Chepko/iStock; robynmac/iStock; Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority

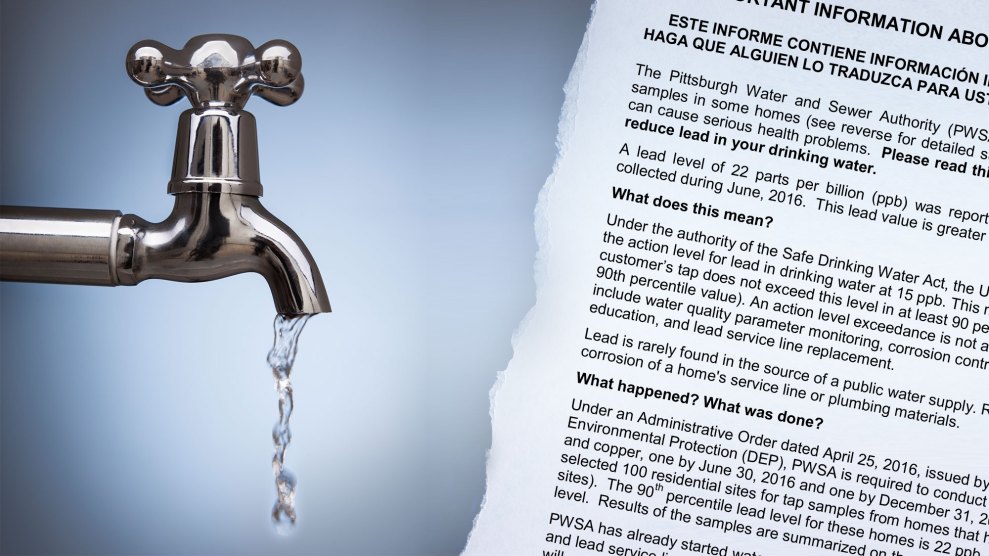

This summer, 81,000 homes in Pittsburgh received a worrisome letter about their water. The local utility “has found elevated levels of lead in tap water samples in some homes,” it said. Seventeen percent of samples had high levels of the metal, which can cause “serious health problems.”

The situation was bad enough to attract the attention of Marc Edwards, the Virginia Tech professor who helped expose the water crisis in Flint, Michigan. “The levels in Pittsburgh are comparable to those reported in Flint,” he said in an interview with local TV station WPXI.

This was surprising because until this year, Pittsburgh’s lead levels had always been normal. So what happened?

First, a bit of background: In 2012, the city faced a dilemma. Though it had clean water, its century-old water system desperately needed repair. And its utility, Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority, was plagued by administrative problems. Residents complained of bad customer service and unfair fees. After a series of poor financial decisions in the 2000s, PWSA was hundreds of millions of dollars in debt.

Pittsburgh isn’t alone: Public utilities around the country are trying to make ends meet with dwindling public funding and increasingly outdated infrastructure. Many, like Pittsburgh, turn to private management companies to help out.

Pittsburgh’s utility called in Veolia, a Paris-based company that consults with utilities, promising “customized, cost-effective solutions that reflect best practices, environmental protection and a better quality of life.” Veolia consults or manages water, waste, and energy systems in 530 cities in North America, with recent contracts in New York City, New Orleans, and Washington, DC. Last year, the company, which operates in 68 countries, brought in about $27 billion in revenue.

Pittsburgh hired Veolia to manage day-to-day operations and provide an interim executive team, helping the utility run more efficiently and save precious public dollars. Under the terms of the contract, Veolia would keep roughly half of every dollar the utility saved under its guidance.

Under the leadership of Jim Good, a Veolia executive serving as interim director, PWSA began making sweeping changes—and they seemed to be working: Within a year, call waiting times for concerned customers dropped by 50 percent. Thanks to new fees for commercial buildings, new customers, and other assorted changes, the utility saved $2 million.

According to a 2013 article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Veolia changed PWSA’s culture, too: Instead of traditional top-heavy management, Good checked in with employees over pizza and burgers every week. At a staff barbecue in 2012, “I told them that we were there to work with the employees as their partners,” he later told the Post-Gazette. “I provided assurances that there wouldn’t be any layoffs and that together we could achieve anything.”

But by the end of 2015, the utility had laid off or fired 23 people—including the safety and water quality managers, and the heads of finance and engineering, according to documents obtained through a Right-to-Know request. The PWSA laboratory staff, which was responsible for testing water quality throughout the 100,000-customer system, was cut in half. Stanley States, a water quality director with 36 years of experience at the utility (employees referred to him as “Dr. Water”) was transferred to an office-based job in the research department. Frustrated with the move, he retired.

Good maintains that not all staffing decisions were made by Veolia, which was in a consulting rather than management role when the layoffs occurred. Any suggested staffing changes had to be approved by the board, he said.

As the lab staff shrank, PWSA made major changes to its water treatment system. For decades, the city had been adding soda ash—a chemical similar to baking soda—to its water to prevent the pipes, many of which are lead, from corroding and leaching into the water. (Lack of corrosion controls caused lead to leach into the water in Flint.) In 2014, PWSA hastily replaced soda ash with another cheaper corrosion control treatment, caustic soda. Such a change typically requires a lengthy testing and authorization process with the state’s Department of Environmental Protection, but the DEP was never informed of the change. Nearly two years later, as news spread about the disaster in Flint, the utility switched back to soda ash.

Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Peduto puts the blame for the treatment change squarely on Veolia, saying the company never informed the utility’s board or the city. Veolia denies responsibility for the change, saying it “did not and would not prioritize cost savings ahead of effective corrosion control methods or water quality.”

What is certain is that this spring, the state’s DEP cited the utility for breaking state law and ordered immediate lead testing.

Tests this summer—the first since 2013—found that the city’s lead levels had crept up and, for the first time on record, exceed federal standards. Seventeen percent of homes had levels above the Environmental Protection Agency’s action level of 15 parts per billion.

Many suspect that the change in water treatment chemicals led to the jump in lead levels; the city is currently conducting an internal investigation into the matter.

Stanley States, the former water quality director, believes the staff cuts almost certainly played a role. Lead levels first crept up in 2013 because of a previous change in treatment chemicals, though they didn’t exceed federal standards. But without a fully staffed lab, says States, the matter wasn’t addressed. “They cut our laboratory in half,” he said. “We would have been researching like crazy this lead corrosion problem to see how to correct it.”

But Pittsburgh citizens’ complaints about Pittsburgh’s water goes beyond quality—it’s also extraordinarily expensive. In 2013, a year after Veolia was hired, the water board approved a 20 percent rate increase over four years; by 2017, the average residential water bill will be $50 per month—triple the average Midwest cost, according to the Guardian.

Soon after, customers began complaining that their bills were coming erratically and appeared to charge for water residents hadn’t used. One vacant property owner was charged for using 132,000 gallons of water in one month—that’s about how much a family of four uses in a year. “You don’t know if it’s going to come in, whether it’s late or not, how much it will be, a Pittsburgh retiree told Truthout. “Then you get it and there’s a late charge.”

In May of 2015, a group of Pittsburgh customers filed a class-action lawsuit against the utility, Veolia North America Water, and the accounting company keeping track of PWSA bills, alleging that new water meter readers installed in 2013 “catastrophically failed and customers have received grossly inaccurate and at times outrageously high bills”—including increases of nearly 600 percent. “PWSA is acutely aware that the billings are wrong but do not hesitate for a moment to issue ‘shut off’ notices and then arbitrarily turn off water service,” read the complaint. PWSA and Veolia declined to respond to the allegations.

Last December, facing the class-action lawsuit, a state citation for changing corrosion controls, and mounting debt, Pittsburgh terminated its contract with Veolia. All told, PWSA had paid Veolia $11 million over the course of the contract.

Earlier this month, the utility announced it was suing the company. According to a press release, Veolia “grossly mismanaged PWSA’s operations, abused its positions of special trust and confidence, and misled and deceived PWSA as part of its efforts to maximize profits for itself to the unfair detriment of PWSA and its customers.”

Pittsburgh isn’t the first municipality to sue Veolia this year. In April, Massachusetts officials sued Veolia, which was managing Plymouth’s sewage treatment facility, for allowing 10 million gallons of untreated sewage to spill in and around the town’s harbor last winter.

Two months later, Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette charged Veolia with fraud and negligence for failing to discover Flint’s enduring lead contamination problem after the city hired the company in 2015 to consult on water quality.

“Veolia stated that the water, quote, was safe,” Schuette told NPR. “Veolia also callously and fraudulently dismissed medical and health concerns by stating that, quote, some people may be sensitive to any water.”

In many cases, critics point to a pattern of Veolia saving utilities money through quick fixes—while ignoring bigger problems. In a phone interview, Kevin Acklin, the chief of staff for Pittsburgh’s Mayor Bill Peduto, pointed out that Veolia’s earnings are directly tied to the utility’s short-term savings. “They had the incentive under the contract to not make capital investments in property, planning, and equipment—to basically not fix the pipes when needed, to pass off those costs to other agencies, including the city and private homes,” he alleged. “Ultimately they were fiduciaries for the public authority, but they also served the business needs of a large multinational corporation.”

Veolia denies responsibility in both Plymouth and Flint, saying the leak in Plymouth came from a pipe failure that was out of its control, and that the contract in Flint was limited to looking at another chemical called TTHM.

In the case of Pittsburgh, Veolia maintains that PWSA’s board of directors retained control over the authority over the course of the three-year contract. “Veolia met its obligations and fulfilled the requirements of our contract in a fully transparent manner,” wrote a Veolia North America spokeswoman in an email. “We stand behind the work performed on behalf of PWSA.”

Yet Pittsburgh leaders can’t help but notice that the city’s utility is arguably even worse off than it was when it hired Veolia four years ago, with a depleted bank account—half of all earnings are directed to serving debt—and pipes that are still a century old. “The authority is in a pretty precarious financial situation right now, and I can’t sit here and point to anything tangible to show the positive legacy of the contract we had with Veolia,” says Acklin.

A former PWSA employee was more blunt about it. When asked how to advise utilities considering contracting with Veolia, he warned, “They will come in, rape your water company, and leave with money bags.”