Michael Isaac Stein/CityLab

This story was originally published by CityLab and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The only land route that connects Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana, to the rest of the continental United States is Island Road, a thin, four-mile stretch of pavement that lies inches above sea level and immediately drops off into open water on either side. Even on a calm day, salt water laps over the road’s tenuous boundaries and splashes the concrete.

The road wasn’t so exposed when it was built in 1956. Residents could walk through the thick marsh that surrounded the road to hunt and trap. But over the coming decades, the landscape transformed.

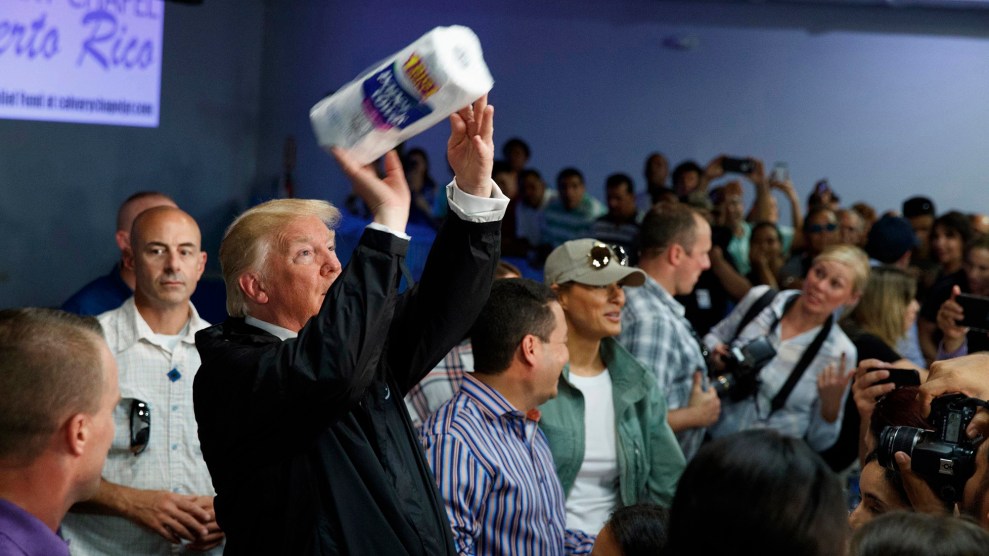

Island Road frequently floods, cutting off Isle de Jean Charles from the mainland.

Michael Isaac Stein

Levees stopped the natural flow of fresh water and sediment that reinforced the fragile marshes. Oil and gas companies dredged through the mud to lay pipelines and build canals, carving paths for saltwater to intrude and kill the freshwater vegetation that held the land together. The unstoppable, glacial momentum of sea-level rise has only made things worse. Today, almost nothing remains of what was very recently a vast expanse of bountiful marshes and swampland.

Isle de Jean Charles, home to the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw band of Native Americans, has lost 98 percent of its land since 1955. Its 99 remaining residents have been dubbed “America’s first climate refugees.”

“There’s just a little strip of it left,” said resident Rita Falgout. “There used to be a lot of trees; we didn’t have so much salt water.”

Like many of the houses on Isle de Jean Charles, her home is raised on 15-foot stilts to evade the increasingly omnipresent floodwaters. But the stilts can’t protect her from the island’s isolation. Strong winds alone can flood the road, cutting the island off from vital resources like hospitals. Soon the road will be impassable year-round.

“My husband is sick, and if we’re back here when the road floods, what are we going to do?” Falgout asked.

The only long-term solution is to leave.

Preparing for Tomorrow’s Climate Refugees

The residents of Isle de Jean Charles won’t be alone in their exodus. There will be up to 13 million climate refugees in the United States by the end of this century. Even if humanity were to stop all carbon emissions today, at least 414 towns, villages, and cities across the country would face relocation, according to a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. If the West Antarctic Ice Sheet collapses, researchers predict that the number will exceed 1,000.

