You don’t see self-driving cars taking over American cities yet, but robotic tractors already roar through our corn and soybean farms, helping to plant and spray crops. They also gather huge troves of data, measuring moisture levels in the soil and tracking unruly weeds. Combine that with customized weather forecasts and satellite imagery, and farmers can now make complex decisions like when to harvest—without ever stepping outside.

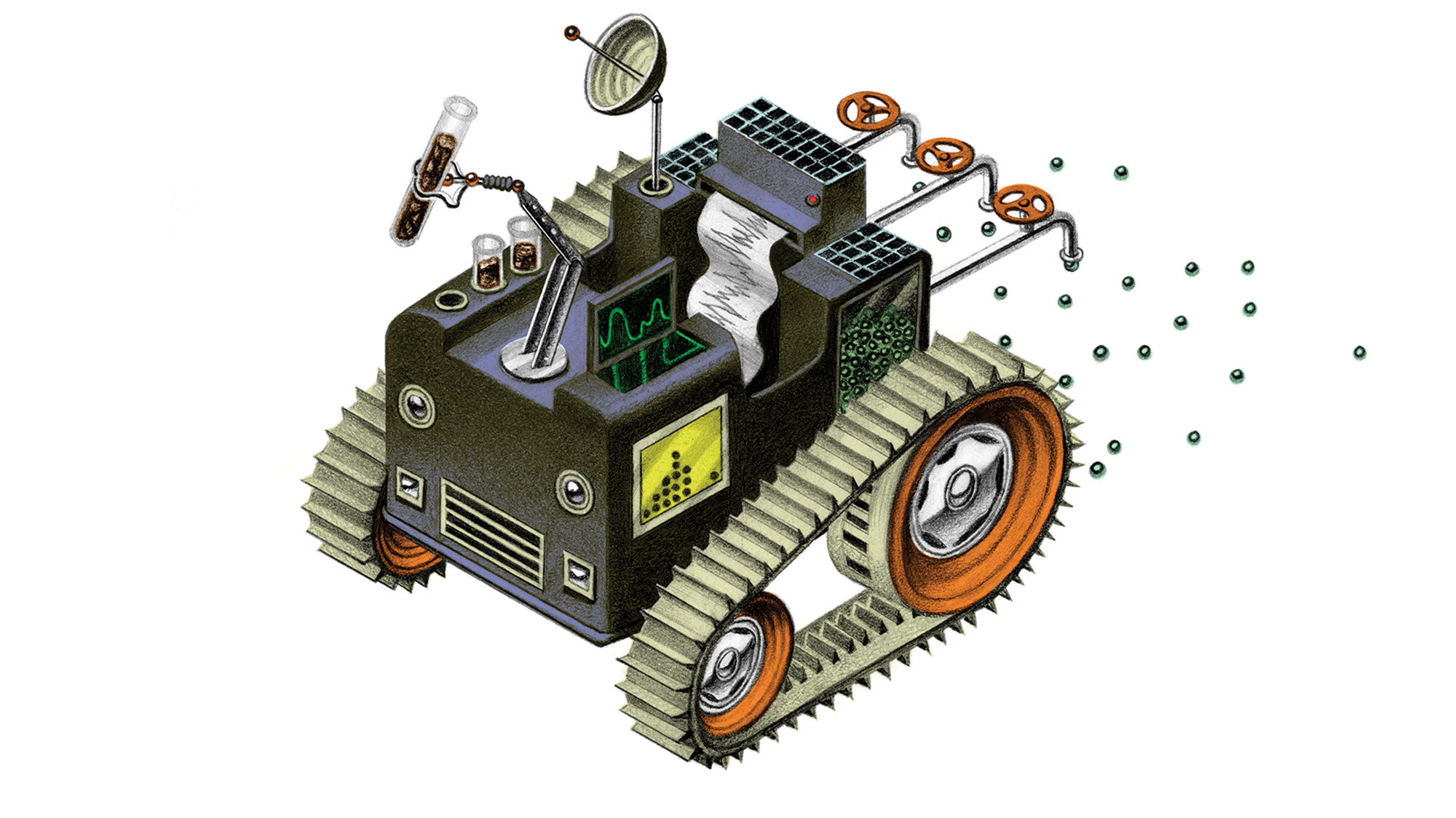

These tools are part of a new trend, known as “precision agriculture,” that is transforming how we grow crops. Using everything from sensors on combines to drones equipped with infrared cameras that monitor plant health, service providers—ranging from Monsanto and DuPont to startups—take data from the fields, upload it to the cloud, crunch it, and provide farmers with advice on how to run their operations.

