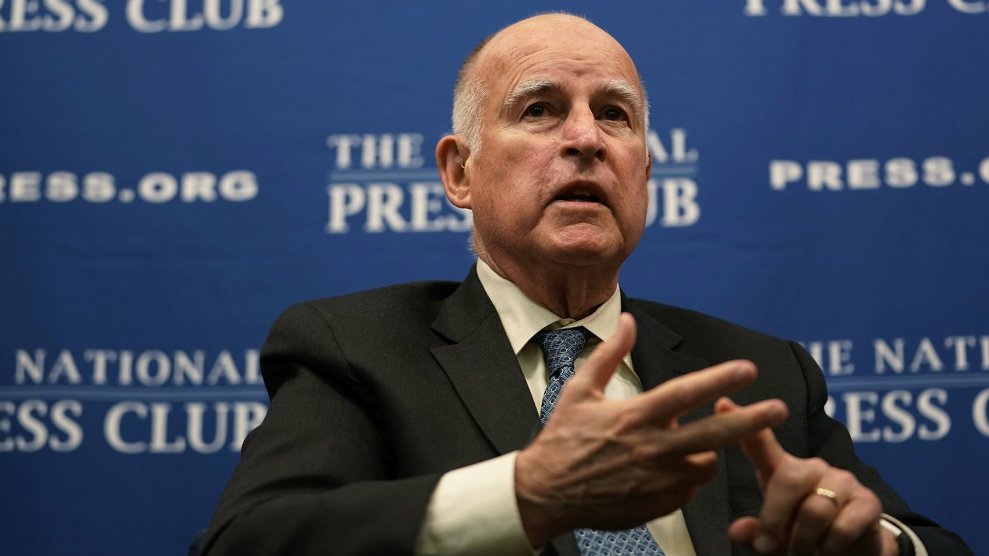

Alex Wong/Getty Images)

This story was originally published by Grist. It appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

A romance between California and China blossomed on stage Wednesday morning at the opening ceremony for a conference in San Francisco. California and China share a common adversary in President Donald Trump, giving them common purpose and strengthening the cross-Pacific bonds of affection. As the proverb says, the enemy of my enemy is my friend.

The ceremony kicked off the opening of the “China Pavilion,” the name for the Chinese-organized part of the Global Climate Action Summit initiated by California Governor Jerry Brown.

Chinese government officials in black suits smiled, shook hands with the Californian politicians, and pledged to work together with California to slash greenhouse gas emissions, while Brown exhorted them to treat that climate change as an existential threat. But Brown delivered that message in a jocular way.

“We are going to hell very quickly, very quickly,” he said. “It isn’t certain we are going to avoid that awful outcome, so don’t feel too comfortable even as you drink your California wine and get a little tipsy, I hope. Never forget, we are on the road to perdition. I don’t know how they say that in Chinese, but it’s not good.”

The fact that the room was packed with Chinese officials “says volumes about the commitment of China to confronting climate change,” Brown said.

Representatives from California and China signed several memoranda of understanding, detailing plans to work together on fuel cells, zero emission vehicles, and such, but if you were hoping for China to announce it’s shutting down all its coal plants next year, well, nothing like that happened.

Instead, Xie Zhenhua, who has served as China’s climate negotiator at the United Nations, gave examples of the ways his country is trying to figure out how to lift people out of poverty without the aid of fossil fuels. It all added up to a banal, if honest, assurance: “We have been exploring our own way of green, low-carbon development,” he said.

The future of the world depends on China being able to pull it off, said Nicholas Stern, an expert on economic development and the economics of climate change. “It couldn’t be simpler. We need to find a new growth story.”

China’s Belt and Road Initiative—a bid to extend its economic aegis across Asia—would encompass roughly half the world’s population, potentially bringing them better lives as well as much bigger carbon footprints. “If that group of people have a growth path in the next 10 to 20 years that looks like China’s, we would be in trouble,” Stern said.

California’s path is easier since the state is already tremendously wealthy compared to much of the world. But its challenge is tougher than China’s in that every Californian is responsible for some 11 tons of emissions every year. The average Chinese citizen emits some seven tons, Brown noted. “It’s too damn much. But we’re worse! But we’re going to get better together, that’s the key point.”

Brown hopes to change that. On Monday, he signed a eye-popping executive order telling California to squeeze off all emissions by 2045. “We have no chance of getting there unless China invests hundreds of billions of dollars in all the technology that will be needed,” Brown told the audience in the China Pavilion.

The potential for Sino-Californian climate collaboration, trade, research, and investment has grown more interesting as Trump rolls back US commitments and slaps tariffs on Chinese products. There’s a clear connection for Trump between climate action and trade because he believes that, as he tweeted: “The concept of global warming was created by and for the Chinese in order to make US manufacturing non-competitive.”

For politicians with a better grasp of reality, Trump’s antagonism toward China, and toward climate-change policy, has created a natural opening. In 2017, Brown began courting China in an attempt to sideline Washington.

You can find plenty of contradictions in China’s attempts to balance its ambitions for growth and environmental sustainability. Its emissions tripled from 2000 to 2012, and the country is still building coal plants. At the same time, large-scale Chinese manufacturing has made renewable energy cheap, and China is building clean mass transit infrastructure on a scale that puts the United States to shame.

A short bus ride away from the meeting on the far northern edge of San Francisco is an exhibit that underscores the tensions inherent in China’s growth. “Coal and Ice” displays large photographs of melting glaciers, floods, and other effects of climate change, paired with photographs of coal miners from around the world, including rare images of Chinese workers looking downtrodden and tired. The exhibit had several showings in China, but in one case the government shut it down, along with an entire festival.*

Correction: An earlier version of this article suggested the Chinese government shut down a exhibition of Coal and Ice due to its content. It’s unclear why the government shut it down.