Some of the schoolgirls Boko Haram kidnapped in mid-April.AP

Blessing sits on the floor, knees into chest, in an empty room in Bukakotto village in eastern Nigeria. She’s “40 something,” but looks 25, and her face is scarred with tribal markings razor cut into her face as a baby. Just the day before, her sister was murdered. She went to her farm to look for firewood, Blessing says through a translator, and she was knifed to death by nomadic cattle herders with machetes. “They hacked her all over.”

A pink and white scarf hangs off Blessing’s head, and she arranges and rearranges it as she speaks, looking straight ahead into nothing. “We picked up her corpse and buried it yesterday.”

Blessing’s sister is another casualty in Nigeria’s long-running battle between mostly Christian farmers and mostly Muslim cattle herders over access to land. This increasingly violent clash is playing out alongside the Boko Haram terror campaign that has captivated the world since the group kidnapped more than 300 schoolgirls in April. On the surface, the two conflicts—which have both resulted in thousands of deaths over the past few years—appear unrelated. One is centered around Islamic fundamentalism, the other around grass and water. But look a bit further and you find that both conflicts are deeply tied to a massive ecological crisis that is breeding desperate poverty in the north of the country.

For centuries, the nomadic Fulani people drove their cattle east and west across the Sahel, the expanse of land just south of the Sahara desert. With the onset of a string of droughts in the early 20th century, Fulanis began to shift their migratory routes north to south. Land battles between nomadic Muslim cattle herders and Christian farmers were first reported about 60 years ago. The clashes have intensified since the start of another series of droughts beginning in the late 1960s that parched the land up north, driving more farmers and herders south for longer periods of time.

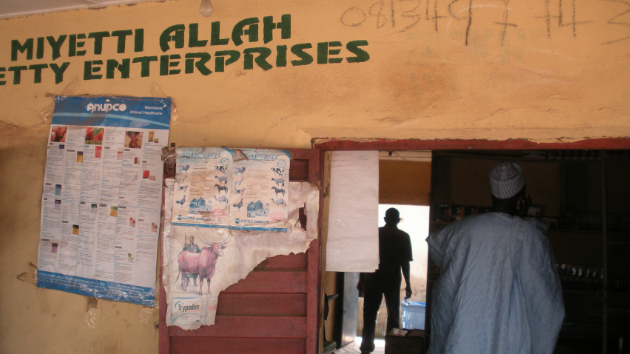

“They come [south] because of the nature of the climate in the north,” says Mohammed Husaini, a Fulani herdsman and official with Nigeria’s cattle breeder trade association. He’s seated on a plastic lawn chair inside his spartan cattle vitamin shop in the eastern Nigerian town of Garaku. Just outside the open front door, a young man chants the Koran into the afternoon heat.

“The period of time that northern Fulani nomads used to spend in the middle of the country used to be December to May,” he says. “Now it’s December to June or July, and some nomadic Fulanis decide to just stay here.” Why? Because, he explains, the grasses up north “don’t grow totally” any more.

Along with drought, Nigeria’s population explosion—about 125 million new people over the past half century—has overburdened the land and caused 136,000 square miles to turn to useless dust. Thirty-five percent of the land that was cultivatable in much of northern Nigeria 50 years ago is no longer arable.

And Lake Chad, which is perched along Nigeria’s northeasternmost edge, and whose waters once supported vast swathes of farming and grazing land, has lost more than 90 percent of its original size. Part of this shrinkage is due to recurrent droughts, though they have become less frequent in recent years. Just as important, humans have drained Lake Chad at an alarming rate; between 1983 and 1994, failed irrigation efforts were responsible for half of the decrease in the lake’s size.

Climate change has also contributed to the environmental changes in northern Nigeria, though it is not yet clear how much. Scientists are unsure, for example, how global warming has affected rainfall over the past few decades. What is clear is that the air over Nigeria has warmed by about 1.4 degrees Fahrenheit since the mid-20th century, and even more in the north of the country. Hotter temperatures mean that water is evaporating more quickly from Lake Chad, according to Chris Lennard, one of the lead authors of the most recent massive report from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)—though he says the effect of evaporation is relatively small compared to the devastation caused by droughts and irrigation.