Precision agriculture has been around since the ’90s, but it really took off when GPS technology became cheap and ubiquitous in the mid-2000s. It got another major boost in 2013, when Monsanto, a top producer of genetically modified seeds and pesticides, bought a Silicon Valley weather prediction startup called the Climate Corporation for $930 million. Monsanto now claims its digital-ag platform is used on nearly 45 percent of US corn and soybean acres. Even as seed and pesticide sales stagnate across the industry, revenue from farm data services reached $2.76 billion in 2015, and one market research firm estimates it’ll grow to $4.8 billion by 2020.

Last year, Monsanto cut a deal with John Deere, owner of most of the US tractor market. Data pulled from Deere tractors will feed the Climate Corp.’s data-crunching services. As a result of these collaborations, Monsanto CEO Hugh Grant recently told investors, Monsanto aims to become the “integrating hub” for seeds, traits, and pesticides, delivering “data insights” straight to farmers.

And now, of course, Monsanto is in the process of being bought by German chemical giant Bayer, itself a large purveyor of pesticides and (to a lesser extent) seeds. If the Monsanto-Bayer deal passes regulatory muster in the United States and the European Union, the combined company will own a quarter of the globe’s seed and pesticide markets. In the run-up to the deal, Bayer cited Monsanto’s heft in the data market as one of its main motivations for subsuming its smaller US rival.

Meanwhile, Bayer and Monsanto’s handful of competitors have jumped in. Dow and DuPont, also in the process of combining into one massive seed-and-agrichemical giant, have both launched precision-ag arms. Syngenta offers AgriEdge Excelsior, a “whole farm program…across digital platforms.” In short, these globe-spanning companies are vying to become one-stop farm shops, selling seeds (often genetically modified), pesticides, data analysis, and ultimately advice on how to knit it all together.

These massive corporations can be trusted to steer their data clients toward smart farming decisions…right? Matt Liebman, an agronomist at Iowa State University, is optimistic that on-farm tools can reduce the need for chemicals. Consider an independent Iowa-based company called AgSolver. Using data from a tractor’s GPS technology and harvest sensors, AgSolver’s software generates a precise map of the most productive parts of a farmer’s field and then overlays profit-and-loss information.

Some swaths of land produce so little that farmers spend more on seeds and chemicals than they’re making selling crops, Liebman says. By fallowing those particular areas, they can boost overall profits. And since such tracts often owe their paltry output to erosion, which leaches chemicals into groundwater through runoff, fallowing those fields could improve water quality. Liebman has also shown that adding a forage crop like clover or alfalfa to the typical corn-soybean rotation in the Midwest can drastically slash the need for herbicides to control weeds, and it can even improve overall yields.

Scott Marlow, executive director of farmer advocacy group Rural Advancement Foundation International, says it’s hard to imagine the Monsantos of the world nudging farmers toward systems that barely rely on chemicals. Many of the “yield-limiting” factors that the Climate Corp.’s services highlight can conveniently be addressed with pesticides its parent company sells, Marlow notes.

“Growers are pretty sharp,” says Michael Stern, a Monsanto vice president who leads the company’s Climate Corp. division. “We can provide a recommendation, but we also provide growers the ability to modify that recommendation.”

Sure, Marlow says, but the built-in bias does make a difference. He likens the situation to seeking financial advice from a Wall Street firm that profits from selling its own mutual funds. Farmers have to ask a question about the seed-and-chemical companies advising them: “How do I know if this is the best thing for me—or the best thing that makes them money?”