Palm Beach Post/Zuma

This story was originally published by Slate and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

On Friday, former Puerto Rican Gov. Alejandro García Padilla tweeted a photo from inside a hospital, in which scrubbed-up doctors leaned over an operating table performing surgery lit only by a flashlight. “This is what POTUS calls a 10!” García Padilla wrote in the English version of his post. “Surgery performed with cellphones as flashlights in Puerto Rico today.”

The image quickly made the rounds on the internet; it currently has almost 9,000 retweets. That’s probably because this blurry picture feels like it’s worth a good deal more than 1,000 words. Closely cropped and the dictionary definition of “bleak,” it illuminates just a small sliver of the public health crisis Puerto Rico is currently facing.

This is what POTUS calls a 10! Surgery performed with cellphones as flashlights in Puerto Rico today. pic.twitter.com/5pnK5dkkE6

— Alejandro (@agarciapadilla) October 21, 2017

Some 33 days after Hurricane Maria made landfall on Puerto Rico, only 23 percent of residents have electricity, according to Status.pr, which provides daily updates on basic services on the island. While there are other, somewhat unrelated problems at play—gas stations have been slow to reopen, and roads are badly damaged—the power grid’s utter annihilation in the category 4 winds is not just a temporary inconvenience. A month later, the ways that lack of electricity can set off a cascade of other crises is becoming increasingly clear.

First, there’s the issue of clean water. Many wastewater disposal and clean water delivery systems are dependent on electricity. Without energy to power the systems, pumps don’t work, allowing sewage to build up on site instead of draining away to treatment plants. On the other end, drinking water cannot be delivered to residents without electricity either because those pumps and filters are also offline. Obviously, a lack of access to freshwater is a big problem— people are at risk of dehydration or, if they turn to lower-quality water sources, infection. In countries without modern plumbing and wastewater management, water-borne diseases such as leptospirosis thrive. But when a strong enough hurricane hits, even wealthy nations are at risk, as evidenced by the rivers of toxic waters stirred by Hurricane Harvey in Texas and Hurricane Irma in Florida.

Electricity is also crucial for communication. And clear communication is essential for relief and recovery efforts. Last month, I wrote for Slate that Puerto Rico was receiving short-term aid in the form of oil, water, and food delivery and that representatives of the territory were satisfied with initial relief efforts. But the past few weeks have shown that the recovery was too small in scale. Delivering supplies is irrelevant when people don’t know where or how to get them. On Friday, the Wall Street Journal wrote:

Gov. Ricardo Rosselló said that some of Puerto Rico’s 78 municipalities weren’t aware that food and water provided by FEMA were available at distribution centers—but that local officials needed to retrieve the supplies. Only when island and federal authorities were able to personally visit the towns could they relay vital information.

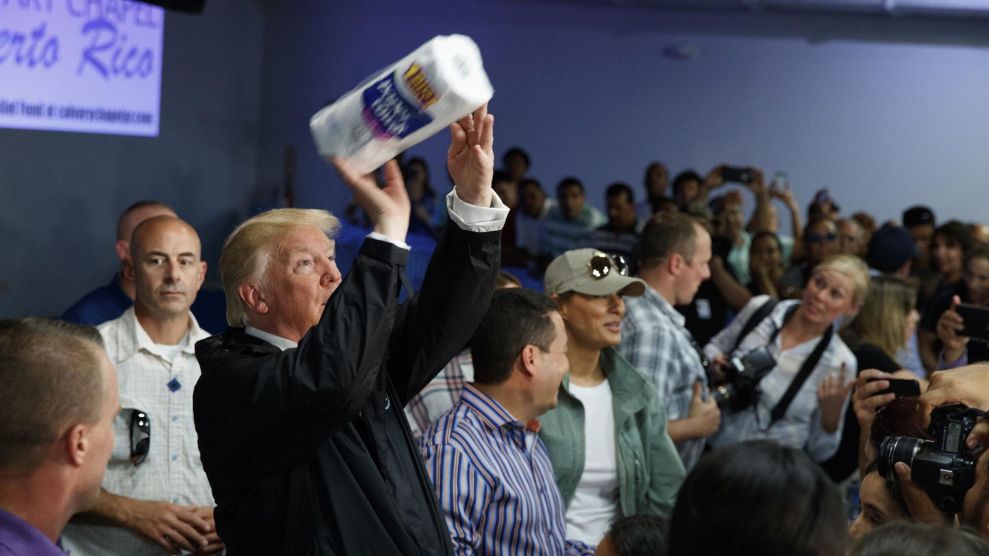

Even the relief efforts that have been attempted have likely provided little comfort to many residents—such little comfort, in fact, that they can come across almost as a mockery. A giant government-owned hospital ship, the USNS Comfort, arrived in Puerto Rico weeks ago to help out, but no one has figured out how to use it. The ship has extensive space and equipment for trauma care and a large staff, but CNN reported that as of Tuesday, only 33 of 250 beds were full. Many people don’t know about the ship (remember, without electricity, most cellphone towers are down). Even if they do, they can’t get to the port, as many of the island’s roads are impassable, doubly so without oil to power a car.

If this all sounds preposterous, it’s because it is. In the digital age, it’s difficult to imagine life-saving information like this being delivered Paul Revere–style, from one end of the island to the other. But until the electricity comes back through well-oiled generators or repaired electricity grids, the health of 3.4 million Puerto Ricans remains precarious and the vast potential of technology rendered moot. For now, cellphones will remain reduced to fancy flashlights, shining thin rays of light into a darkness that seemingly knows no end.