And this isn’t a distant threat. At least 17 communities, most of which are Native American or Native Alaskan, are already in the process of climate-related relocations. Yet despite its inevitability, there is no official framework to handle this displacement. There is no U.S. government agency, process, or funding dedicated to confronting this impending humanitarian crisis.

Only one climate-related relocation is currently funded and administered by the government: the Isle de Jean Charles Resettlement Project.

This is a test run of sorts, a first-of-its-kind program that aims to create guiding principles for future resettlements. What makes the project unique is that it doesn’t just aim to resettle individuals. Its goal is to resettle the entire community together, as a whole, by constructing a brand-new town and filling it with the displaced occupants and culture of Isle de Jean Charles.

The project diverges from prior resettlements, which have largely followed a model of individual buyouts—offering lump-sum payments to residents and leaving them to their own devices to restart their lives. That model was used in Diamond, Louisiana, in the early 2000s.

Diamond, a historically black community situated in the heart of Cancer Alley, sat in the shadow of Shell petrochemical plants and for decades suffered through chemical leaks and explosions. Years of grassroots campaigning finally led to a buyout deal. One by one, the residents of Diamond took the money and left.

But even as the individual households found relief, the community shriveled away. Residents scattered, churches folded, and people fell out of touch. “The residents say they see each other at funerals and weddings, and that’s about it,” said Robert Verchick, the Board President of the Center for Progressive Reform, an environmental research nonprofit in Washington, D.C.

The death of Diamond highlights an important distinction. There is a difference between saving a community and saving its individual members.

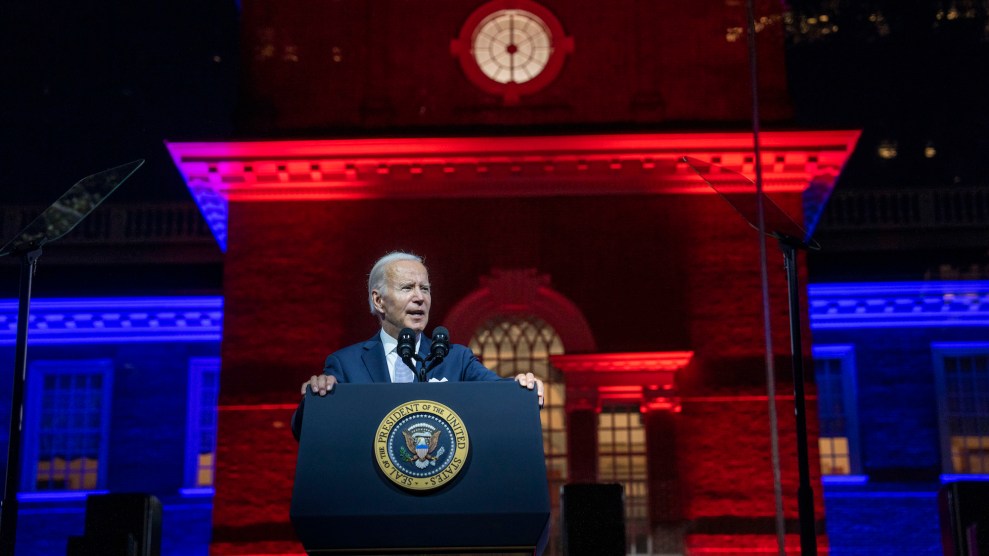

Chris Brunet, whose grandfather was tribal chief, sits in the shade under his elevated home.

Michael Isaac Stein

But for all its benefits, building an entirely new town for Isle de Jean Charles has high logistical hurdles, and with a price tag of over $48 million to move 99 people, it remains unclear whether this can serve as a replicable model.

The pace of resettlement has been sluggish, unable to match the urgency of the dilemma Isle de Jean Charles faces. Nearly two years after the project began, nothing’s been built. There is still no blueprint for the new town; the project’s administrators are just now narrowing down possible locations and entering contract negotiations with the engineering and architectural firm, CSRS, they hope will design it.

