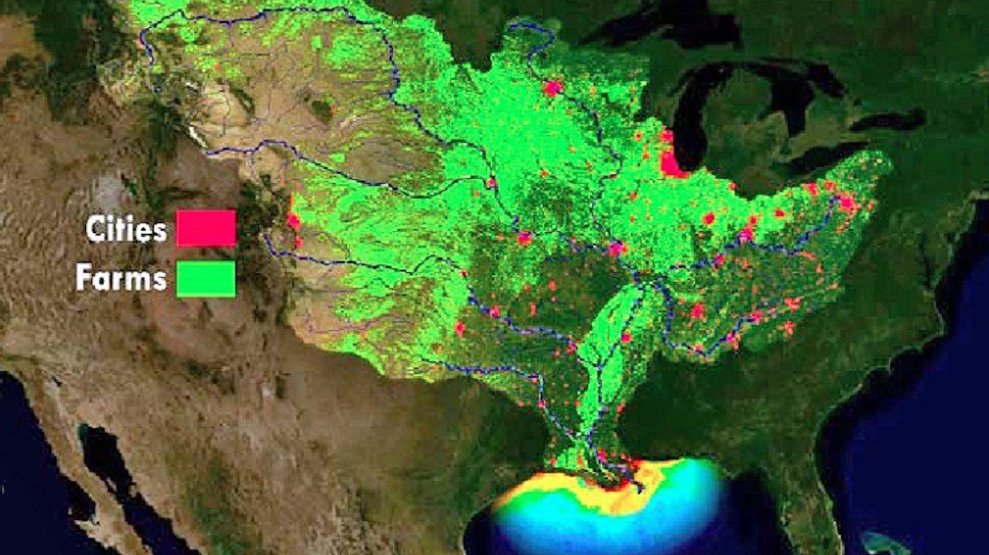

A NOAA vizualization of where the nitrogen comes from that fuels the annual dead zone. <a href="http://www.nnvl.noaa.gov/MediaDetail2.php?MediaID=1062&MediaTypeID=3&ResourceID=104616">NOAA</a>

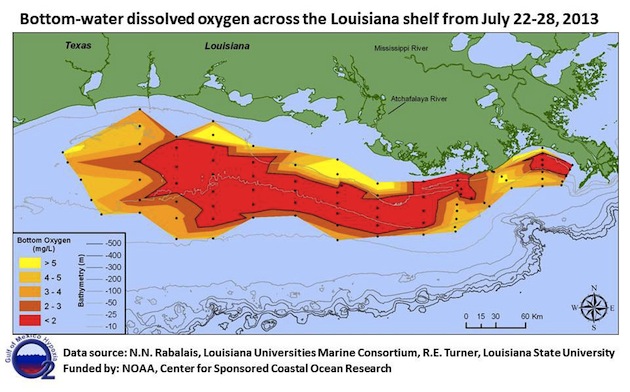

The Gulf of Mexico teems with biodiversity and contains some of the globe’s most productive fisheries. Yet starting in the early 1970s, large swaths of the Gulf began to experience annual dead zones in the late summer and early fall. This year’s will likely be nearly a third larger than normal, about the size of Connecticut, according to a recent report from the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium and Louisiana State University.

The problem is tied to industrial-scale meat production. To churn out huge amounts chicken, beef, and pork, the meat industry relies on corn as cheap feed. The US grows about a third of the globe’s corn, the great bulk of it in the Midwest, on land that drains into the Mississippi River. Every year, fertilizer runoff from Midwestern farms leaches into the Mississippi and makes its way to the Gulf of Mexico.

Intended to feed the nation’s vast corn crop, this renegade nitrogen instead feeds vast aquatic algae blooms in the early summer. When the algae blooms die and decay, they tie up oxygen from the water underneath. As a result, as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Organization puts it, “habitats that would normally be teeming with life become, essentially, biological deserts.”

Corn farmers typically plant freshly fertilized fields in April, leaving them prone to runoff from May storms. To predict the coming season’s dead zone, the Louisiana researchers looked at nitrogen loads coming into the Gulf in May, using NOAA data.

They’re expecting an unusually big one this year. And their report amounts to a de facto rebuke to the federal effort to address the problem: The Environmental Protection Agency’s Gulf Hypoxia Task Force, a largely voluntary effort to reduce fertilizer pollution in the Mississippi watershed. If this year’s dead zone turns out to be as large expected—about 6,800 square miles—it will be more than three times larger than EPA task force’s maximum target of around 2,000 square miles. As for the goal of reducing the amount of nitrogen streaming into the Gulf? “No progress has been made,” the Louisiana researchers bluntly stated.

Environmental Working Group’s Emily Cassidy adds:

The big river’s nitrogen concentration is nearing its highest level since 1997, when record-keeping began. According to the U.S. Geological Survey the river’s nitrogen concentrations have been above normal every month this year.

She also notes that fertilizer runoff does more than blot out sea life in this crucial and beleaguered ecosystem. It also fouls people’s drinking water in cities throughout the Midwest, including Des Moines, Columbus, and Toledo.