A storm lights up central California this summer. El Nino could bring more rain, but probably not enough to end the state's unprecedented drought.Marty Bicek/ZUMA

California could be in for a wetter-than-normal winter, thanks to the mysterious meteorological phenomenon known as El Niño. Weather scientists have been watching El Niño get stronger throughout this year and think it could match or surpass the strongest on record, back in 1997. What does this mean for long-suffering California and its interminable drought? Let us explain.

What the heck is El Niño again?

Normally, equatorial winds in the Pacific Ocean blow toward the west and push warm surface water in that direction. El Niño—”the child,” named in reference to Jesus by Spanish-speaking fishermen from South America who noticed, starting centuries ago, unusual weather around Christmas-time—happens every few years when those winds die down or diminish, leaving more warm water pooled along the equator off the coast of South America.

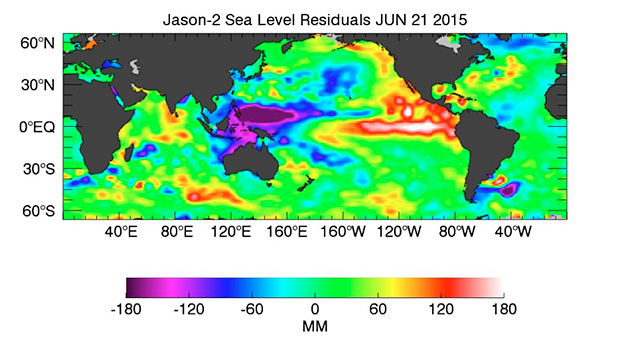

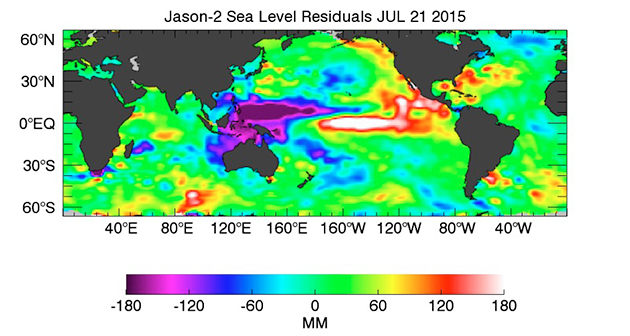

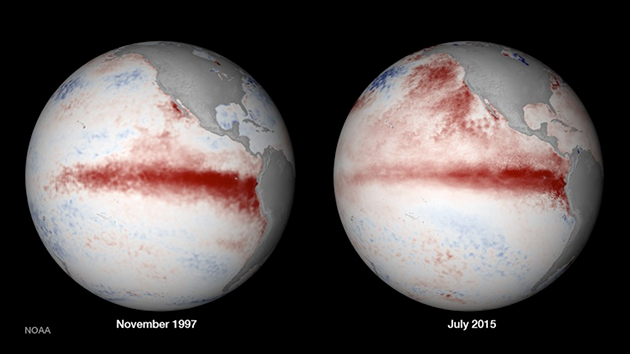

That’s been happening this year; the longer the wind pattern remains unusual, the more the eastern Pacific warms up. Here’s a map of ocean temperature anomalies (that is, variations from the long-term average) from late June. Notice the band of red and white (white is the hottest) in the center of the Pacific and the cooler-than-usual water off Southeast Asia? That’s El Niño:

(Side note: Satellite maps like these are a prime example of the kind of research GOP presidential contender Ted Cruz wants to block NASA from conducting.) Now check out the same reading from last week. It’s gotten stronger:

That trend is probably going to continue throughout this year, said Daniel Swain, an atmospheric scientist at Stanford University.

“It hasn’t peaked yet, and it’s already quite strong,” he said.

What happens then? These changes in water temperature cause changes in air temperature, and as a result the whole planet’s weather system gets a bit screwy. In some places, the end product is massive downpours—Peru is already anticipating devastating floods—while elsewhere, like India and Australia, El Niño means severe drought.