The problem, Verchick said, is that historically, the government is simply not good at resettling communities. Whether this deficiency is a product of inexperience or the sclerotic nature of bureaucracy is one of the things policy makers are trying to figure out.

But the central question is whether government-backed community resettlements will be feasible for the hundreds of communities that are approaching similar dissolutions.

“I think that’s a question that remains open,” said Mathew Sanders, who is running the project through the Louisiana Office of Community Development.

Isle de Jean Charles began contemplating relocation about 15 years ago, but with the lack of government guidance or structure, it was unclear where even to start. Then, during the summer of 2014, the Obama administration announced the National Disaster Resilience Competition (NDRC).

The competition, administered by HUD, had an ambitious purpose: to shift the way the U.S. manages natural disasters, from simply responding to and recovering from them, to planning and preparing for their inevitability. The competition would award $1 billion in funding to resilience projects across the nation.

The Louisiana Office of Community Development, Disaster Recovery Unit (OCD-DRU) worked with Isle de Jean Charles community leaders, NGOs, and development companies to draft an application for four resiliency projects, one of which was the Isle de Jean Charles Resettlement Project.

The application didn’t blunt the truth about the difficulty of the task at hand. It called the resettlement process “excessively complex.” It noted that failing to adhere to the preset timeline “could lead to potentially catastrophic outcomes.” It warned that a lack of prior examples to work from made the whole project uncertain. And it recalled that every government-backed relocation effort in the U.S. so far has been at least a partial failure.

Rather than balking at the hurdles, the OCD-DRU decided that Louisiana had an obligation to “improve upon our nation’s track record.” They would do this, the application said, by focusing not only on environmental resiliency, but “cultural resiliency” as well.

It was exactly what the competition was looking for, and the project was awarded the full $48.3 million it requested.

Taking the Time to Build Trust

That was more than two years ago. Since then, there’s not much to show for it: no land acquisition, no buildings, no precise plan. They are admittedly behind schedule.

But the OCD-DRU has been far from idle. While it hasn’t constructed homes, it has built something that will determine the success of the entire process: trust. This has meant overcoming decades of distrust between the island’s indigenous residents and the government.

“Everyone thinks giving away money is easy,” said Pat Forbes, the executive director of the Louisiana Office of Community Development. “But they’ve had experiences before that have led them to be wary.”

Isle de Jean Charles was, in fact, created as a result of a government-mandated relocation, albeit of a very different nature. It was during the violent Indian Removal Act era, when Native Americans were being murdered and driven off any land that could be used for agriculture.

Native people were forced to flee deep into the southern marshes of Louisiana to avoid the colonial persecution, into what was then designated as “uninhabitable swampland.” Now they are being asked to ignore decades of learned apprehension and trust the U.S. government to move them once again.

The fact that the confidence-building has taken years isn’t seen as a failure by those at OCD-DRU, but rather as an important lesson for future relocations of indigenous communities: It’s going to take time and patience. “There’s no shortcut to building trust,” said Sanders. “It really comes with time and effort and our ability to articulate progress.”

Unfortunately, this lesson will be applicable for many future relocations. According to a recent study by the Center for Progressive Reform, a startling proportion of communities attempting relocation are Native American or Native Alaskan.

“When we started looking at this, we were surprised that all of the communities we identified were tribal,” said Verchick. “It’s not a coincidence. Native people have rarely been able to choose the location in which they’re currently living.”

Even after two years, mistrust continues to play a role in some aspects of the resettlement process. It is crucially important among residents, for example, that they retain ownership of, or at least have unimpeded access to, the island once they have relocated. And many remain suspicious of what will happen if they voluntarily leave. Project leaders at OCD-DRU have guaranteed future access to the island. They are working on a contract to formalize that promise. Still, decades of prudent skepticism linger.

“We learned a long time ago not to trust when they come with paper and pen,” Falgout said.

Where Will the New Town Be?

Then there are the logistical obstacles.

