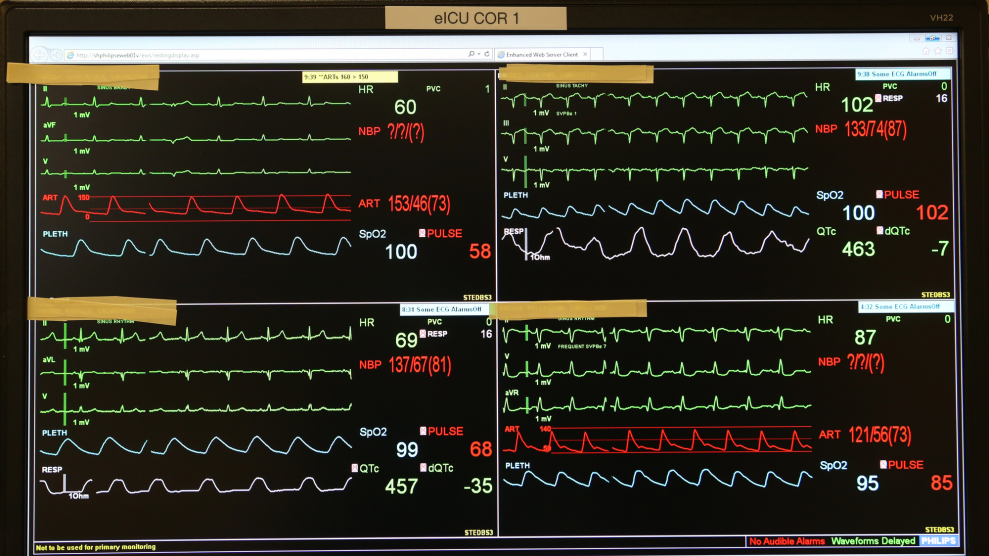

Patients’ vital signs on a monitor in Westwood, Massachusetts, on Tuesday.Angela Rowlings/Getty

This story was published in partnership with ProPublica, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for ProPublica’s Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox as soon as they are published.

Medical staffing companies—some of which are owned by some of the country’s richest investors and have been cutting pay for doctors on the front lines of the coronavirus pandemic—are seeking government bailout money.

Private equity firms have increasingly bought up doctors’ practices that contract with hospitals to staff emergency rooms and other departments. These staffing companies say the coronavirus pandemic is, counterintuitively, bad for business because most everyone who isn’t critically ill with COVID-19 is avoiding the ER. The companies have responded with pay cuts, reduced hours and furloughs for doctors.

Emergency room visits across the country have fallen roughly 30%, and the patients who are coming tend to be sicker and costlier to treat, the American College of Emergency Physicians said in an April 3 letter to Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar. The professional group asked the Trump administration to provide $3.6 billion of aid to emergency physician practices.

“Without immediate federal financial resources and support separate from what is provided to hospitals, fewer emergency physicians will be left to care for patients, a shortfall which will only be further exacerbated as they try to make preparations for the COVID-19 surge,” the organization said in the letter.

The American College of Emergency Physicians’ 38,000 members include employees of large staffing firms as well as academic medical centers and small doctor-owned practice groups. The letter was signed by the group’s president, William P. Jaquis, whose day job is as a senior vice president at Envision Healthcare, a top staffing firm owned by private equity giant KKR.

Envision, which has 27,000 clinicians, said it’s cutting doctors’ pay in areas that are seeing fewer patients, as well as delaying bonuses and profit-sharing, retirement contributions, raises and promotions. The company also cut senior executives’ salaries in half and will impose pay cuts or furloughs for nonclinical employees. However, Envision said that it’s adding doctors in hard-hit New York and other coronavirus hot spots.

“Where they lose their normal billing revenue, medical groups are losing money. Where medical groups are losing money, they have to reduce salaries and furlough workers,” Envision CEO Jim Rechtin said in a statement. “Unfortunately, we are no different.”

KKR didn’t respond to requests for comment. Co-founders Henry Kravis and George Roberts said they’ll donate $50 million to first responders and health workers, as well as forgoing bonuses and the rest of their salaries for the year, Forbes reported. Forbes estimates Kravis’ wealth at $5.6 billion and Roberts’ at $5.8 billion.