There are immediate economic impacts, as crops thrive in some places and fail in others. The 1997 El Niño caused a mild winter in the US that saved an estimated 850 lives and produced $19 billion in economic benefits, according to one study. But the same event caused floods that killed hundreds in South America. So whether El Niño is good or bad totally depends on where you live and is a bit of a crapshoot based on how the winds shift over the course of the summer.

Is climate change to blame for this year’s El Niño?

There’s no evidence of that so far, and in any case scientists are always wary about connecting any one specific event to the long-term trend of global warming. As to whether climate change will worsen El Niño in general, the verdict is still out, said NASA climatologist Bill Patzert.

“Nobody knows,” he said. “Some people say more El Niños, some people say less.” The main reason for that uncertainty, he said, is that climate models are generally not great at reproducing naturally-occuring, short-lived weather events like El Niño (as opposed to long-term, global patterns like a rise in temperatures, which models are quite reliable for). One recent study projected that while global warming was unlikely to change the overall frequency of El Niños, it could make the strongest ones more common.

On a related note, some climate change deniers like to attribute 20th-century increases in global temperature to El Niño, rather than man-made greenhouse gas emissions. This is bogus.

Will it save California from drought?

Here’s the short answer: Probably not.

“You creep into a drought slowly, and you creep out of it. There’s no quick fix,” Patzert said.

The signs are looking good for California to have a wetter-than-normal winter, as El Niño shifts atmospheric jet streams from the tropics northward, pushing stormy weather from Mexico and Central America onto the US West Coast. But there are a few major caveats:

1. That won’t happen until California’s normal rainy season, in mid-winter. So even if this El Niño stays strong, it won’t bring relief to drought-stricken communities for months to come.

2. There’s no guarantee that this El Niño will stay strong. “We’re in the waiting and finger-crossing mode,” Patzert said. “At this point I’m definitely hedging my bets against the Godzilla El Niño.” The equatorial winds could start to shift back to normal at any time, taking with them California’s prospects for a wet winter.

3. Whatever changes El Niño brings to California’s weather will have to contend with the weird atmospheric stuff that’s already at work keeping the drought in place. “This is the battle of the ‘blob’ and the El Niño,” Patzert said. Here’s what he means: This year a giant pool of warm water (dubbed “the blob”) is parked off the western US coast, which has supported a powerful high-pressure “ridge” in the atmosphere that keeps Pacific storms from moving onshore. The blob is major difference between this El Niño and the last major one:

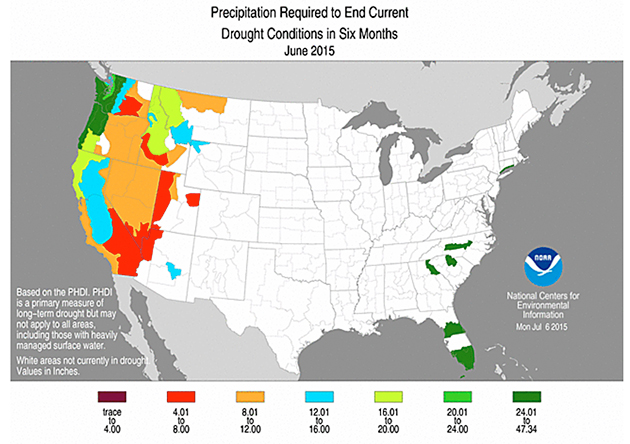

4. Finally, while a wet winter could bring some short-term relief, even the rainiest scenario won’t be enough to totally reverse California’s unprecedented, long-term drought just like that. According to NOAA, it would two feet or more of rainfall over the next six months to alleviate California’s drought conditions:

But, Patzert said, it will take an even more extended period of high rainfall to fully replenish the state’s depleted aquifers and provide relief that’s more permanent. At the same time, if winter temperatures remain as high as they were last year, any extra precipitation could fall as rain instead of snow, leaving the state without mountain snowpack to feed streams in the spring. And the kind of torrential rain associated with El Niño can also become deadly in a state where baked soil and higher-than normal wildfire activity are a recipe for disastrous mudslides.

“El Niño has been billed here as the great wet hope,” Patzert said. “But that belies the facts. El Niño usually just gives you a lot of flooding and mudslides, not drought relief.”