Nina Riggio/High Country News

This story was originally published by High Country News and The Nevada Independent and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

In the final days of 2019, Ches Carney noticed something strange on the bulletin boards at the northern Nevada gold mines where he had worked for nearly three decades. Stores in the nearby town of Elko were playing holiday music, but Carney was upset: The labor union documents, normally posted to bulletin boards, had disappeared.

As a union steward for the International Union of Operating Engineers Local 3, he advocated for his co-workers in disputes with the company. Near the end of the year, the name on Carney’s paycheck changed from Newmont, one of the world’s largest metal miners and an operator of several unionized mines in the area, to something different: Nevada Gold Mines. When Carney confronted a supervisor about the missing union documents, he said he was essentially told that the union was no more and to get over it. The union, which first organized Newmont workers in 1965, negotiated a new contract for about 1,300 production and maintenance workers in early 2019. But by the end of that year, management stopped recognizing it. There was a new boss in town.

Carney, now 66, did a bit of everything as a process maintenance technician—welding, fabrication, examining grease bearings and fixing crushers—as part of a team of four working across a 25-mile area that sits atop a geologic formation known as the Carlin Trend. The Carlin Trend was created by upsurges of magma that left sediment rich with metal deposits near the earth’s surface. Today, this part of northern Nevada is one of the world’s largest gold-mining regions, the spine of the local economy. Its history includes a decades-long rivalry between two of the largest mining companies in the world: Newmont, Carney’s former employer, and Barrick Gold Corp. In the months before Carney’s paychecks changed, the negotiations that led to the creation of Nevada Gold Mines would reshape not only the regional economy, but potentially the entire global gold industry. Barrick and Newmont decided to combine nearly all their Nevada mines and water rights into a single newly formed company. Barrick walked away with a controlling stake in Nevada Gold Mines and now calls most of the shots, largely making management decisions and setting the terms of employment.

Right before Christmas, roughly six months after the two companies formally merged their Nevada operations, one of Carney’s Newmont bosses told him he had to sign a new employment agreement with Nevada Gold Mines. His “new job” offered new rules, different benefits—and effectively no more union. The date of his firing and rehiring, he said, was just before the holidays. “It was a total surprise,” he recalled. “Unexpected.”

After the companies combined their Nevada operations, Carney became an at-will employee, suddenly vulnerable to being terminated for any reason. In a subsequent court filing that accused Nevada Gold Mines of failing to recognize the union, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), the federal agency that enforces labor law, noted that the new company’s actions “left many employees feeling terrified and betrayed.”

The consequences of Barrick and Newmont’s deal rippled through the mines, the local economy that depends on them, and the Western Shoshone, Paiute and Goshute tribes, whose unceded ancestral homeland is where much of the mining takes place. In Nevada, the fates of many people and communities are entangled with the gold industry. The merger meant that one megacompany was in charge, running what Barrick boasts is the world’s largest gold-mining complex.

Carney left the company in April of last year, a few months before his planned retirement. When he spoke to us in the fall of 2021, he had moved hundreds of miles away, to Pahrump, Nevada, a Mojave Desert community not far from Las Vegas. By the time he retired, he had worked for Newmont for about 28 years, an experience he said he “enjoyed tremendously.” He spent nearly a year and a half with Nevada Gold Mines; he said the company culture played a major role in his decision to leave mining earlier than he would have liked.

Carney wasn’t the only one who felt defeated. One former employee who worked in Nevada mining for about a decade, speaking on condition of anonymity, said things got so bad after the merger that he resigned, frustrated by what he believed was a “toxic” culture. He felt Nevada Gold Mines erased all boundaries between its employees’ work and personal lives, viewing them simply as “disposable assets.”

Because of the company’s size and influence, he added, Elko “is most certainly a company town.”

“Barrick owns Elko,” he said. “Pure and simple.”