The location of the soon-to-be town is also largely a question of economics. Small, rural towns all over the U.S. are dying for a myriad of reasons other than environmental inundation. The project planners want to keep residents as close as possible to their former lives, but they also have to avoid spending $48 million to save a town from environmental hazards only to have it fold because of economic ones.

Are there enough jobs near the site of the new town? Do those jobs match the skills and career experience of Isle de Jean Charles residents? Are there hospitals and grocery stores close enough to service the community?

Many Isle de Jean Charles residents make a living fishing, which limits how far away from the water they can move. Too far north and you’ll keep the town dry but create an unemployment crisis.

The location also has to be one that can attract new people over time. The population of Isle de Jean Charles is aging and dwindling, and if new people aren’t attracted to join the community, the town could shrivel away. But then, another problem: if too many people move in, the town’s makeup could become unrecognizable within a generation, defeating the project’s original purpose. (“How we structure entry into the community is an open question,” Sanders said.)

The most likely site for the new town is a sugar farm in the northern part of the same parish, Terrebonne Parish. The Evergreen property, as it’s called, was picked out of 16 potential sites and checks off the central wishes of the residents: It’s on higher land, it’s closer to a city than the old town but still rural, and it retains what Isle de Jean Charles residents value most about their home—peace and quiet.

At 600 acres, the space also has the potential to grow in the future. But at $19.1 million, the Evergreen property is not cheap, and buying it will eat up much of the total $48 million available for the project.

“It Still Feels Like Being Uprooted”

America’s cities were not built with climate resilience in mind. Much of our infrastructure runs in direct contradiction to climate-conscious transformations and adaptations. But just like San Francisco after the 1906 Great Earthquake, disaster has given city planners a clean slate, a blank canvas on which to create.

If the architects of the resettlement at OCD-DRU follow through with their plans, they’re going to build one of the most modern, climate-resilient cities in the country.

Some of the ideas are simply practical: Houses will be elevated to reflect future risks, not current flood expectations. But many of the proposals reflect a diversion from tradition city planning in coastal areas.

The town will “treat water as a resource rather than a problem,” the application asserts. Rain gardens, strategic tree planting, bioswales, and depressed community parks will reduce damage from flooding all while providing public value. Wetlands will be created to protect the community from storm surges, while preserving the region’s biodiversity and protecting vulnerable fisheries.

The envisioned community will be an example of environmentally forward thinking, with natural energy sources and cleaner water management. Solar power and a local grid system will keep the lights on even if the entire region looses power. The city’s design will encourage walking over driving.

The grandchildren of Rita Falgout, a lifelong resident of Isle de Jean Charles.

Michael Isaac Stein

Among American towns facing relocation, Isle de Jean Charles is relatively fortunate. It’s the only community to receive funding and institutional support from the government. Residents could be moving to one of the most resilient towns in Louisiana. Still, they feel far from lucky.

“For me, it’s not a celebration. It’s just not,” said Chris Brunet, whose family has been on the island for eight generations and whose grandfather was tribal chief. “We are for the relocation, but it still feels like being uprooted. We need to understand how much it requires of somebody to make that decision. That’s a process in itself, because we’re so attached to Isle de Jean Charles. This is home. This is where we belong.”

Relocation will always be traumatic. Even if there is government support and the promise of a shiny new town, coming to grips with the dissolution of your home comes with existential pain.

Verchick believes that while the government needs to be ready to aid communities that are forced to relocate, it also need to proactively help communities avoid that fate.

“As a country, the discussion jumps too quickly to relocation, and we don’t spend enough time on retrofitting or flood-proofing,” he said. “There’s plenty of stuff we can do in terms of planning to avoid mass destruction if we put the money up front and plan well.”

But there will still be towns for whom it’s too late. There will need to be a proper government apparatus to deal with this. And those involved in the Isle de Jean Charles relocation believe that the lessons they learn will be invaluable for a future administration that takes the threat of climate displacement seriously.

“My experience working a bunch of different disasters is that you get better every time,” said Forbes. “People following us will learn from all of this.”