Tom Williams/Congressional Quarterly/Newscom, Zuma

David Bernhardt, the man in charge of the nation’s public lands, has come through the revolving door of Washington, D.C. lobbying and back out again. Before becoming secretary of the Department of the Interior, he collected nearly $5 million for his firm Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck as a lobbyist and lawyer from energy clients.

Since he took the new post in July 2017, Bernhardt’s former clients have spent a lot of money trying to influence the Department of Interior. Seventeen of them have coughed up a combined $29.9 million to lobby the Trump administration since January 2017, according to a new report from the consumer advocacy group Public Citizen. Of those, 14 lobbied the Department of the Interior. The top spenders include San Diego electric and gas utility Sempra Energy, Norway state-owned oil company Equinor, the oil and gas company Noble Energy, the lobby group Independent Petroleum Association of America, and the water and land development company Cadiz Inc.

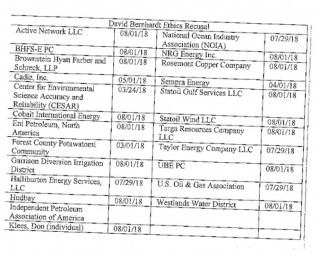

David Bernhardt’s notecard listing which former clients he couldn’t work with. The recusal period is over.

“Under Trump, insiders have taken control over virtually every agency, and the Interior Department is one of the far most egregious examples,” says Alan Zibel, research director of Public Citizen’s Corporate Presidency Project and the report’s author. “Under Bernhardt, the Interior Department appears to have priced access to our nation’s resources at $30 million and counting.”

Bernhardt’s former firm has seen its coffers grow 300 percent to $12 million from Interior-related revenue since Bernhardt joined the agency, which is notable—it saw much lower figures in the Obama administration.

Bernhardt’s predecessor, Ryan Zinke, drew widespread scrutiny, racking up federal investigations for questionable behavior. But Bernhardt, who worked at Interior under George W. Bush, hasn’t cultivated the same kind of attention.

“Zinke was more of a personality,” says Jayson O’Neill of Western Values Project, a group that has been tracking Interior rollbacks, but Bernhardt “hasn’t stopped undermining public lands protection and environment protection, and allowed the industry to run roughshod over our lands.”

On Bernhardt’s watch, Interior has sped up environmental reviews for new projects, rolled back oversight for offshore drilling enacted after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster, opened up millions in acres of protected land to oil and gas drilling, and weakened the Endangered Species Act.

As another example of Bernhardt’s industry-friendly approach to his job, Public Citizen points to Bernhardt’s former client Westlands Water District, which has lobbied to weaken endangered species protections to divert more water for agriculture. Westlands has spent more than $1.5 million lobbying Interior and Department of Justice since 2017.

From the report:

After starting work at the Interior Department, Bernhardt continued to take actions that benefited former clients. Bernhardt acknowledged in a New York Times interview that, months after joining the Interior Department in 2017, he directed a department official to weaken protections for fish in an effort to distribute more water to Westlands – the same issue on which he had previously lobbied. Bernhardt told the Times that “Everything I do, I go to our ethics officers first” and said that he was executing President Trump’s agenda of helping help rural America. “I don’t believe for a minute that I’m doing things to benefit Westlands. I’m doing things to benefit America.” Nevertheless, agency documents reveal that Bernhardt, as deputy secretary, held numerous meetings on California water issues as soon as a few weeks after he joined the agency, even though he was barred by ethics rules from working on those issues for a year. Documents released by Friends of the Earth, the environmental group, show extensive e-mail conversations between Bernhardt and an agency ethics official over recusals and other ethics issues.

In November 2019, the Interior Department released a proposal to award Westlands a permanent water supply contract that would siphon away water from Northern California rivers to San Joaquin Valley agribusiness, including growers of almonds, pistachios and other crops. That diversion of water will come at the expense of San Francisco Bay Area residents, who get fresh water from the same source, and conservation groups say it will harm fisheries and threaten vulnerable wildlife.

Rather than recuse himself from decisions that would affect his former clients, Bernhardt has played an active role in decisions like rolling back delta smelt protections under the Endangered Species Act, a decision that directly benefits Westlands.

And about that “ethics officer:” The Office of Government Ethics has a narrow interpretation of conflicts of interest. Early on, President Trump also issued an executive order that extended those rules to ban lobbying an agency five years after leaving the administration, but 33 officials have already violated it.

There’s no indication that the revolving door will stop turning any time soon. Just look at Trump’s administration, which is packed with staff who were recently associated with fossil fuel interests like Koch Industries, American Chemistry Council, the coal company Murray Energy, and Dow Chemical. “We’ve seen a pattern in practice across the Trump administration: Not only is there no enforcement of the ethics rules, but there is no accountability for the myriad lobbyists they’ve hired across our government,” O’Neill says.

Bernhardt used to carry around a notecard to remind himself of the two-dozen former energy clients he couldn’t work with at the Department of Interior, because he used to represent them as a lawyer or lobby on their behalf. Now, Bernhardt doesn’t even need the notecard—because all of the deadlines for those recusals have now lapsed.