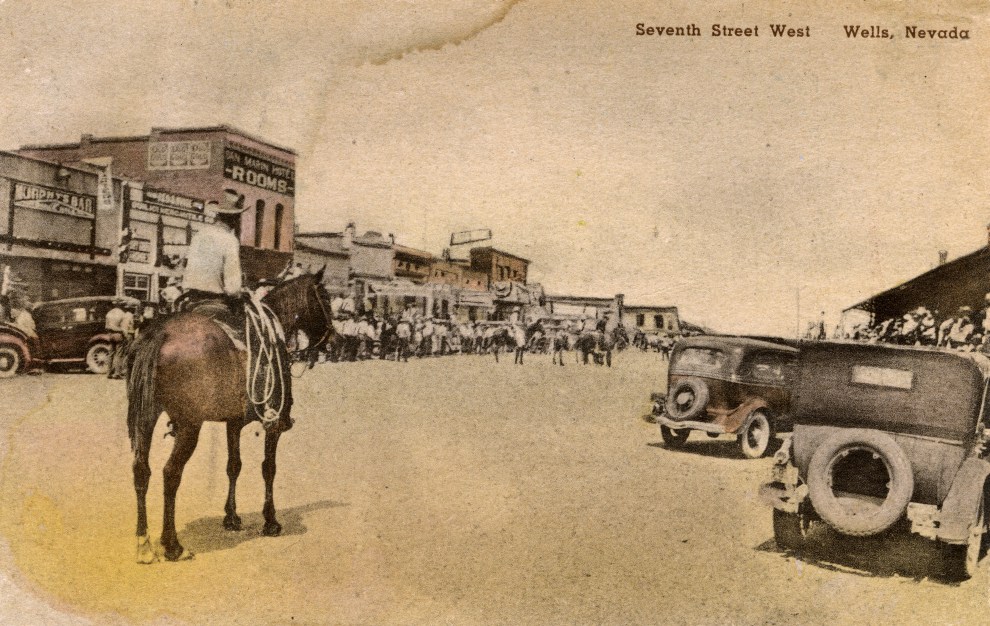

Elko County, Nevada, circa 1930.

Mary Evans via Zuma Press

On March 11, 2019, after decades of fierce competition in the Nevada goldfields, Barrick and Newmont announced some unlikely news: They would form a jointly owned company that would soon be named Nevada Gold Mines. Barrick—and its president and CEO, Mark Bristow—would take the helm. Months earlier, Barrick had merged with Bristow’s Randgold Resources, a multinational mining company with an aggressive reputation. By the time Barrick moved on Newmont’s Nevada mines, Bristow, a South African geologist and big game hunter known for his blunt rhetoric, was leading Barrick and calling the shots. Executives believed that merging the two operations would make their Nevada mines more efficient, increasing value for their investors. (The year of the merger, Bristow took home $17.4 million in compensation.)

In 2020, according to its financial filings, Nevada Gold Mines took in about $3.8 billion in revenue. Jewelry still drives a great deal of the demand for gold, but it is also an important investment vehicle. The company employs more than 7,000 people—the vast majority of mining workers in the area. Two smaller, nearby Elko-area operations, the Bald Mountain and the Jerritt Canyon mines, together employed more than 600 people, according to federal mine labor data.

In reporting this story, The Nevada Independent and High Country News spoke to more than 40 current and former employees, mining contractors, local residents and industry experts. Some described Nevada Gold Mines as, effectively, a monopoly: a company that had grown so large, its regional influence so vast, that local institutions—from the workforce and the union to the sovereign Indigenous nations and the rest of northern Nevada—were left with little power to negotiate on their own terms. In 2020, according to state data, Nevada Gold Mines accounted for about 75 percent of Nevada’s gold production, most of it sold beyond state boundaries in global markets. And the company is still growing: Nevada Gold Mines is exploring several new prospects and actively pursuing a permit for the Goldrush project, an expansion of its Cortez Hills Mine.