Before the pandemic, Envision made a lucrative business out of buying practice groups in specialties where patients don’t choose their provider, such as ER physicians and anesthesiologists, according to Dr. Marty Makary, a surgical oncologist at Johns Hopkins Medicine who studies health care costs. Envision could then charge patients high prices for out-of-network care, a practice known as “surprise billing.” The model was profitable until a public backlash led lawmakers to investigate the practice, according to Makary.

“Private equity consolidated large physician groups in an unprecedented financial gamble using capital and banking on revenue not skipping a beat,” Makary said. “When the investment model works, investors get rich. When the investment goes sour, who bears the risk? As in the mortgage crisis of 2008, taxpayers are bearing the risk of financial gambles of investors.”

Envision won’t send surprise bills to COVID-19 patients, the company said; patients will be responsible only for in-network copays.

Health insurance companies, which are often at odds with doctors and staffing companies over payment disputes, have said they support government aid to hospitals and doctors, but they specified that relief should go to “small and independent practices.” A lobbying group representing insurers and business groups raised concerns about the potential for investors to benefit from the emergency physicians’ request for $3.6 billion.

“We need to do everything to support health care workers on the frontlines of this pandemic, and we want to make sure they get the resources they need to care for patients and protect themselves,” the Coalition Against Surprise Medical Billing said in a statement to ProPublica. “At the same time, federal funds should not be used to bail out private equity firms during a public health emergency, especially when there are no federal surprise billing protections in place to protect consumers at their most vulnerable.”

The top lobbyist for the American College of Emergency Physicians, Laura Wooster, warned that efforts to single out companies with rich backers could catch patients in the crossfire. “If you start trying to parse big or small, independent or not, it’s going to get messy really quickly,” Wooster said in an interview. “This isn’t the time to figure out too late that unintended consequences left a rural emergency department understaffed because it happened to be staffed by one of the bigger groups.”

Wooster noted that it’s not only big private equity-backed staffing firms that are hurting, and she provided data from small practice groups that are also losing business and scaling back. She said she couldn’t commit to conditions on receiving aid—such as restricting “surprise billing,” investor payouts or executive bonuses—without seeing how the terms are structured. She said the administration hasn’t offered a proposal at that level of detail nor asked for one.

Katy Talento, a health adviser to President Donald Trump from 2017 to 2019, offered a different view. “If they’re private equity-owned, I have no sympathy, and I don’t think any patient out there struggling paycheck to paycheck—if they have a paycheck—is remotely interested in the crocodile tears of private equity firms and their revenue losses,” she said. “We have to target rescue funds to the hardest-hit areas, and emergency physicians are not the hardest-hit target of our charity.”

The administration hasn’t said much about how it plans to distribute a $100 billion fund for health care providers that was part of the $2 trillion coronavirus stimulus package. Last Friday, Azar said “a portion” of the money would reimburse hospitals for caring for uninsured patients. He said providers would get paid at Medicare rates and prohibited from billing patients beyond that.

Lawmakers have spent months working on legislation to address surprise billing, attempting to accommodate the interests of patients, doctors and insurers. Medical staffing companies including Envision launched attack ads against some proposals but agreed to a provider-friendly bill advanced by Sen. Bill Cassidy, R-La. (who is a gastroenterologist). A bipartisan compromise failed to make it into the December spending deal because of a turf war between congressional committees. Lawmakers briefly considered reviving the compromise as part of the coronavirus stimulus package but didn’t want to slow down getting relief into the economy quickly, according to congressional aides.

Medical staffing companies said they have benefited from tax relief and advance Medicare payments included in the stimulus package. Still, Envision and other private equity-backed staffing firms have swiftly responded to lost income by cutting pay and hours for doctors.

One Envision anesthesiologist in the mid-Atlantic region said his base salary was cut by 30% even as he’s being asked to intubate COVID-19 patients—a procedure that puts providers at high risk of exposure to the virus.

“My hope in any type of bailout going toward health care providers is it should go to them,” said the anesthesiologist, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of losing his job. “It should not be going toward rewarding executives or shareholder profits. Anybody actually coming in physical contact is taking all the risk, so that’s where the relief should be going.”