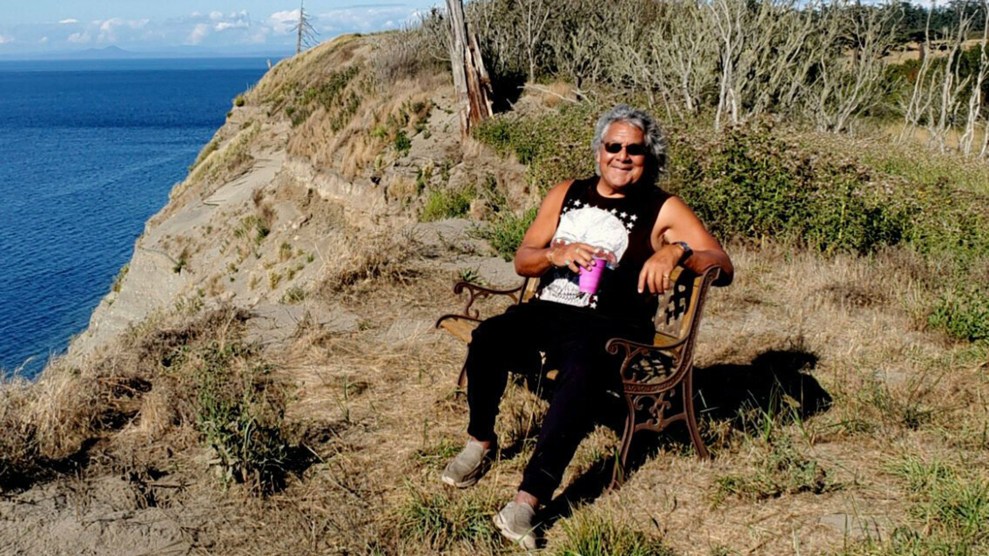

Marty Bluewater never expected to be the only human being living in a 400-acre wildlife haven. Courtesy Marty Bluewater

This story was originally published by Atlas Obscura and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

On Washington State’s Protection Island, Marty Bluewater stands alone. A colony of gulls swoop and squawk around the sandy bluffs where he looks out to the sea, watching tufted puffins bob in the water in search of fish to feed their young. His morning music is the sound of waves crashing onto the beach below, where harbor seals stretch out under the sun. Bluewater is the only human resident of the roughly 400-acre island, which became a wildlife refuge in the 1980s. He says living here has been nothing short of a dream: “It’s unique in all the world.”

Now off-limits to the public, Protection Island is home to wildlife and Bluewater, who’s been granted lifetime use. He bought his piece of the island in the early 1970s, and almost 50 years later, the modest wooden cabin he built as a getaway is now more or less home. Every three or four days, he makes trips by boat into Port Townsend, a few miles away, at the mouth of Puget Sound. There he stocks up on necessities such as bottled drinking water and food. The supply runs are all part of the adventure. “On my way over the other day, two orcas swam around my boat,” says Bluewater.

He loves the island’s unpredictable thrills, and built his cabin with full windows facing the sea. “Great in storms,” he says. “One time a 70-plus mph wind blew out one of my windows. I quickly had to get a hammer and nails and a big sheet of plywood to seal up the opening before the wind destroyed a bunch of stuff,” he adds with cheerful nonchalance.

The roughly triangular island, just off the Olympic Peninsula, had served as farmland and, during WWII, was used for artillery target practice. In the 1960s, investors bought it for $275,000 and marketed 800 subdivided lots to families and retirees as a place where they could build vacation cabins.

Yet there was a problem. The island provided breeding grounds for several species, including harbor seals and rhinoceros auklets: thickset seabirds with a distinctive spike on their bills. Protection Island is also the Salish Sea’s largest nesting area for glaucous-winged gulls. In the early 1970s, artist and wildlife biologist Zella Schultz, who had studied the gull colony, and Audubon Society member Eleanor Stopps raised concerns that increased human activity would interfere with the island’s thousands of nesting birds. The National Audubon Society, Nature Conservancy, and other groups soon rallied to the women’s call to see the island protected.