In its most recent state tax filing, Nevada Gold Mines was the second-largest taxpayer in the state, behind only MGM Resorts, the Las Vegas Strip’s largest casino operator, and a top taxpayer in four rural counties, including Elko County. The company manages more than 2 million acres of ranchland, and it is one of Nevada’s largest landowners. In Eureka County, where the Carlin Trend mines operate, it controls about 60 percent of all private land, according to an analysis of county records. These landholdings are often tied to valuable groundwater rights: In Crescent Valley, near the Cortez mine, Nevada Gold Mines holds 86 percent of all the basin’s water rights allocated to mining and ranching operations, according to one analysis by researchers at the University of Nevada, Reno. It buys equipment, parts and services from local businesses. To help power its mines, it operates a natural gas plant outside Reno and a coal plant, which the company says will soon become a natural gas plant and solar field, near the small town of Carlin.

“In the past, you’d sit back and watch these two big guys beat each other up over employees, over contractors, over water stuff,” said Glenn Miller, a natural resource and environmental science professor emeritus at the University of Nevada, Reno. “And now there’s just one giant company that doesn’t have a lot of competition for jobs and talent or for contractors and businesses.”

Before Barrick and Newmont merged, workers at all levels of the Nevada gold-mining industry would shift between two major companies. Now, since the creation of Nevada Gold Mines, that choice is gone, and many current and former employees claim the workplace culture has changed for the worse. Company executives have spoken publicly of their desire for a younger workforce, and the company has been hit with several discrimination complaints. Employee turnover has increased.

Greg Walker, the executive managing director of Nevada Gold Mines, acknowledged some workforce dissatisfaction. Walker is an industry lifer from Australia whose mining career has taken him all over the world. He helped run Barrick mines in Tanzania and Papua New Guinea, and he was an executive at the Pueblo Viejo gold mine in the Dominican Republic, one of the largest in the world.

Barrick executives say their new joint venture is not a monopoly. They also say that having one entity, rather than two distinct companies, allows them to spend more money on community programs in northern Nevada. In 2020, Nevada Gold Mines contributed $8.4 million in social investments. “As a single company, as Barrick or Newmont, we wouldn’t have supported these projects in the same way,’’ Walker said.

Catherine Raw, the chief operating officer of Barrick’s North American operations, noted that the global gold market is diffuse, disorganized, and China is the top producer. “Just because geologically we are now the biggest player in the Carlin Trend, it doesn’t mean we monopolize any one of those supply sources,” she said. “We’re not the only employer around, we’re not the only industry, we’re not the only customer.”

Even the residents who don’t work in mining are feeling the fallout from the merger. A Barrick executive has said the company’s activities employ about 4,000 contractors, who employ thousands of the more than 30,000 people who live in Elko and neighboring communities. In some cases, Nevada Gold Mines renegotiated deals with existing contractors, leaving some without the business they had once depended on. (Walker acknowledged that Nevada Gold Mines does “negotiate hard” when its contracts expire.) A new company also meant that retirees and their family members could receive different health care and benefits.

Inside a Barrick mine in Nevada.

Barrick Gold Corporation via Zuma Press

At times, the company seemed to resemble a shadow government, especially when it comes to providing what are generally considered public services—funding $5 million in loans for struggling local businesses during the pandemic, for example, about $30 million for broadband expansions in the Elko area, and more than $200,000 for employment programs aimed at Native American teens. In April, Nevada Gold Mines announced funding to help purchase a use-of-force simulator for the local police department. It has also partnered with a health-care company to help operate the Golden Health Family Medical Center, two private medical facilities where injured mine workers are often treated. In the spring of 2020, the company gave its employees $150 in “chamber checks” to spend at local stores. Industry executives refer to these sorts of contributions as part of maintaining a “social license to operate.” Altogether, its contributions make up a tiny fraction of its revenue.

Mining may not be northeastern Nevada’s only industry, but it’s at the center of daily life in Elko. Each morning before sunrise, coach buses fill with miners at parking lots around town. All day long, seven days a week, the buses run, dropping off workers at the end of their shifts and waiting to pick up the next group. Around the city, pickup trucks fly safety flags that identify work trucks. At the Goldstrike Mine, one of the area’s largest, even the biggest machinery looks tiny in the 1,200-foot-deep open pit. On the outskirts of town, mine suppliers, construction firms and equipment dealerships line the roads. Back in town, a motel sign announces “Miners and drillers welcome.” Even the bars evoke mining; in Elko, you can drink at the Silver Dollar Club or Goldie’s.

