Geneticist Stephen Leslie kept coming back to a handful of data points that seemed out of place on his genetic map of Britain. “It was driving me absolutely insane,” he’s quoted as saying in Christine Kenneally’s new book, The Invisible History of the Human Race. No matter how many times he re-ran the analysis, double-checking the data and his code, the anomaly wouldn’t budge. So he figured that if his finding was true, there must be some logical explanation.

Some of the most important discoveries in science and technology have grown out of persistent and puzzling observations. Like when Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson discovered the first evidence of the Big Bang while mapping radio signals from the Milky Way. At first they thought it was interference from urban Manhattan, or maybe from pigeon poop. But eventually they realized that the annoying noise was in fact the signal that the beginning of the universe left behind: cosmic background radiation. And so they won the Nobel Prize. Or when Pfizer developed a little blue pill to treat chest pain, whose surprising side effect is responsible for much of the spam in your inbox.

In Leslie’s case, the anomaly was the finding that an individual living near the English city of Newcastle had eight great-grandparents who were all from the faraway county of Devon. On a recent episode of the Inquiring Minds podcast, Kenneally explained why this was so strange—and what it might tell us about the history of England.

When scientists are trying to figure out the genetic basis of a disease, they need to know what else differentiates people who have the illness from those who don’t. That way, they can tell which DNA variations might be related to the disease and which ones are entirely irrelevant to that disease. So if a particular genetic signature is associated with a specific population, that information can be help researchers rule out aspects of genetic variation that have nothing to do with the illness in question. Characterizing this regional genetic map is one of the main goals of Leslie’s work.

Kenneally’s book tracks the ways in which this sort of data can also be used to illuminate history, and she describes the methods that Leslie and his colleagues used to map out genetic variation in large populations. Specifically, the scientists collected and analyzed blood samples from a population of about 4,500 people living in rural Britain. To be a part of the study, participants had to have four grandparents who who were all born near each other. These blood samples were then entered into a genome-wide association analysis. That means that instead of looking for a handful of “candidate genes”—the way many genetic studies had done in the past, with little success—the scientists employed a new method that allowed them to simultaneously compare tens of thousands of sites on the genomes of thousands of people. Using this analysis, they were then able to identify parts of the genome that characterize people from specific places.

To learn more about this “People of the British Isles” study, you can watch this short video:

The research produced some remarkable results, revealing that groups of people from specific parts of Britain had unique genetic markers. “They isolated at least 20 different groups,” explains Kenneally. “And one of the first things that this tells us is that people lived in those areas for a very, very long time—way back to 1,000 or 2,000 years ago. The local villagers were marrying each other; their children grew up, they married the girl next door, the boy next door.” This fact was borne out by the rest of Leslie’s dataset: Most people in the study shared similar DNA with their closest neighbors.

It’s important to understand that the regional differences identified in the study were minor. “All these people [the entire sample, that is] are almost entirely, exactly genetically the same, and these differences are extremely subtle, and they probably have no impact whatsoever on people’s health or traits or anything like that,” says Kenneally. “But they’re these tastes or flavors in the genome that tell us a little bit about the past.”

So what was it that drove Leslie nuts as he stared at his data?

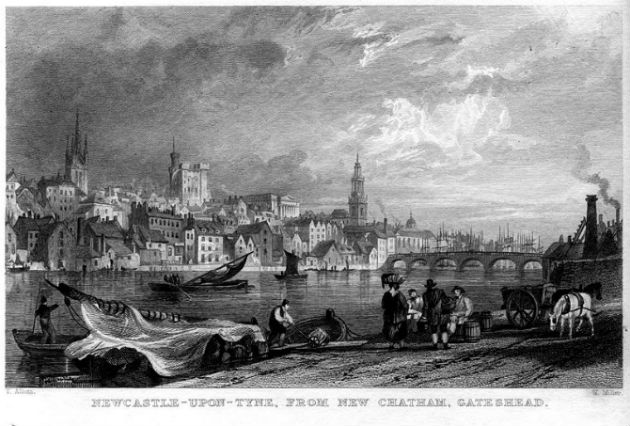

“Once they had sorted Great Britain out into all these neat little groups, there was someone in Newcastle who looked like they shouldn’t be there,” says Kenneally. This person was born near Newcastle and had four grandparents who were also born in the area. But the individual in question had DNA that looked a lot like the the patterns found in people who were from Devon, 400 miles to the south. Indeed, the genetic data seemed to suggest that back in the 1800s, all eight of this person’s great-grandparents had migrated to the region from the same part of Devon. For some reason, these people had all intermarried, and their descendants had too—instead of marrying the locals, as would be expected.

“This just seemed really implausible,” explains Kenneally. There wasn’t an obvious cultural reason why the ancestors of the migrants from Devon would remain so isolated, with even the next generation intermarrying rather than mixing with the locals. After all, they weren’t ethnically or religiously distinct from most other residents of Newcastle. “If they were a religious group—if they were Catholics, or if they were Jewish people—it might perhaps make sense that…they would have continued to marry within their group.” But there was nothing special about those Devonians. “No offense to Devonians; it’s just that there was nothing binding them together,” adds Kenneally. “So, Leslie ran and re-ran his analysis over and over again. It was absolutely driving him mad.”

When science failed to provide the solution to the puzzle, Leslie turned to the ultimate source of information: the internet. Searching genealogical websites, he found an important historic connection between Devon and Newcastle: In the 1800s, both places relied heavily on the mining industry. In 1830, Newcastle’s miners formed a union, and the following year, they went on strike. The Great Strike of 1831 was a massive victory for the miners. But a year later, the owners of the mine brought in workers from other parts of Britain, including Devon, and starved the locals into submission. The union soon collapsed, and the mine owners began to systematically lower wages. Other strikes would follow in the years to come. The situation left the locals angry and bitter—and much of that anger was no doubt directed at the out-of-town miners and their families.

“These people were strikebreakers,” says Kenneally. “So they would’ve been really isolated from their new communities. People would not have wanted to talk with them, let alone to marry them and have children with them.” And that’s one likely solution to Leslie’s genetic mystery: The eight transplants from Devon—along with their descendants—may have been ostracized by the locals.

Leslie’s analysis demonstrates just how powerful genetic data can be. “In these tiny gaps where we’re different, where you have a few markers here and there, or maybe a few hundred or thousand markers here and there,” says Kenneally, “those markers can tell us something about not just our health, not just our individual traits, but the history of the human race as well.”

Update: Our interview with Kenneally was the second in a three-part series focusing on DNA and what makes us human. You can click below to listen to this week’s show, in which Cynthia Graber interviews Donald Johanson about our evolutionary origins. Johanson was part of the team that discovered the fossil Lucy 40 years ago; at that time, Lucy was humans’ oldest ancestral remnant who walked upright.

Inquiring Minds is a podcast hosted by neuroscientist and musician Indre Viskontas. To catch future shows right when they are released, subscribe to Inquiring Minds via iTunes or RSS. We are also available on Stitcher. You can follow the show on Twitter at @inquiringshow and like us on Facebook. Inquiring Minds was also singled out as one of the “Best of 2013” on iTunes—you can learn more here.