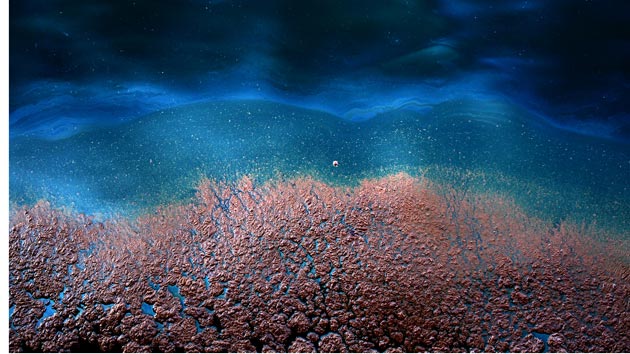

John Tesvich is a fourth-generation oyster farmer in Empire, a tiny Gulf Coast enclave south of New Orleans. He’s spent his life working in the rich oyster beds here, the most productive in the nation, and has weathered his share of storms: During Hurricane Katrina, his house ended up under 17 feet of water. But last week, as he navigated his 40-foot oyster boat out into open water, he admitted that the turmoil this region has faced in the last decade was beginning to wear him down.

“A lot has changed over the years,” he said. “It seems like one crisis after another sometimes.”

One crisis was particularly damaging to Tesvich’s industry: The 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill. The fourth anniversary of the busted undersea well’s sealing (after it gushed crude into the Gulf for nearly five months) is coming up next week, and Tesvich, who also chairs the oyster industry’s main statewide lobbying group, says his crop is still struggling to rebound.

Tesvich got some good news last week, when a federal judge in New Orleans found that BP’s “willful misconduct” and “gross negligence” had been the principle causes of the spill, a ruling that could eventually force BP to pay billions for ecological restoration in the Gulf. But for oystermen here, whose day-to-day income depends on these reefs, those dollars still seem very far away.

On the day last week when I visited, Tesvich piloted his boat, the “Croation Pride,” through a forest of white PVC stakes sticking up from the water that demarcate the boundaries of different oyster beds. There’s a complex network of ownership here, where individual oystermen lease sections of publicly-owned “waterbottom” on which to build artificial reefs and grow oysters. Many of these reefs are seeded with infant oysters harvested from nearby public reefs that act as a kind of village green—some small-scale oystermen depend entirely on the public reefs for their harvest, Tesvich says.

Since the spill, he says, “the availability of seed on the public reefs is almost nonexistant.”

The water in this delta, nestled between the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico, is warm and brackish, ideal for growing oysters. Immediately following the BP spill, that changed. State officials, desperate to keep the gushing oil from pushing upstream into highly sensitive estuaries, opened the flood gates on the river, unleashing a torrent of freshwater to push the oil back out to sea. The tactic largely worked, but at the cost of a whole season of oysters, which have limited tolerance for freshwater.

After the spill, Tesvich’s oyster beds were out of service for an entire year, as were those of many of his colleagues on the water. Freshwater incursions happen naturally sometimes when the river is running high; they’ve long been an obnoxious but survivable fact of life for oystermen here. In Tesvich’s experience, six months to a year is enough time for the oysters to bounce back.

But four years after the spill, “we haven’t seen that,” Tesvich says. “For some reason, reefs aren’t coming back.”

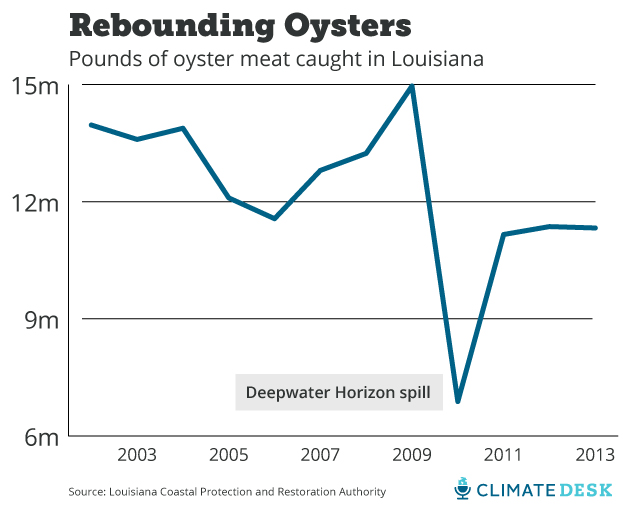

Official state data shows that while the statewide oyster harvest did rebound following the spill, it has since been roughly 23 percent lower on average than prior to the spill.

For its part, BP blames the oyster damage on the state of Louisiana’s freshwater diversion, a fact “those who attempt to pin blame on BP have utterly failed to recognize,” the company said in a statement.