The company reinforces its hold through political lobbying. Nevada Gold Mines makes its donations across party lines and across the state, including in Las Vegas, the hub of Nevada’s economic power. In September 2020, as state lawmakers were weighing a tax increase on the industry, the state’s Department of Education issued a press release touting the company’s $2.2 million investment in online learning. That same year, the company gave $500,000 to a political action committee focused on Democratic interests. It also gave $750,000 to the Republican-aligned American Exceptionalism Institute, a 501(c)(4), known as a dark money fund, according to Newmont disclosure documents. Further hedging its bets, it donated $500,000 to the Stronger Nevada PAC, a campaign fundraising group led by former Lt. Gov. Mark Hutchison, a Republican.

Politicians of both parties help protect the industry’s interests. Adam Laxalt, a Republican running against Nevada Democratic Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto in the state’s 2022 Senate election, claimed in a recent op-ed published in the Elko Daily Free Press that Cortez Masto has “put radical environmentalists ahead of the miners.” Not to be outdone, Cortez Masto broke with factions of her party in October; the Senate committee she serves on extended an invitation to a Barrick executive to weigh in on proposed mining royalties, a policy long supported by Democrats. Soon after that, she earned a front-page headline in the same newspaper: “Cortez Masto: No Royalties.”

The consolidation of Barrick’s and Newmont’s Nevada operations reduced local competition for labor, allowing Nevada Gold Mines to allegedly start treating its workers with a degree of impunity, according to the current and former employees interviewed for this story.

Michelle, a former employee whose name has been changed to protect her identity, shared her story over multiple interviews with The Nevada Independent and High Country News. Michelle came to Newmont several years ago, amid what she was told was a push to bring more women into the industry. According to data published by The Wall Street Journal, Newmont’s percentage of female employees rose from nearly 11 percent of the workforce in 2013 to more than 15 percent in 2018, but dropped several percentage points just two years later. Meanwhile, Barrick too lagged behind; in 2013, its share of female employees was about 11 percent, and it has since fallen to 10 percent.

Mining jobs are coveted in Elko, but they can be dangerous and grueling: The shifts are long, often 12 hours, and the workdays can be even longer—almost 15 hours, if you include the commute. Workers often switch between day and night shifts. At night, industrial mine fields are illuminated by glaring lights from shovels, drills and truck cabs. Break times are closely monitored, and one false move, one small error, can lead to serious injuries. Hiring, Michelle said, was often done by attrition, and workers were weeded out quickly. “It’s either a do-or-die kind of thing,” she said. “You’re either going to make it or you’re not.”

Michelle was confident that she would succeed in this male-dominated industry. She was no stranger to the mines; some close family members worked in mining. And for many years, she enjoyed the work. Yet once Nevada Gold Mines formed, she said, a tough job got even tougher.

Mine managers, Michelle said, had always emphasized productivity; she recalled a time before the merger when a manager timed her group’s bathroom break. But she said the obsession with production only increased once Nevada Gold Mines took over. “That’s always been an issue,” she said, “and it’s worse now.” Another female employee said she was encouraged to save time by peeing off the side of her truck. A second female employee told us she urinated behind a truck because her efficiency rates were tracked, and she often felt an unspoken pressure to forgo bathroom breaks. Too many breaks cut into an employee’s productivity, which the company monitors closely. (“We work to ensure everyone’s rights are respected and voices are heard,” Nevada Gold Mines commented.)

Michelle said that the culture at her mine seemed to change, and morale quickly worsened. Management at the mine shuffled around, and she thought the rules were applied inconsistently. COVID-19 brought workplace issues to the fore, and Michelle noticed that many co-workers, even a manager, ignored protective requirements to wear masks or make other accommodations. The sexual harassment she witnessed—and experienced—on top of the COVID-19 issues, got so bad that she feared going to work. She reported her concerns, only to feel rebuffed.