After Shultz’s death in 1974, the Nature Conservancy bought 48 acres of the island and resold it to Washington State, creating the Zella M. Schultz Seabird Sanctuary. Stopps wanted to make the entire island a protected wildlife refuge, however, and started buying lots in the late ‘70s.

“Eleanor started a program where for a small amount of money, people could adopt a seabird, and then she was going to put that money towards buying lots on Protection Island before they could be developed,” says Lorna Smith of her late friend, who died in 2012. Smith, who currently serves on Washington’s Fish and Wildlife Commission, helped Stopp’s campaign gain momentum. “We tried going through the Fish and Wildlife Service, but they didn’t want to take over Protection Island. It wasn’t a priority for them. So, we decided to go the legislative path.”

The women instigated a massive campaign that eventually went national. Supporters sent thousands of letters to members of Congress in hopes of convincing them to pass the Protection Island Wildlife Bill.

Bluewater, along with others who owned property on Protection Island at the time, wasn’t about to forfeit his land. In a statement during the legislative debate over the island’s fate, Bluewater made his case: “With regard to the future of the Island, I have two major concerns. First, that the Island always remain the special place that it now is and secondly, that my rights as a property owner are not lost. I believe that both of these things are possible. To me, nothing is more important than preserving the land, the sea, and the wildlife that grows from it.”

Even though the promised vacation paradise never fully materialized—Protection Island had a small airstrip but was still without electricity, potable water, and other amenities—landowners like Bluewater didn’t want to lose what they had. Without access to basic needs, however, only a handful of cabins were ever built.

“I think they had bigger plans for the place than it could really sustain,” said Bluewater. “It was probably a little bit of a harebrained scheme to begin with. It was a good idea, but it’s just better that it worked out the way it did.”

Meanwhile, conservationists were able to line up congressional support and, in 1982, lawmakers signed the Protection Island Wildlife Bill, designating the island as a National Wildlife Refuge.

“We felt like our rights were being taken away,” says Linda Odegard of the bill’s passage. In 1982, she and her husband had already built a cabin on the island, where they hoped to retire one day. “It was a very magical place. I remember one day I looked out and there an elephant seal, and we didn’t even know we had any in the area…Things like that just made it so special.”

Like Odegard, Bluewater had also grown attached to his island home. “It was just meant to be a weekend place at first. But I fell in love with it and that’s when I started dreaming, well, maybe someday I could actually live there,” says Bluewater.

While many owners ended up selling their undeveloped lots to the government, those with cabins were given the option of continued use with some restrictions. They could only access the island by boat, for example, and some beaches would be off-limits during nesting season, from October to February.

“The few people that I remember talking to at the time who lived there were incredibly protective of the island. They loved it, and they didn’t want to see it developed into 800 homes,” says Dave Galvin, who was president of Seattle Audubon Society from 1980 to 1982. “We wanted the eventual settlement to be something where they could get their money back, basically, having bought these lots and then not being able to use them.”

Bluewater and Odegard were among the owners given the option of either lifetime use or for a fixed term. Odegard chose a term of 20 years. “I figured in 20 years I’d be 65 and wouldn’t want to go out there anymore,” she says. “Well, I was wrong about that. It’d be nice to still be able to visit.”

Only Bluewater took the lifetime offer. He never thought that, decades later, he’d be the only one still living there. “One of the reasons the other people didn’t take lifetime use is because they were being practical, knowing that they’d be too old someday to go over there. I just didn’t worry about that, you know. I’ll go there as long as I can crawl up the hill,” he says as birds screech in the distance. “Yet knowing that when I’m gone, it’s going to be just the protected refuge forever is as important as anything to me, too. That’s how much I appreciate how special this place is.”