Four years ago, Michele Bachmann slammed Rick Perry—then the governor of Texas—for his executive order mandating HPV vaccinations. “I’m a mom of three children,” Bachmann said during a GOP presidential debate. “And to have innocent little 12-year-old girls be forced to have a government injection through an executive order is just flat out wrong.”

Bachmann, who at the time was a Republican congresswoman from Minnesota, expanded on her allegations the next day. “I will tell you that I had a mother last night come up to me here in Tampa, Fla., after the debate,” she said on the Today show. “She told me that her little daughter took that vaccine, that injection, and she suffered from mental retardation thereafter. It can have very dangerous side effects.” (Watch it above.)

Bachmann’s suggestion that the HPV vaccine is dangerous was completely false. “There is absolutely no scientific validity to this statement,” explained the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The 2016 campaign is just around the corner, and even though the Iowa caucuses are nearly a year away, we are already being inundated with dubious claims from potential candidates. Frequently, those claims touch upon issues related to science. Just in the past few weeks, we’ve heard Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) questioning vaccine safety, potential candidate Ben Carson suggesting immigration could be spreading disease, and Rep. Gary Palmer (R-Ala.) claiming that global temperature data had been “falsified.”

Enter Kathleen Hall Jamieson, the director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania, which operates the nonpartisan Factcheck.org. Founded in 2003, Factcheck was one of the first websites devoted to refuting misleading assertions about US politics. Last month, Factcheck launched Scicheck, a new project that evaluates the scientific claims made by politicians. In just a few weeks, Scicheck has countered inaccurate statements about issues ranging from climate change to the economic impact of the Human Genome Project.

On this weeks’ episode of the Inquiring Minds podcast, I asked Jamieson what inspired her organization to focus on scientific issues. She credits Bachmann.

“When Michele Bachmann in the last election made an allegation about the effects of…a vaccine, in public space on national television…the journalists in the real context didn’t know how to respond to the statement as clearly as they ought to,” explains Jamieson. “The time to contextualize is immediately. That should have been shot down immediately.”

So when the Stanton Foundation approached Factcheck to offer funding for a new initiative, the group decided that what it needed to do was hire “real science journalists” with the expertise to refute false claims and to get those corrections “into the bloodstream of journalism more quickly,” says Jamieson. “That’s how it happened. It’s thanks to Michele Bachmann.”

But Jamieson is keenly aware that it isn’t enough to simply rebut inaccurate claims in real time. One of the key challenges facing science communication is that voters frequently get their news from highly ideological media outlets that sometimes misrepresent the scientific consensus on controversial issues. This has contributed to substantial gaps between what the general public thinks and what scientists think on a wide range of issues, from evolution to the safety of genetically modified foods. To combat this problem, Jamieson recently proposed a new communication strategy called LIVA, an acronym that stands for leveraging scientific credibility (L), involving the audience (I), visualizing the data in a dynamic way (V), and creating relatable analogies for the reader (A). This method has shown promise in shifting people away from their partisan lens and helping them to better understand science. It even seems to work with one of the most polarizing scientific issues of all: climate change.

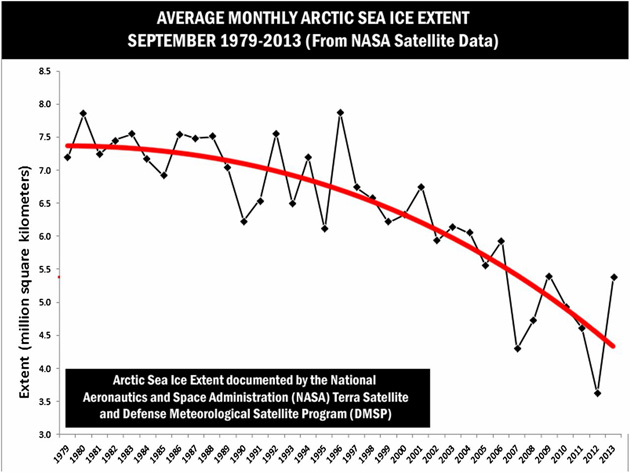

In Jamieson’s recent study, self-identified conservatives were shown a misleading article from Fox News with the headline “Arctic sea ice up 60 percent in 2013.” Part of this group was then shown additional information using the LIVA method, contextualizing the decades-long downward trend in sea ice and leveraging the credibility of NASA’s measurements. In the end, study participants who were subjected to the LIVA method were more likely to agree with the scientific consensus of a long-term decline in sea ice.

Jamieson is optimistic that these new science communication methods and sites like Scicheck will improve the overall political discourse. She has hired veteran science journalist Dave Levitan to lead this effort at Scicheck. And while it’s too early to tell if it will be successful, Levitan hopes that his work will make politicians “think more carefully when they talk about science.”

To listen to my entire interview with Kathleen Hall Jamieson, click below:

Inquiring Minds is a podcast hosted by neuroscientist and musician Indre Viskontas and Kishore Hari, the director of the Bay Area Science Festival. To catch future shows right when they are released, subscribe to Inquiring Minds via iTunes or RSS. You can follow the show on Twitter at @inquiringshow and like us on Facebook.