“We think equality exists, until we’re in a position where it doesn’t,” she said.

There are at least six active federal court cases against Barrick or Nevada Gold Mines. The allegations include discrimination, unlawful dismissal based on age, and disability claims stemming from workplace injuries. (A number of claims pertain to incidents that occurred under Barrick management before Nevada Gold Mines was formed.) In addition, workers have submitted complaints to the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. In 2021, Walker told analysts that an internal culture survey of employees found “a lot of gaps in what we need to do.” The company declined to release the full survey results. COVID-19 has also put a strain on workforce retention and morale. As of November, only about 32 percent of employees were partially or fully vaccinated.

In an interview with The Nevada Independent and High Country News, Walker disclosed that the company’s turnover rates had about doubled, even though mining jobs tend to have the highest salaries in rural Nevada. (In a US Senate committee hearing, a Barrick executive stated that the average annual salary for Nevada Gold Mines’ employees was $94,000, which he claimed was the highest average industry wage in the state.) In mid-September, he said, the company had 500 vacancies, compared to an average of a few hundred.

Current and former workers interviewed for this story said there had been an increased rate of retirements, resignations, and terminations over the past two years, especially among older workers. “I feel that my job is now very much at stake,” one employee testified to the federal labor agency. “There have been a lot of rumors. A memo was even sent out by (the company) saying they want a younger workforce.” (During the fact check of this story, Nevada Gold Mines did not acknowledge the existence of such a memo.)

Company executives have also spoken openly about modernizing more parts of the company. In one presentation, the company said that its “focus in 2020 is to build some depth in the structure by bringing in younger talent.” In an interview with the Elko Daily Free Press, CEO Mark Bristow called gold mining an “aging industry” that needs more young people.

“We don’t have the luxury to pick and choose,” said Raw, Barrick’s chief operating officer, noting the high turnover rate. “Our focus is on attracting talent—the best talent.”

For Fred Coleman, concerns about age discrimination began before Nevada Gold Mines formed. Now 78, Coleman worked in the mining industry for almost 30 years. These days, he spends much of his time at home, working on landscaping and small construction projects with his wife, Lawona. On a warm afternoon in August, Coleman, wearing a baseball cap with a Navy logo above an expressive face, gave us a tour of their yard, with its newly built stone wall and a chicken coop. Standing in front of the house he’d purchased partly with the money he earned in the mines, Coleman admitted that he was on the older side for a mine worker. But he said that he was still fit enough to do the work, and his handshake remains powerful. He joked that he could beat us in arm-wrestling.

Coleman said his first experience with age discrimination came when he worked for Barrick. In the spring of 2018, he recalled, a co-worker told him that the rest of her crew was taking bets on his age. She figured she’d win by going to the source. Coleman was offended, but by that point, comments about his age had become common. “It was two years of, ‘When are you going to retire? Why don’t you retire?’” Coleman said.

At the Goldstrike Mine, Coleman drove a haul truck, effectively a 350-ton house on wheels. He was proud of his ability to operate some of the largest mining machinery on the planet. But after Barrick merged with Randgold and Bristow took over as CEO, Coleman believed there was a noticeable change in how supervisors treated older workers like him. Supervisors joked about his age to his face and told him it was time to retire. A member of Coleman’s crew, who spoke on condition of anonymity, recalled mocking his age, joking about writing him up for safety violations and saying things like “we don’t need him here no more, he needs to retire.”

Coleman was terminated a month after Nevada Gold Mines was launched. In 2020, he filed a lawsuit against Barrick for age discrimination. The company has denied the allegations. In a court filing, Barrick’s attorneys said his claims were “frivolously pursued” and that his termination was not discriminatory. Coleman’s lawsuit lists at least five other workers over the age of 40 who allege they were fired or say they were pushed out around the same time. (The lawsuit is still ongoing.)

Walker acknowledged that “there are a number of people that feel as though they’ve been discriminated (against),” and he said “those issues should be resolved in the proper channels.”

