<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-211363525/stock-photo-young-businessman-resting-upon-money-on-a-white-background.html?src=z3dslyzT-xd20yNr2T4VUg-1-100">VGstockstudio</a>/Shutterstock

These are dark days for coal. In July, the industry hit a milestone when a major power company announced plans to shutter several coal-fired power plants in Iowa: More than 200 coal plants have been scheduled for closure since 2010, meaning nearly one-fifth of the US coal fleet is headed for retirement. President Barack Obama’s recently completed climate plan, which sets limits on carbon dioxide emissions from power plants, is designed to keep this trend going over the next decade. But the industry was in deep trouble even before Obama’s crackdown, thanks to the rock-bottom price of natural gas made possible by America’s fracking boom.

In case the shutdown of hundreds of coal plants wasn’t a sufficient indicator of the industry collapse, here’s another clue: coal companies’ rapidly deteriorating bottom lines.

A study this spring from the Carbon Tracker Institute found that over the past five years, coal producers have closed nearly 300 mines and lost 76 percent of their value. In August, Alpha Natural Resources, the country’s second-largest coal company, filed for bankruptcy, making it the biggest domino to fall in a string of more than two dozen corporate collapses during the past couple of years. On Monday, one of the company’s top executives resigned. Meanwhile, shares of Peabody Energy, the world’s biggest coal company, hit their lowest price ever, dipping below $1. A year ago, Peabody’s share price was hovering above $15; it peaked at $72 back in 2011. The stock plunge at Arch Coal was even more extreme—it fell from $3,600 to under $2 between 2011 and August 2015. (It has since rebounded slightly.) This year, both companies have been among the worst performers in the S&P 500.

You might think that the leaders of coal companies would be made to pay the price for these failures. But in the perverse world of American corporate compensation, they are, in fact, getting a raise.

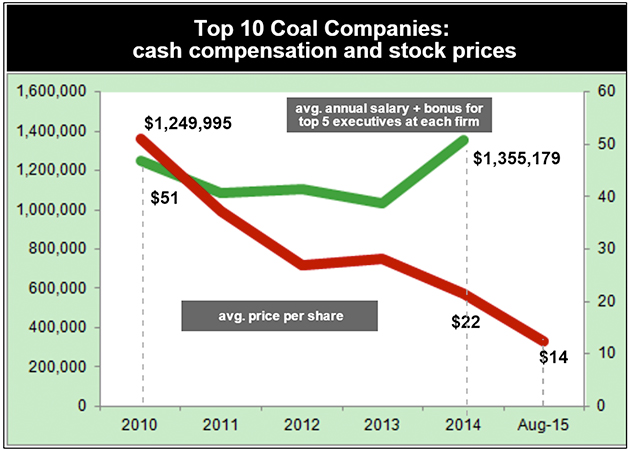

According to a report today from the Institute for Policy Studies, which bills itself as the country’s oldest progressive think tank, executive salaries and bonuses at the top 10 publicly traded coal companies increased an average of 8 percent between 2010 and 2014, even as the companies’ combined share price fell 58 percent. Meanwhile, the same executives cashed in well over $100 million in stock options, according to the report, which analyzed the companies’ public filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission. In other words, coal execs are cashing in while their companies tank.

“That [stock-based] part of their compensation package is not so valuable right now, so the value of their cash-based pay has been going up,” said Sarah Anderson, the report’s author. “We’re seeing this move to insulate them from the implosion of the coal sector by handing out more cash.”

The chart below, from the report, shows how cash compensation started to rise just as the share prices took their second dive in five years:

At Peabody, for example, CEO Greg Boyce cashed in $26 million in stock before the price collapse that began in 2011. At Arch Coal, cash compensation for the company’s top five executives grew 94 percent between 2010 and 2014, to an average of $2.3 million. Arch, Alpha, and Peabody did not return requests for comment.

To be clear, there’s no evidence of anything criminal happening here. But you can include this trend in the pantheon of corporate executives getting rewarded for their companies’ bad performance. Even the world’s best CEO probably wouldn’t be able to save these corporations—the fact is, the American coal market is disappearing and isn’t coming back. But, Anderson argues, if these execs were truly interested in fixing their business models, they could have invested in alternative forms of energy, such as gas or renewables. “The smart thing,” according to Anderson, “would have been to diversify their portfolio so they wouldn’t be so vulnerable.”