Last year was Tesvich’s worst haul on record. This year has seen some improvement, but Tesvich’s harvest is still down over 30 percent from before the spill, with profits down 15-20 percent even though the smaller yield has doubled the price for a sack of oysters from $25 to $50 since 2010.

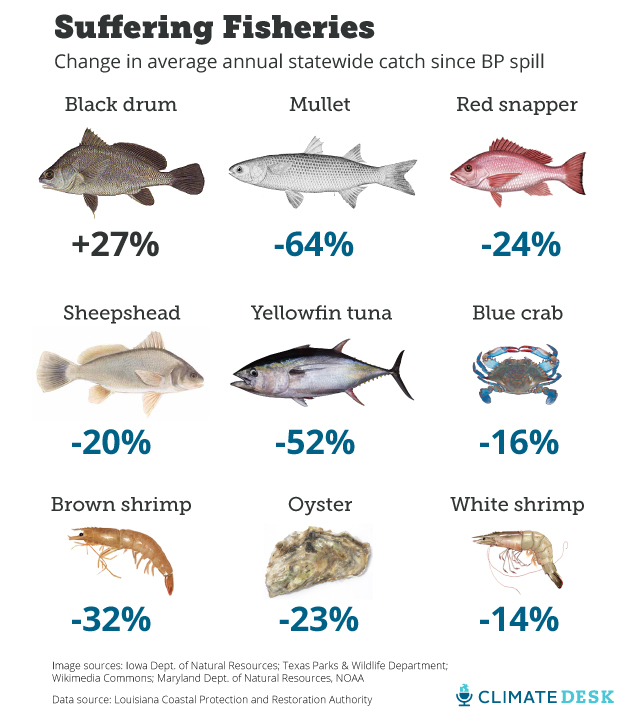

The catastrophe was not limited to oysters. With untold millions of barrels of oil spilled into the gulf (a federal court in New Orleans is set to rule on the exact volume in January), the ecological fallout was swift and severe, affecting everything from deep-water invertebrates at the foundation of the food chain to tuna to cetaceans (whales and dolphins). New evidence is emerging that links an ongoing, severe die-off in the gulf—more than 1,000 cetaceans have washed ashore dead since the event began in spring 2010, with scientists scrambling to understand why—to oil pollution.

In fact, eight out of nine commercial fisheries tracked by the state have lower annual average catches than prior to the spill*:

Justin Ehrenwerth, executive director of the federal council that is overseeing much of the BP recovery effort, said that after the tremendous damage done by the spill, fixing these natural systems is the first step to reviving the state’s economy.

“By restoring the ecosystem, you will see economic benefit,” he said.

One major cause of the recovery’s slow start, Ehrenwerth said, is that with BP’s Clean Water Act violation litigation still in court, very little money has yet been paid by the company for restoration projects. Last week’s ruling (which unfolded as I was standing on Tesvich’s oyster boat, no less), shed some light on the financial jump-start that could soon be headed to Empire.

After Judge Carl Barbier rules in January on the exact volume of oil spilled, he’ll assign a per-barrel fine corresponding to BP’s level of blame (which could range over $4,000), multiply by the number of barrels, and order BP to cough it up to Uncle Sam. Then, following guidelines established by the 2011 RESTORE Act, 80 percent of that money—about $18 billion, Ehrenwerth predicts—will be directed to Gulf restoration projects.

The ruling was “huge,” Tesvich said. “We want to see justice. They’re going to have to pay a lot more.”

But the court battle isn’t the only creaky bureaucratic wheel Tesvich is waiting on: Much of the basic science about the spill’s impact is locked up in the ongoing federal Natural Resource Damage Assessment, which is tasked with quantifying the spill’s exact environmental fallout. Without this information, it will be difficult for business owners like Tesvich to know exactly what happened and what to expect, and for financial resource managers like Ehrenwerth to know where to direct funds. That process could take up to another year to complete, said Natalie Peyronnin, director of Mississippi River science policy for the Environmental Defense Fund.

“There is a great scarcity of data,” she said. “The longer we wait, the more costly and difficult it’s going to be to restore these ecosystems.”

Meanwhile, Tesvich is trying to remain optimistic, a virtue he says is essential for oystermen these days. But that can be hard when he sees his catch. On the boat, his nephew Luke pulled a lever to haul up a giant basket from the sea bed. It was filled with mud, rocks, an odd shrimp, and about 15 marketable oysters. In the past, this bed would produce five times that number, Tesvich said.

“On a normal good year we have so much product we can’t even harvest all of it,” he said. Today, “I see a lot of uncertainty.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that all nine fisheries had lower annual average catches than prior to the spill. In fact, the black drum catch has increased. We regret the error.