The dying lake has collapsed the fishing industry and starved grazing lands and crops, displacing tens of thousands of Nigerians.

Hassan Garaba, a 24 year-old farmer and cattle herder who spends part of the year in the north of the country, calls the farmland up there “bakyau“—unfavorable. Three years ago, he harvested 30 bags of corn. This year, only 20. “The crops have been getting bad,” he says through a translator. “Some just died off.”

Over the past three years, the production of corn—which is largely grown in the north of the country—has fallen by 1.6 million metric tons, due to “unfavorable climactic conditions” and Boko Haram violence, according to the US Department of Agriculture. Yields of wheat, which is also mostly grown in the north, fell by 15,000 metric tons over the same time period.

The depleted northern soil has pushed both farmers and herders down south. According to Husaini, migration southward by Fulani nomads has increased roughly 50 percent in his region over the past few years. But, as the leader of one nearby farming community put it, “the land is not expanding.” Last year, competition for land led to the first clash between farmers and herders that Husaini’s community has ever seen. It lasted a month.

That was when 10 of Yakubu Mama’s uncles were slaughtered by farmers from the Eggon tribe. Mama, a 42 year-old Fulani herdsman, says through an interpreter that the Eggon militia knifed his relatives to death, “one by one.” And since the victims’ families were too afraid to go and collect the corpses, the bodies were eaten, Mama says, “by pigs and dogs.”

Husaini says about 200 Fulani herdsmen were killed along with Mama’s uncles during the January 2013 violence. There were heavy casualties on the Eggon side, too. Fighting between farmers and herders—which can also take on religious, ethnic, or political veneers—has killed a total of about 8,000 people since 2005, according to the International Crisis Group.

The farmer-herder conflict and the Boko Haram violence in the north are largely separate conflicts. But the two wars do intersect sometimes. After Boko Haram bombed churches and a marketplace in the city of Jos in December 2010, for example, the group said that the attack was revenge for recent Christian violence against Muslim Fulanis.

“Much of the conflict…between Christians and Muslims is about land and access to water,” says Vanda Felbab-Brown, an expert on insurgency at the Brookings Institution, “but Boko Haram is tapping to those sentiments and inflaming those sentiments.”

As Nigeria’s farmer-herder war heats up and more “young people are pushed to the wall,” there’s a greater chance that young Muslim Fulanis will be sucked into the growing Boko Haram insurgency, says Oluwakemi Okenyodo, the executive director of CLEEN Foundation, a Nigerian security-focused nonprofit.

Since its emergence in 2009, Boko Haram has slaughtered some 5,000 people. The terror organization, whose name loosely means “Western education is a sin,” staffs its ranks partly through a mosque and Islamic school set up in 2002 by Mohammed Yusuf, the group’s founder. But, as is the case with other insurgent movements around the world, economic hardship also helps drive recruitment. Poverty and unemployment in the north have reinforced the Boko Haram narrative that says the government has been corrupted by Western values, and thus cares more about enriching itself than helping Nigerians, according to a 2011 report by the congressionally-funded United States Institute For Peace.

The Nigerian government offers virtually no safety net to fishermen or cow herders or farmers who can no longer live on barren land. “Crop failure means starvation,” says Kwabena Gyimah-Brempong, a research fellow at the International Food Policy Research Institute in Abuja. More and more Nigerians are starving these days. In 2010, 61 percent of Nigerians lived in absolute poverty, defined as barely getting by on minimum levels of food, shelter, clothing. That’s up from 55 percent in 2004, according to the most recent poverty survey by the Nigerian statistics agency. It’s worse in northeastern Boko Haram country, where about 70 percent live in absolute poverty.

By some accounts, those who sign up for terrorism are motivated as much by economics as by the group’s Islamist rhetoric. In a previously unpublished interview with Human Rights Watch, the leader of the Civilian Joint Task Force, the anti-Boko Haram vigilante group made up partly of former Boko Haram members, said that Boko Haram recruitment “has nothing to do with religion, but a lot to do with economic resources.” The terror group “swoop[s] on those who don’t have any resources whatsoever,” says Mausi Segun, an HRW researcher based in northern Nigeria.