In other parts of the country where mining is ubiquitous, unions have a large presence. But not in northeastern Nevada: As of last year, Operating Engineers Local 3—the largest construction trades local in the country, which represents over 37,000 workers in California, Hawaii, Utah and Nevada—represented only about 1,300 employees in the area.

The relationship between Nevada Gold Mines and the union has been fraught since Barrick and Newmont combined their Nevada operations. In a May 2019 letter, Nevada Gold Mines had indicated that the union contract would remain in place. But according to employees in NLRB affidavits, the company seemed to reverse course in late 2019, around the same time Ches Carney noticed that union documents were disappearing. On one bulletin board, mine supervisors posted a note that read: “This bulletin board is for company-related materials only. All postings must be approved by the human resource department.” Over several months, as workers came forward with concerns, the National Labor Relations Board took the rare step of filing an injunction in federal court to compel the company to recognize the union.

Agents for the board interviewed numerous union workers and representatives as part of the lawsuit. What they found was troubling; the agency chided Nevada Gold Mines, saying its “illegal conduct threatens irreparable harm to national labor policy encouraging good-faith collective bargaining, the unit employees’ right to free choice, employee support for the union,” among other issues. In court documents, the company pushed back in strong terms, arguing that the agency’s “legal theories” were “factually and legally deficient.” Nevada Gold Mines argued that Newmont, not Nevada Gold Mines, signed the contract, and once the employment status changed, that agreement was no longer valid. When we interviewed Walker, he said the company initially wanted the union to hold an election with all Newmont and Barrick employees. But the union argued that even if management changed, its collective bargaining agreement would still be valid.

In August 2020, Nevada Gold Mines settled with the agency on behalf of The International Union of Operating Engineers Local 3 and said it would recognize the union. The union is actively organizing again, handing out flyers and information. Behind one employee parking lot, union leaders posted a sign framed by two American flags: “ALL NGM MINERS BE AT THE VFW AUG 11TH 5 PM – 8 PM Q&A ON BETTER MEDICAL A PENSION A VOICE A UNION!”

Still, the issues have continued, and, in early 2021, the federal labor agency sent a letter to Nevada Gold Mines with new charges from the union. They included allegations of changes to contracts, changes to the terms of employment, discharge and refusal to bargain in good faith.

Supporters of Operating Engineers Local 3 say the union is seen as the last line of defense against the company’s potential overreach and unfair terminations. Losing those job protections, one worker told the agency, “is going to be devastating to our community.”

Workers who have left or been terminated by Nevada Gold Mines can theoretically find work at a few smaller mines in the area. In a town where everyone talks, others fear that contractors and mine suppliers will not hire them if they leave Nevada Gold Mines on anything less than positive terms. Some workers alleged the company has, in certain cases, made it difficult for terminated workers to even step foot on Nevada Gold Mines property if they are working for a mine contractor. (Walker disputed this, saying that workers are not banned unless they were fired “for gross negligence or something malicious,” including for safety issues.) The federal labor board, in a 2020 complaint, echoed this: It wrote that Nevada Gold Mines “prohibited terminated employees from obtaining future employment with other employers and contractors by banning them from all mining and processing sites operated by (the company).”

Fred Coleman suspects that this is what happened to him. He was fired following an alleged safety violation, which Coleman disputes. Coleman, who has never worked for a unionized mine, said a union would have fought for him. “I would have had somewhere to go for recourse” with his discrimination complaint, he said. After leaving Barrick, Coleman interviewed for other mining industry jobs, but the opportunities evaporated, he said, once potential employers learned he had been terminated. (In a response to Coleman’s complaint, Barrick denied the allegation that he was “blackballed.”) This ignominious end to his mining career, the feeling of being brushed aside from a job that was a major part of his identity, still haunts him. In interviews, Coleman frequently mentioned that he was good at his job.

“I know I may be a little older—but I think I could have worked another three to five years, honestly, and done a really good job for them,” he said.

