Rupert Murdoch and David Koch, photographed shortly after speaking English to one anotherAP/PatrickMcMullan.com

Here in the United States, we fret a lot about global warming denial. Not only is it a dangerous delusion, it’s an incredibly prevalent one. Depending on your survey instrument of choice, we regularly learn that substantial minorities of Americans deny, or are skeptical of, the science of climate change.

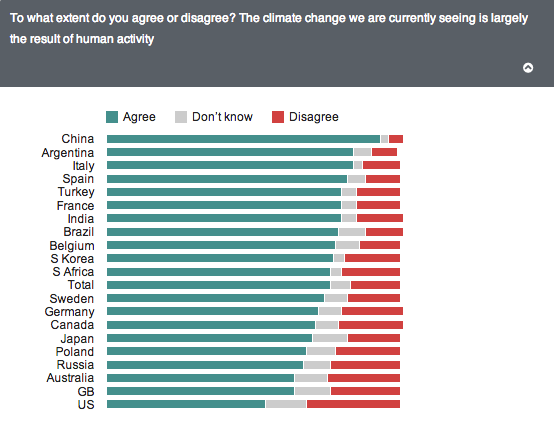

The global picture, however, is quite different. For instance, recently the UK-based market research firm Ipsos MORI released its “Global Trends 2014” report, which included a number of survey questions on the environment asked across 20 countries. (h/t Leo Hickman). And when it came to climate change, the result was very telling:

Note that these results are not perfectly comparable across countries, because the data were gathered online, and Ipsos MORI cautions that for developing countries like India and China, “the results should be viewed as representative of a more affluent and ‘connected’ population.”

Nonetheless, some pretty significant patterns are apparent. Perhaps most notably: Not only is the United States clearly the worst in its climate denial, but Great Britain and Australia are second and third worst, respectively. Canada, meanwhile, is the seventh worst.

What do these four nations have in common? They all speak the language of Shakespeare.

Why would that be? After all, presumably there is nothing about English, in and of itself, that predisposes you to climate change denial. Words and phrases like “doubt,” “natural causes,” “climate models,” and other skeptic mots are readily available in other languages. So what’s the real cause?

One possible answer is that it’s all about the political ideologies prevalent in these four countries.

“I do not find these results surprising,” says Riley Dunlap, a sociologist at Oklahoma State University who has extensively studied the climate denial movement. “It’s the countries where neo-liberalism is most hegemonic and with strong neo-liberal regimes (both in power and lurking on the sidelines to retake power) that have bred the most active denial campaigns—US, UK, Australia and now Canada. And the messages employed by these campaigns filter via the media and political elites to the public, especially the ideologically receptive portions.” (Neoliberalism is an economic philosophy centered on the importance of free markets and broadly opposed to big government interventions.)

Indeed, the English language media in three of these four countries are linked together by a single individual: Rupert Murdoch. An apparent climate skeptic or lukewarmer, Murdoch is the chairman of News Corp and 21st Century Fox. (You can watch him express his climate views here.) Some of the media outlets subsumed by the two conglomerates that he heads are responsible for quite a lot of English language climate skepticism and denial.

In the US, Fox News and the Wall Street Journal lead the way; research shows that Fox watching increases distrust of climate scientists. (You can also catch Fox News in Canada.) In Australia, a recent study found that slightly under a third of climate-related articles in 10 top Australian newspapers “did not accept” the scientific consensus on climate change, and that News Corp papers—the Australian, the Herald Sun, and the Daily Telegraph—were particular hotbeds of skepticism. “The Australian represents climate science as matter of opinion or debate rather than as a field for inquiry and investigation like all scientific fields,” noted the study.

And then there’s the UK. A 2010 academic study found that while News Corp outlets in this country from 1997 to 2007 did not produce as much strident climate skepticism as did their counterparts in the US and Australia, “the Sun newspaper offered a place for scornful skeptics on its opinion pages as did The Times and Sunday Times to a lesser extent.” (There are also other outlets in the UK, such as the Daily Mail, that feature plenty of skepticism but aren’t owned by News Corp.)

Thus, while there may not be anything inherent to the English language that impels climate denial, the fact that English language media are such a major source of that denial may in effect create a language barrier.

And media aren’t the only reason that denialist arguments are more readily available in the English language. There’s also the Anglophone nations’ concentration of climate “skeptic” think tanks, which provide the arguments and rationalizations necessary to feed this anti-science position. According to a study in Climatic Change earlier this year, the US is home to 91 different organizations (think tanks, advocacy groups, and trade associations) that collectively comprise a “climate change counter-movement.” The annual funding of these organizations, collectively, is “just over $900 million.” That is a truly massive amount of English-speaking climate “skeptic” activity, and while the study was limited to the US, it is hard to imagine that anything comparable exists in non-English speaking countries.

Ben Page, the chief executive of Ipsos MORI (which released the data) adds another possible causative factor behind the survey’s results, noting that environmental concern is very high in China today, due to the omnipresent conditions of environmental pollution. By contrast, that’s not a part of your everyday experience in England or Australia. “In many surveys in China, environment is the top concern,” Page comments. “In contrast, in the west, it’s a long way down the list behind the economy and crime.”

Whatever the precise concatenation of causes, the evidence seems clear. We English speakers have a special problem when it comes to understanding and accepting climate science. In language, we’re Anglophones; but in climate science, we’re a bunch of Anglophonies.