooke Lappe, a PhD student in the environmental health program at Emory University and one of the authors of the paper.

As that happens, housing inequalities are one of the things that will become crucial to address. “We talk about sheltering in place, but if your home, the place where you stay all the time, if it’s an older building and hasn’t been repaired, a lot of that wildfire smoke could be getting inside, and you are being exposed,” said Neeta Thakur, a pulmonary physician at the University of California San Francisco. Moreover, these events often coincide with heat waves, and if people don’t have air conditioning, the recommendation to close the windows is hard to follow, she added.

Beyond housing policy, Pruitt said there is a lot governments can do to improve air quality in schools, strengthen air pollution regulations and design policies to protect outdoor workers. “It’s really incumbent on all of us to do what we can as fast as we can to tackle the forces that are worsening climate change, so that we can try to reverse the trend that we are seeing,” she said.