Nevada Gold Mines is already a very large operation, and it wants to get even bigger. Its expansion plans include a project known as Goldrush, what the company describes as a “world-class” deposit near the Cortez Mountains, which rise above the Crescent Valley, roughly 80 miles from Elko and more than an hour by bus for miners. Few people are as familiar with this area as Brian Mason, the vice chairman of the Shoshone-Paiute Tribes of the Duck Valley Indian Reservation.

Once a prominent Barrick employee, Mason is now a critic.

The journey from Elko to Cortez Hills is marked by generations of history for Mason and his family, a history that is now entangled with Nevada Gold Mines. As Mason drove with us to the mine in August, he passed the JD Ranch, a place that his grandmother had lived near for years, which is now owned by Nevada Gold Mines. His uncle worked at another ranch now owned by the company. The road leads to the base of Mount Tenabo, a sacred place for many Western Shoshone tribes, and its white cliffs, which long served as a beacon on trips to the Humboldt River.

If you squint from the side of the road, you can see underground tunnels leading to the Goldrush deposit. The fact that the federal government has already allowed Nevada Gold Mines to explore in this area, a significant cultural site, is unsettling to Mason. But the General Mining Law of 1872, a relic of the United States’ ruthless determination to settle the West, is permissive to companies seeking to develop mining claims.

Mason’s relationship with mining, and with Barrick in particular, is complex. For years, his job was to help Barrick improve its relationship with Indigenous communities—to forge compromises that allowed mining to continue on Western Shoshone land. Mason strongly believes that the company should pay and be held accountable if it wants to mine Western Shoshone territory. Mining in northern Nevada is a fact of life, unavoidable and omnipresent, and the tribes in northern Nevada, Mason argues, ought to be compensated.

“Mining companies get it,” Mason said on the drive. “But they’re not going to do something until they’re forced to do something, right? Because they’re businessmen. What we want is going to add to the all-in sustaining cost of that ounce of gold—not by much, but it will add some.”

Mason, a former Marine, often wears his long gray hair in a ponytail. He has a loud, gravelly voice, and, when animated, tends to curse in long inventive blue streaks. In 2011, he began to think about resigning from his job as an environmental supervisor at Barrick. Several years earlier, the company began offering collaborative agreements to Western Shoshone tribes, which had been protesting an expansion of the Cortez Hills Mine, but Mason felt that Barrick hadn’t followed through. When he put in his resignation, he got a call from a senior executive at Barrick North America. Mason told him why he was leaving. “I can’t work for a company that is not going to do what they tell the tribes they’re going to do,” he said.

Barrick asked if Mason would run a department that became known as Native American Affairs, something Mason believed the multinational company desperately needed.

Using those collaborative agreements, Mason worked to smooth tensions between tribal governments and Barrick. He advocated for Western Shoshone companies to get contracts for water truck deliveries, construction and other services. He helped recruit tribal members for jobs and funneled mining dollars to tribal governments. The division, under his leadership, won social responsibility awards and political praise. “It’s a business decision to collaborate and include an Indigenous group,” he said.

After Bristow took charge at Barrick, Mason said he began to observe a “cultural change” in the company. Barrick, Mason claimed, slashed his several million-dollar budget by more than half and appeared to prioritize the bottom line above all else. Around the time Nevada Gold Mines was formed, Mason left the company. Mason suspected that the corporate relationship with the tribes would deteriorate: He said he has watched it happen as the vice chairman of the Shoshone-Paiute Tribes of the Duck Valley Indian Reservation. Instead of a company willing to meet a high standard to mine gold on Western Shoshone land, he sees one hoping to skate by with the minimum.

In 2020, Nevada Gold Mines wanted tribes to sign an updated version of a collaborative agreement, but the request was met with skepticism. In November 2020, Mason helped write a rebuttal letter to the company, explaining point by point why it was not meeting the existing commitments laid out in the collaborative agreement, which several tribes have since signed.

Multiple tribes, the letter said, “do not agree with this collaborative agreement document, especially with the lack of performance of the last year-and-a-half of its social obligation to hire tribal members, the utilization of tribally owned businesses, the sharing of benefits or other items.”

