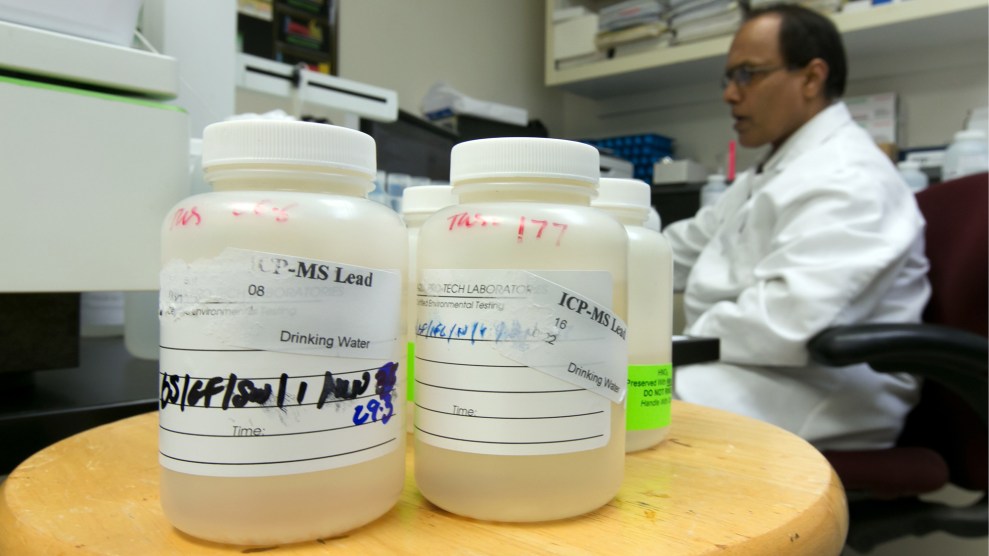

Water samples from Newark schools at Aqua Pro-Tech Laboratories.Richard Drew/AP

New York, home to more than 2.5 million public school students, may soon pass the nation’s first law requiring regular testing of water in those schools for the presence of lead. It likely won’t be the last: This year, at least 20 bills in seven states have been introduced to address lead contamination in school water, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

The bills reflect a testing frenzy: The water crisis in Flint, Michigan, led dozens of school districts, often at the behest of worried parents, to test water fountains and taps, children’s main sources of drinking water on school days. “No one was testing,” Robert Barrett, CEO of water testing firm Aqua Pro-Tech Laboratories, told the New York Times. “Now all of a sudden they’re all going crazy.”

Some results have been worrisome: In Newark, more than half of the city’s 67 schools had at least one fountain or sink whose water exceeded the Environmental Protection Agency’s threshold for lead contamination. This spring, dozens of schools—in Boston; Ithaca, New York; Portland, Oregon; Tacoma, Washington; and elsewhere—shut off their water after testing found lead in excess of the EPA “action level” of 15 parts per billion.

The contamination stems from a legal loophole the New York bill aims to close: The EPA requires schools to be connected to a local water source that is tested regularly for lead, but utilities are not required to test inside school facilities. The problem is that lead contamination in schools typically comes from pipes and fixtures within school buildings. Lead pipes were legal through the mid-1980s, and up until 2014, faucets and metal fixtures on water fountains and water coolers were allowed to contain up to 8 percent lead. The average American school building is 44 years old.

The New York bill, unanimously supported by the state Senate last month, is expected to be signed into law by Gov. Andrew Cuomo. It compels K-12 public schools to perform “periodic” lead tests at fountains and taps, and provides the funding to do so. If high lead levels are found, schools will be required to notify parents and provide “safe, potable” water for students until further tests show safe water. (The bill doesn’t cover universities or private and charter grade schools.) Bills in Michigan, New Jersey, North Carolina, and Rhode Island would also require regular testing. A new Ohio law requires utilities to map spots with a high likelihood of lead contamination and test them regularly. In Congress, Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) has introduced legislation that would require states to help schools test for lead, although it doesn’t provide funding.

The ultimate solution, researchers agree, is to replace all lead pipes and fixtures, but few school systems can afford such a project. A cheaper option is to install lead filters, which are effective so long as they are regularly maintained. The New York bill covers the cost of filters, as well as infrastructure fixes for fountains and taps that test at high levels. “While no legislation is perfect, at least the lead in school water problem will no longer be completely out of sight and out of mind,” says Marc Edwards, the Virginia Tech professor who helped expose the lead contamination crisis in Flint, Michigan.

But some experts fear that occasional water testing won’t be enough—and may even provide false assurances. This concern stems from what researchers call the “Russian Roulette” phenomenon. Lead particles come out of pipes and fixtures somewhat randomly, so a tap that tests clean one day might show high lead levels the next. Indeed, multiple tests from the same faucet often show very different results.

“As much as I applaud the intent, I do think that the specific policy [in New York] defies the science,” says Yanna Lambrinidou, a Virginia Tech scientist and president of Parents for Nontoxic Alternatives. “Testing seems to be happening quite rampantly right now, and it’s not a bad thing, but I think it needs to be done properly. The vast majority of buildings in this country have lead-bearing plumbing, and as long as there’s lead-bearing plumbing in a system, lead will leach into the water.”

How much lead is tolerable is also a matter of dispute. Most school districts rely on the EPA’s 15 ppb as a guide, but the American Association of Pediatrics recently released a statement noting that 15 ppb “is routinely (but erroneously) used as a health-based standard; it was not intended as a health-based standard, nor does it adequately protect children or pregnant women from adverse effects of lead exposure.” The association says water from drinking fountains should not exceed 1 part per billion. Indeed, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “no safe blood lead level in children has been identified.”