A thin strip of coral atolls separates the ocean from the lagoon in Majuro, Marshall Islands.Nicole Evatt/AP

On Christmas Eve 2008, the president of the Marshall Islands declared a state of emergency after seawater flooded the country’s biggest urban areas, displaced hundreds of islanders, destroyed dozens of homes, and contaminated freshwater reserves. But this wasn’t some freak storm or tsunami; it was a garden-variety, seasonal storm surge, coupled with high tides—and it marked the third time that month the country had been hit by a major flooding event.

“If the tide had been two feet higher, it would have been much worse,” said Deborah Manase, then the deputy director of the Office of Environmental Planning and Policy Coordination.

Nearly a decade later, Manase’s words sound foreboding. By some estimates, sea level is projected to rise at least that much by 2100, thanks to climate change, but now scientists are saying thousands of islands may become uninhabitable even sooner than that due to frequent flooding and, consequently, freshwater contamination. Specifically, most low-lying atoll islands (islands formed of coral) will lack potable water by 2050, according to a study published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances.

Those islands could include, according to the authors, the Caroline Islands, Cook Islands, Gilbert Islands, Line Islands, Society Islands, Spratly Islands, Maldives, Seychelles, and Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

“Historically, these islands would be over-washed every 20 to 30 years, due to a big North Pacific winter storm or the passage of a typhoon,” Curt Storlazzi, the lead author on the study and a research geologist with the US Geological Survey, tells Mother Jones. “However, what we started to see is, because sea level is rising, these events are now happening multiple times per decade.”

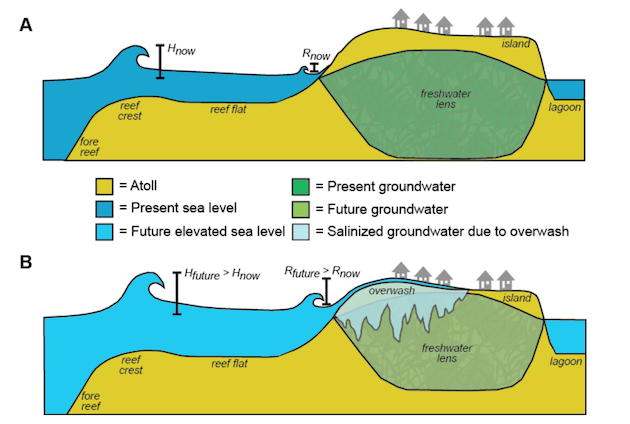

Current sea level versus future, elevated sea level (not to scale)

To get their projections, researchers from the USGS, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, International Atomic Energy Agency, and the University of Hawaii studied Roi-Namur, an atoll island in the Marshall Islands chain located in the central Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and the Philippines. Using the terrain measurements of Roi-Namur, they built computer models that could predict how sea-level rise would affect its freshwater resources and similar, low-lying islands.

Based on current greenhouse gas emission rates, sea-level rise will “lead to the annual wave-driven overwash of most atoll islands by the mid-21st century,” the authors write. This will cause “frequent damage to infrastructure” and the “inability of their freshwater aquifers to recover” between flooding events, leaving the islands without a clean water source.

“They are asking the right question,” says Bob Kopp, director of the Institute of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences at Rutgers University, who was not involved with this study. But Kopp said it’s worth noting some of the scenarios in the study showed “implausibly rapid rates of sea-level rise in the first half of the century.”

Still, Kopp doesn’t deny the threat is very real. “Based on the work they’ve done, it is likely that—even under an aggressive mitigation scenario—in the lifetime of children living on the Marshall Islands today, that [freshwater contamination] threshold is going to be crossed.”

For many island nations, expensive infrastructure projects, like desalination plants, aren’t an option, and residents will likely need to relocate, says Storlazzi. Globally, nearly 750,000 people live on atoll islands, he adds, which means the world could see an unprecedented mass of climate refugees fleeing their home islands in a few decades.

Without alternative options, experts say the safest bet is to simply prepare for the inevitable. “It’s a lot more cost-effective when you can plan for mitigation or relocation before a potential disaster rather than dealing with one,” says Storlazzi. “So that’s our ultimate goal: it’s really to save dollars and lives.”