Mason believes that Nevada tribes are far from justly compensated for the extraction that takes place on their ancestral homelands, and many remain cut off from the mining revenue that circulates through northern Nevada. Calling into the state Legislature in May, Mason said that Nevada tribes should receive a portion of mining taxes, which currently go only to state and county governments. But the idea, Mason said, did not gain traction in Carson City, where the company, the governor’s office and lawmakers negotiated a tax deal behind the scenes. “We were never brought to the table,” he said. Mason hopes to continue raising the issue with state legislators and remains determined to seek company buy-in.

Like many of Nevada Gold Mines’ operations, the Goldrush project will take place on land that Western Shoshone tribes claim. The Treaty of Ruby Valley, signed in 1863, provided for the right of safe passage, but it did not hand over ownership. The Western Shoshone have maintained a claim to the land, but the U.S. legal system has not been hospitable to their claims. In 1985, the Supreme Court weighed in on a case involving the Western Shoshone sisters Carrie and Mary Dann—two prominent activists for tribal rights who ranched in Crescent Valley. The court ruled against them, supporting a lower court decision that found the right to the land “extinguished” after the U.S. deposited $26 million in damages into a Treasury account. After a law was signed by President George W. Bush in 2004, some tribal members accepted a distribution of the settlement funds, but the U.S. government did little to recognize their land claims under the treaty. In 2006, the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination chastised the U.S. over its treatment of the Western Shoshone.

Carrie Dann opposed Barrick’s Cortez expansion in 2008, fearing that it would suck water from Mount Tenabo. In a move that showed the company’s far-reaching influence and power, Nevada Gold Mines purchased the Dann Ranch in 2019, and in 2020, it received permission from the state to use water from the ranch as part of its mining operations at Cortez Hills. For mining companies, buying up ranches is often a way to exert control in an area. Through significant land holdings, companies can effectively create buffers around their operations that shelter them from complaints from local ranchers, including over water use.

Alissa Wood, who leads the company’s communities and corporate affairs division, said that Nevada Gold Mines respects the tribes’ decision not to sign the new agreements and will honor existing collaborative deals. She said the multibillion-dollar company plans to continue fulfilling its commitments. In 2019, it pledged nearly $14 million over a decade to a scholarship fund for Western Shoshone high school students. The company also broadened its agreements to include the Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation and the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribe.

But the narrative the company tells about itself in public is different from the way it operates on the ground, according to Alice Tybo, the vice chairperson of the South Fork Band of the Te-Moak Tribe of Western Shoshone. Tybo, a former employee of the Elko County School District, used to work with Barrick at quarterly dialogue meetings. Those meetings, Tybo said, changed when Nevada Gold Mines took over. There’s more pageantry now, she said, with tribal flags displayed prominently, but less substance. Tybo no longer bothers to attend meetings, saying the flags create “an illusion of participation.” “It used to mean something,” she said. “It doesn’t mean anything anymore.”

In this part of rural Nevada, often forgotten by the rest of the state, money is often short, and Nevada Gold Mines—as well as Barrick before it—have helped fill the gap. The company provides aid to elders, energy assistance and resources for youth programs. In 2020, it donated about $400,000 in COVID-19 relief funding to Native communities.

“What’s the problem?” asked Davis Gonzales, former chairman of the Elko Band of the Te-Moak Tribe of Western Shoshone. Gonzales signed the updated collaborative agreement, which he described as similar to past agreements. In an October phone interview, before he left office, he listed the benefits in the agreement, citing language that spoke of fostering mutual understanding and respect. “If it wasn’t for Nevada Gold, we wouldn’t be where we’re at,” he said. “They’re willing to help us.”

On a warm August day, Mason parked his car near a plaque commemorating the Western Shoshone and looked up at the white cliffs lining the side of Mount Tenabo. From this spot, the crest of the Cortez Hills pit was visible. It felt strange to be back here as a critic of Nevada Gold Mines, he said, after working for Barrick for so long.

At the center of the altered landscape, not far from humming mine trucks and the underground tunnels leading into the Goldrush deposit, he said: “I just wish they’d be better neighbors.”