Which is why the Nigerian government has begun calling attention to links between environmental degradation, poverty, and violence. Labaran Maku, Nigeria’s Minister of Information, told Mother Jones that poverty due partly to crop failures in the north creates “a conducive environment for [terrorism] to prosper.” Eziuche Ubani, who chairs the committee on climate change in Nigeria’s House of Representatives, says that it has become “easy” for Boko Haram to recruit northern Nigerians “because people are already aggrieved and hopeless and depressed because they are losing their source of livelihood.”

The Nigerian military zeroes in on areas hit by agricultural collapse in its anti-Boko Haram raids. The security forces target fish markets in the northern city of Maiduguri, and Segun believes this is because Boko Haram recruits members from the impoverished fishing settlements around the disappearing Lake Chad.

Some Nigerian officials blame global warming for the environmental ravages stoking the north of the country. Last year, Nigeria’s national security adviser, Col. Sambo Dasuki, warned that climate change and desertification are tanking the economy in the northeast, and helping feed the terrorist insurgency there. Sen. Bukola Saraki, the chair of Nigeria’s senate committee on the environment, argues much the same.

Nigeria experts caution that while environmental destruction certainly contributes to poverty and violence in the north, there’s not enough hard evidence yet to implicate human-caused climate change in the bulk of the ecological disaster. Paul Lubeck, the associate director of African studies at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, says the Nigerian government may be overemphasizing the current effects of climate change on the Boko Haram insurgency to deflect blame for its own inability to stem attacks. “The north is faced with a crisis of unimaginable proportions,” he says, “and external solutions are very attractive.”

But in the coming decades, climate change will begin to take a greater toll across Africa, and violence will likely get worse.

Scientists don’t yet know exactly how climate change will affect rainfall in the Sahel—the region could even see more rain. But what is certain is that the area is going to get much warmer. Global temperatures are expected to rise by up to 8.4 degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the century if carbon emissions remain high. In the Sahel, the heat spike will be sharper.

Hotter temperatures will likely do serious damage across Africa to crops like wheat, rice, and corn, according to the IPCC, even if climate change ends up bringing heavier rainfall to the region. Wheat yields in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, could fall 35 percent by mid-century. Production of staple crops like sorghum could fall 15 percent by 2050; cassava production could drop by as much as 20 percent, according to the International Food Policy Research Institute.

If such a scenario pans out, “it would be bad,” says Jon Padgham, one of the authors of the IPCC report’s Africa section, especially “given that food security is already tenuous and population growth projections indicate that Africa will need to produce a lot more food to feed its growing population.”

The IPCC says that climate change could intensify resource conflicts and civil wars by aggravating poverty. The Pentagon has warned that it could increase violent extremism around the world. One recent study found that the frequency of violent conflict across the globe could rise by as much as 50 percent by 2050.

Though Nigerian officials have paid lip service to concerns about conflict linked to environmental collapse, terrorism experts say the government is not doing enough to prevent displaced farmers, herders, and fishermen in the northeast from turning to violence—with jobs or a smarter irrigation system or a safety net. The minister of agriculture has several plans to help out farmers, but most have not made it past discussion-group stage. Instead, Nigeria is mostly ignoring the farmer-herder conflict and is fighting Boko Haram with a largely unaccountable military—the government will spend roughly $6 billion this year on security forces whose expenditures are not tracked.

The United States also funds the Nigerian armed forces, to the tune of about $1 million per year, plus $3 million in law enforcement assistance. In May, President Obama sent about 80 US military personnel to Chad to aid in the recovery of the kidnapped Nigerian schoolgirls. But a more effective Boko Haram deterrent may be the millions the US State Department plans to spend next year on anti-poverty and agricultural development initiatives in the country aimed specifically at combating extremism.

Those programs won’t be enough, though, if the US and other rich countries don’t slam on the brakes on carbon emissions, and if Nigeria doesn’t do more for its poor. “If the US and Nigeria don’t partner to address climate change in the north, there will likely be repercussions for US interests in northern Nigeria,” says Jacob Zenn, an expert on radical groups in northern Nigeria at the Jamestown Foundation. “Possibly effects in the long-term so dire that one day they may be felt on the US home front.”

Reporting for this story was funded by a Middlebury College Fellowship in Environmental Journalism.